And death shall have no dominion.

Dead man naked they shall be one

With the man in the wind and the west moon;

When their bones are picked clean and the clean bones gone,

They shall have stars at elbow and foot;

Though they go mad they shall be sane,

Though they sink through the sea they shall rise again;

Though lovers be lost love shall not;

And death shall have no dominion.

-Dylan Thomas, excerpt from “And Death Shall Have No Dominion”

I enter to old books filling the room, undisturbed. As the door closes, the vicious whistling of the storm outside fades to a mere whisper tucked away somewhere behind the bookcases. Overhead, among the tops of the walls, wafts of smoke carry a yellowish light, glowing as a will-o’-wisp beckoning travelers searching the endless caches of books treasured and preserved throughout time. Winding my way through the piles and piles of books, a feeling of warmth and security draws me in further as its corridors seem to stretch out beyond the tiny room’s walls. The walls are no longer built of wood. They are built out of stories consisting of experiences from other times, from other worlds, and I find myself transported elsewhere. This is a safe haven.

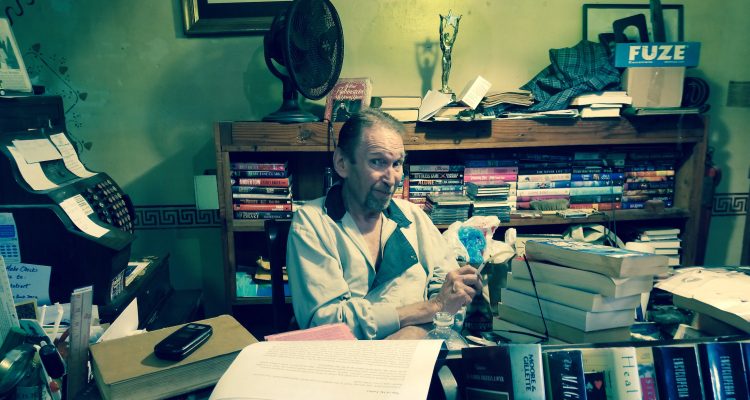

A green porcelain lamp hangs down from an arch, and sways back and forth above the shopkeeper’s head to the beat of the forgotten storm. Here, he sits behind his wooden desk, perplexed, as his eyes wander through his shop in a nostalgia mixed in melancholy, while the wavering light casts shadows and bits of light upon his face. After shuffling about in the little room that isn’t completely covered with books and loose papers, I discover the hard edges of a chair jutting up out of these amorphous collections before clearing a space to sit. With a cigarette perched between his two fingers, his eyes light up and he begins his story of love, adventure, and loss.

“I’m afraid books are going away. I hate computers. I very much believe that they are a form of anti-communication,” he laments as he looks at the books crowding his desk. Tom Stobart, the proprietor of The Paradox Book Store, has lived the life of a traveling bard. He takes pride in not owning a computer, and communicates when necessary via a very basic flip-phone. He prefers conversing in person because as an actor and playwright, he is not only invested into what people say, but he is tuned into how they say it, the speeches’ rhythms, and their tonalities. Here in the oldest book shop in the state of West Virginia, located in Wheeling’s historic Centre Market, he contemplates his future as he remembers his past.

The shop itself embodies so much of who he is. The sheer magnitude of books reflects his undying love for storytelling and learning. Returning back to the age of ten, he remembers journeying outward from Elm Grove into Wheeling atop the train tracks with his lifelong friend, Howard Monroe. These Saturday afternoon outings consisted of stopping by the soda fountain to grab a vanilla coke, eating some lunch, maybe catching a movie, and visiting the “Veteran’s Exchange,” which oddly sold World War II handicrafts and cheap, paperback books that were strewn across the shop in a haphazard fashion. In this shop, he lost his sense of time whilst digging through its troves of books, and reading everything he could get his hands on.

Tom’s fourth grade teacher, a woman by the name of Jane Fritz, further stoked the fire in his imagination. She was the kind of teacher who was content to simply sit back at her desk in silence if her students did not bring in interest or effort, but if they brought in genuine inquisitiveness and a bit of wonder, then she gave them the world. Tom did the latter – he entered class everyday with a surplus of questions pertaining to the latest book he read or about the world at large, and she happily did not hold back in answering. He cherishes her as the one who furthered his education and personal grown, but then his eyes trail off in elfin wonder, “Looking back, I’m not sure how I feel about the effectiveness of her methods for those who had no interest in the classroom.” Tom developed a very special relationship with her, where she mentored him even after he left his grade school days behind him. At age 14, Tom was about to embark upon a trip that would ignite an unceasing, lifelong love affair. In hopes that he would see the world, Jane graciously sent Tom on an all-expense paid trip to the bustling city of New York. In the front row in a Broadway theater, he watched Katharine Hepburn star in her only theatrical role as Coco Chanel in Coco. In sheer excitement after I noted that I was indeed familiar with Miss Hepburn, he throws up his hands as he conjures up the past. He brushes his cheek in its exact, unforgotten place, “Here. She kissed me right here.”

The door whips open, and once again, the incessant storm reminds us of its inescapable presence. Walking in wearing soggy clothing, a married couple prowls the shop’s collections. The wife searches for old cook books while the husband scavenges Tom’s array of vintage Playboy magazines, determined to find that specific Madonna issue. With an armful of recipes, she redirects her husband’s attention to the counter where Tom rings them up. The disappointed, hanged man trudges back off into the storm with his wife as Tom rings out, “Honey, the kids can eat tonight!” Looking down, he notices his extinguished cigarette. He lights up another and reenters his earlier train of thought.

The biography of the illustrious John Barrymore Good Night, Sweet Prince conspired in portraying New York City as a magical place where his imagination watched in continual awe. In it, the author Gene Fowler, a close friend of Barrymore, undertakes the task of portraying a man’s descent into New York’s night life as a tortured stage actor marked by passion and debauchery garbed in rich costume. Fascinated with this theatrical world, Tom packed his bags, and ran away with his adored girlfriend, Andrea, with nothing but mere change in their pockets. He chuckles, “New York is a horrible city to be poor in.” He worked at “The Strand”, a towering used book retailer in Greenwich Village, while she worked in a publishing house.

To this day, The Strand still dominates its corner in the village with its five floors offering used books in every subject imaginable. He remembers a particular time where he stood terrified in the elevator while making a delivery to the rare books room. It was an illuminated manuscript painstakingly handwritten by monks hundreds of years ago that stood a good two feet upright off the ground. In its exquisite construction, it contained a mere eight pages. After the workday ended, he always found himself with about twelve dollars in his pocket, and subsequently, a street hot dog for dinner. Money was tight, but that was part of the adventure.

The couple moved around frequently, trying to cut expenses while trying to achieve their dreams. They lived in Manhattan’s Upper West Side, which was much less affluent than today, where he remembers living in “fleabag hotels.” In fact, New York in the 1970s appeared as an eyesore, as news reporters warn the rest of America sitting safely in their suburban homes of gangs and drug violence. Apart from pricing books, Tom wrote, auditioned for stage productions, and frequented The White Horse Tavern, the bar in which the lyrical poet Dylan Thomas famously drank sixteen Irish whiskeys to his inevitable death. Echoing Dylan Thomas, Andrea’s parents disapproved of her marrying Tom, because he was only eighteen at the time. Dylan Thomas’s wife’s parents disapproved of his “Bohemian lifestyle,” and so, they too ran off in a sort of exile while continually struggling to support themselves.

The couple ate at a restaurant by the name of Tad’s Steakhouse. Tom’s mouth almost puckers as he shakes his head, “Terrible steaks, but they had all the beer, wine, and sangria you could drink for $3.95.” Sitting at a table, Tom and Andrea observed another couple leave their steak dinners unfinished, probably in fear of losing a crown from attempting to tear apart rubber masquerading as meat, and a pack of Marlboroughs. Turning his head to Andrea he asked, “Have you ever smoked a cigarette?” She shook her head no, “Have you?” Once again, the two or so feet between Tom and I morphs into a stage. He swiped the pack in quick movements, and they both took turns smoking their cigarettes. He bursts into laughter remembering his young self, “And I’ve been hooked ever since.”

“Hey, are you writing a book?” A man wearing thick Woody Allen glasses, one of Tom’s friends and a shop regular, appears on the outside of that wooden desk. “I went for a walk through the market, and you two are still talking. I should warn you, it won’t be a very interesting book,” he teases until his voice deepens into seriousness. He informs Tom of a mutual acquaintance’s escapades. The man frequented the book shop regularly where he would always buy one Playboy magazine, while his mind never left Vietnam. Tom’s friend speculates on what happened to the man; he heard that he got into a fight , and was later found and placed on a gurney. He stands for a bit enjoying the room’s dryness as he rocks back and forth on this heels, and jests once more to Tom and I before drumming up the courage to venture out into the inevitable.

Tom and Andrea continued to struggle in New York for a few months until the depletion of their funds brought them back home. Upon this homecoming, Andrea severed her relationship with Tom. While losing the girl with whom he was madly in love with, he was not lost. He remembers Wheeling as a city busting with activity, and here, his writing and acting career materialized where he helped found Towngate Theatre with Hal O’Leary. Beginning a play writing career spanning twenty years, Tom found himself sitting in the back of Bud’s Bar with papers strewn about a table listening in on every conversation. The late Bud’s Bar used to operate where Wheeling Brewing Company sits today. “There were two types of people who frequented Bud’s Bar: the Towngaters and Centre Wheeling passed out winos,” he says. Accompanied with a 60 cent shot of Jim Beam and a 30 cent draft, Tom couldn’t help but being inspired by those colorful characters wandering, or stumbling, into this smoky den of hoodlums. They would turn their heads around from the bar, look at each other in anxiety, and wonder, “Is he writing a movie about us? Do you think he’s listening to what we say?” Having spent some of his most productive times in this dive bar, he misses it dearly. He mourns, “You know, I’ve been back there to the brewing company a few times, but I stopped going. It makes me too sad.”

Tom opened up The Paradox Book Store at age 20 with a partner, where he dreamt of working on plays all day long on that overcrowded, wooden desk of his as he sold books to support himself. The very name of his shop stems back to his Towngate days. A smile cracks its way across Tom’s face, not unlike that of a Cheshire cat, “It’s a boring story, really,” before delving into another story. The Paradox Book Store derives its name from his first play entitled “The Paradox”, which in Tom’s words, was, “A very bad play.” O’Leary, who was the head of The Towngate Theatre at the time, was expecting a finished play from Tom to produce. Desperately needing a name to give to O’Leary, Tom christened his play “The Paradox” without having written a single line, or possessing a general concept of some sorts. Smoke billows into the air from his wavering cigarette, “It was set in a funeral home somewhere in D.C. It consisted of the assassination of a diplomat, and Nixon was mixed in there somewhere, waving his hands and chanting, ‘I’m not a crook’.”

Much of Tom’s writing was influenced by an Armenian American playwright by the name of William Saroyan. Famed for writing The Human Comedy, Saroyan focused on a sense of prevailing human goodness in the midst of dire circumstances. In fact, Tom mailed a copy of one of his treasured plays by Saroyan accompanied with his own original play, In Terminal Decline, to Saroyan himself, in hope of receiving it sent back to him autographed. Tom waited months with no reply, and after hearing rumors of Saroyan’s diminishing sanity, he had given up all hope. Tom shoots his arms up into the air as if he is addressing an audience seated within a packed theater, “And lo and behold! A package arrived on Christmas Eve with a letter that read, ‘From everybody’s best friend, William Saroyan’.” Saroyan sent back the copy of play autographed along with In Terminal Decline filled with notes of unabridged criticisms. Tom bursts into raucous laughter after recounting that Saroyan criticized his play as “base”.

Obsessed with studying characters myself, I inquired further into his methods for both writing an acting. For Tom, disciplining himself into the rhythm of writing on a consistent basis proves the most difficult. He commences his writing by jotting down the last line of a given play first, and then, he subsequently works his way to that point from the beginning. This forces him to adhere to a single, coherent narrative structure. “All of my plays are basically sad love stories,” he begins, but adds, “that part of my career is over. I’ve tried a few times, but nothing comes.” His play Ever After was produced in New York, Pittsburgh, and Los Angeles. Intended to be a simple two character act where every prop was pantomimed, the play failed to garner Tom’s approval. He traveled to all of the showings, and was disappointed to watch the actors utilizing physical props. He intended the play to take place in a coffee shop with a mere two chairs where everything else was painted black. He explains, “Black on stage brings it into the abstract where the imagination takes over. I’m naked, dress me.” In Tom’s eyes, not understanding his play’s stylistic choices rendered it inconsistent, and essentially killed it. However, the play did receive mixed national reviews ranging from ecstatic approval to hard-biting criticism. He remembers shooting down clamor of adapting it into a film, because like many writers, such as J. D. Salinger, he believed that the medium of film destroys a play’s integrity in shooting up into the ephemeral and abstract. Similarly, while touring with his play across country he did not wish to meddle in it as a director or lead actor. The playwright is too close to his own work, which is why the director must act as a midwife in conveying the work to the general audience.

Along with his extensive writing career, Tom has acted in over 200 plays. He begins, “I enjoyed playing old eccentric men,” his voice trails off, “But now, it’s not so enjoyable.” His three favorite roles he’s played are Edward P. Harvey from Harvey, in which his character is a perfectly amiable gentleman, but his best friend is a six-foot tall imaginary rabbit, Don Quixote, the disillusioned knight who famously went crazy while mistaking windmills for dragons, from the musical adaption Man of La Mancha, and the pickpocket king from Dickensian London Fagin in Oliver!. What I find interesting here is that none of these roles are heroes. They are all in their own ways lovable, pitiable, and complex. With all their given absurd eccentricities, they all possess specific grains of good human qualities that are twisted and distorted through circumstance. For example, Don Quixote drives himself to the brink of insanity from obsessing over cliched tales of knights and chivalry. Going deeper, the original novel satirizes the state of Spain’s economy at the time where it was driving itself into ruination from clinging onto old, feudal ways during the eve of progressive Enlightenment Period. So, here he is, Don Quioxte, in the upmost absurdist romantic glory, futilely battles an encroaching, modern world.

New York beckoned Tom back after being offered the role of John Quincy Adams, another odd old man, in the play Amistad, an original and new production Off-Broadway. During rehearsals, the rest of the cast became disgruntled with Tom, because he walked in dressed in full character, while they had only just received their scripts. They were so annoyed with Tom that the director took him aside and begged, “Can you look down and make it look like you’re reading the lines?” He explains to me, “I ask myself, ‘What is sympathetic? What is justifiable about the character I’m playing?'” It seems that Tom is fixated on these complex, unlikely characters because delving into them reveals a grand jewel that shines goodness even through failing faculties of the mind and body.

I can almost feel the wooden interior of the shop breathing from swelling and constricting in that humid rainstorm. An old friend of Tom’s, a silver haired Welshman famed for his piloting career, enters. The door remains open and I can hear the beating of the rain. He greets Tom in a very mild-mannered, calm tone. Tom’s face cannot conceal his sadness as he confesses his pressing health status. His friend does not waver, his facial expressions remain unaroused, and he stands here for a good moments time chatting about a rich range of topics and imparting a sense of hope into the room. The storm wanes, he bids us farewell, and departs. Tom then informs me that he does have plans to sell the shop at some point, but at the present time he does not have any prospective candidates. We talk for a few minutes longer joking and conversing before saying adieu. He smiles with his gaze fixed on no point in particular, and concludes, “This has been fun.”

Here he sits atop a wooden stool, his profile framed by old yellowing copies of literary classics, and savors another drag from his cigarette. And so:

No more may gulls cry at their ears

Or waves break loud on the seashores;

Where blew a flower may a flower no more

Lift its head to the blows of the rain;

Though they be mad and dead as nails,

Heads of the characters hammer through daisies;

Break in the sun till the sun breaks down,

And death shall have no dominion.

-Dylan Thomas, excerpt from “And Death Shall Have No Dominion”