When “Big League” Basketball Came to Town: The Short-Lived West Virginia Wheels

In 2009 and 2010, as a then-junior at Wheeling Jesuit University, I compiled quite a bit of research and interviews related to the brief history of the All-America Basketball Alliance of 1978. This is my attempt to produce a brief history of the AABA’s run, with an emphasis on Wheeling’s entry, the West Virginia Wheels. I hope that these efforts can be expanded in the future and contribute to the greater historiographies of minor league basketball and professional sports in Wheeling.

Introduction

Any minor league basketball fan knows the tortured history of the game. While minor league baseball and ice hockey have achieved some level of stability, basketball has struggled to achieve the same level of organization. One such casualty is the All-America Basketball Alliance, which played a small fraction of its 1978 season. The AABA never attracted the attention of basketball fans, and, owing to its brief life, failed to generate any nostalgia after its collapse.

The West Virginia Wheels were one of the eight entrants in the short-lived AABA. Unlike the Wheeling Blues of the 1940s, the Wheels did not generate a winning record and didn’t stick around long enough to become more than a footnote in Wheeling sports history.

With a mix of franchises in large cities like Indianapolis and Louisville, and smaller markets like Wheeling, the AABA tipped off in early January 1978 and folded quietly a month later. Based on an examination of local and national press coverage, coupled with interviews with former players and coaches, it is clear that the collapse of the AABA was brought about by a lethal combination of under-capitalized teams, poor attendance, and mother nature.

A New League

The AABA was announced in December 1977. In a UPI press release, the league cited the availability of talented basketball players, combined with a lack of available NBA roster space, as its reason for existence.

David Segal, a Philadelphia-based attorney, was listed as the founder and president of the league. Other league officials included Tom Ficara, who “originally conceived the idea for the league,” and Peter Schneider, a former administrator with the Philadelphia 76ers.

“The AABA has taken the best of these players and put them together with highly skilled professional coaches to give the eight league cities top flight basketball,” said league President David Segal. In this announcement, the league also made it clear that it did not intend to compete with the NBA, and would instead focus on smaller cities lacking a major league presence. Eight teams played in the 1978 AABA season, divided into northern and southern divisions:

Northern Division: Indiana (Indianapolis) Wizards, Kentucky (Louisville) Stallions, New York (White Plains) Guard, Rochester Zeniths

Southern Division: Carolina (Winston-Salem) Lightning, Georgia (Macon) Titans, Richmond Virginians, West Virginia (Wheeling) Wheels

Although the AABA had no intentions of competing with the NBA, at the time it appeared to be a superior option to other minor leagues. Players were promised a minimum salary of $9,600, along with a percentage of gate profits.

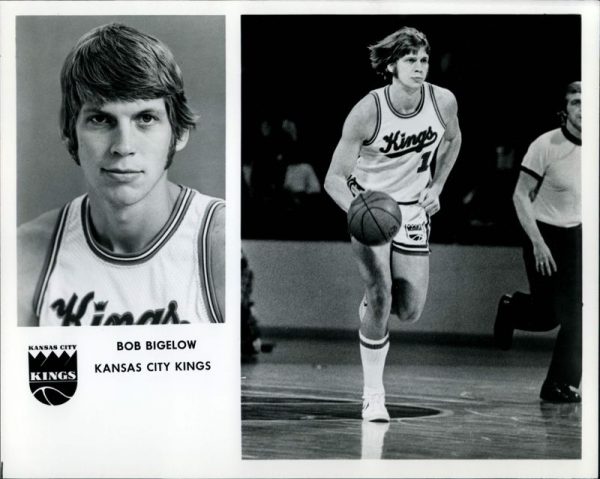

Bob Bigelow of the Carolina Lightning was one of the young basketball players to sign on with the AABA. At the time of the league’s announcement, Bigelow – a former first round draft pick of the Kansas City Kings – was playing in Quincy, MA with the Eastern Basketball Association’s Quincy Chiefs. According to Bigelow, the goal of every Eastern League player was to score enough points to get the attention of an NBA scout.

“[T]hat was crazy basketball – that was before three point shots, they were all like 140-135. Your worst sin was taking the ball out of bounds. You’d never get it back,” said Bigelow.

The promised stability, playing time, and high pay level were certainly attractive to basketball players at the time. According to Rochester Zeniths head coach Mauro Panaggio, “the AABA was a true professional team with the players holding no other jobs. On the other hand the EBA for years had been semi-professional. The players were paid on a per game basis while holding a full time outside job.”

Bigelow looked forward to guaranteed playing time.

[Lightning Head Coach Mike Dunleavy] said, because he knew I hadn’t played much with the Kings, ‘Bob, I can guarantee you 45 minutes a game.’ I said, ‘Mike, I’ll be on the first bus.’ I knew Mike wasn’t going to sit me. I would have killed him. So that was music to my ears, not that I wasn’t playing with the team here, I was playing plenty, but it sounded too good to be true.

In response to the AABA’s luring away talented EBA players, the venerable minor league threatened to sue. That lawsuit never came to fruition.

In Wheeling, the recently-built Wheeling Civic Center was already home to one basketball team – the Wheeling College (now Wheeling Jesuit University) Cardinals. According to Bill Van Horne of the Wheeling News-Register, the Cardinals and head coach Paul Baker were “turning basketball into an event” worthy of support. Van Horne was more skeptical of the Wheels.

What disturbs me about the league, which lists Wheeling as one of its franchise cities, is that decisions to place teams in various communities seem to have been based primarily upon whether such cities had arenas available with sufficient seating capacity and had dates open. There doesn’t appear to have been much, if any, research done to determine whether there would be even modest support for such a league in the proposed franchise city. […] The West Virginia Wheels may have their day but they are not something which we have been awaiting breathlessly.

Despite Van Horne’s skepticism, Wheeling had successfully hosted professional basketball in the past. The Wheeling Puritans played as an independent team in the 1947-48 season, and were succeeded by the Wheeling Blues, who played home games at Madison School on Wheeling Island.

The Wheels encountered early difficulties in securing ownership. Originally set to be owned by a Bedford Heights, OH businessman, the team was later taken over by the league. Local sports promoter Richard “PI” Drake was hired as general manager. On the day of the Wheels’ home opener, Bill Van Horne noted that the Wheels were “supposedly ‘owned’ by a Philadelphia lawyer who has never shown his face around town.”

Tip-Off

On January 6, 1978, the AABA tipped off in a double header at Louisville, Kentucky. Many AABA rosters were bolstered by the presence of former ABA and NBA players. The Indiana Wizards had the largest stable of former ABA stars. The team was coached by Indiana Pacers legend Freddie Lewis (who also played for the team) The roster included Roger Brown, Mel Daniels, Bob Netolicky – all former Pacers – along with Stew Johnson and Tom Washington.

Even the national sports media took notice of the presence of ex-ABA stars. Writing for The Sporting News, Jim O’Brien said, “[t]his is the American Basketball Association, or the ABA, all over again. What a good idea!” Writing about the Wizards, O’Brien noted, “ABA buffs might weep for joy if they read the roster of the Indiana Wizards.”

Although the Wizards roster would have made for a dominant team in 1972, by 1978 many of the Wizards were worn down from years of competition. Bob Bigelow recalled playing the Wizards in the league opener at Louisville Gardens.

[…]I remember playing Roger Brown and Mel Daniels from the old ABA Indiana team, and they were all like 30 pounds overweight. And I mean, Roger Brown was a terrific player. Not a Hall-of-Famer, but pretty close, and he and I were guarding each other. And as I said, he was at least five-seven years past his prime, so I just ran. He had to chase me around. I felt bad for the old man. But I tell you, when he and Mel Daniels were in shape, they were terrific players.

Other prominent AABA players included Ed Manning, Skip Brown, Jim Bradley, and Fly Williams, among others.

The Wheels likewise featured a mix of college and professional stars. The team was led by former ABA and NBA player Mike Barr. Unlike most coaches, Barr also played for the Wheels. A Duquesne University graduate, Barr was hired by the AABA to coach the Wheels after being released by the NBA’s Kansas City Kings. In an interview with Bill Van Horne, Barr noted that he “held off on other things” to accept the Wheels’ coaching position.

Other Wheels who either played for the Wheels or tried out were a mix of former NBA, ABA, and WVIAC players. Jerome Anderson – who would lead the Wheels in scoring – played collegiately for West Virginia University, and also played two seasons in the NBA. Another former NBA player, George Trapp, was signed by the Wheels but walked off the time before the start of the season due to a salary dispute.

Another big name signed by the Wheels was Archie Talley, a former Salem College (Salem International University) star. Talley, who averaged over 32 points per game during his time as a Salem Tiger, joined the Wheels after playing professionally overseas and for the Harlem Globetrotters. Bill Van Horne wrote that Talley was perhaps the Wheels’ best shot at attracting crowds, writing that “if there’s ever gonna be anyone who can lure the good citizenry of the Ohio Valley away from their television sets and into the Civic Center on a cold winter’s night, it could be the colorful, net-swishing Talley.”

In an interview, Talley said that he was contacted by Drake about playing for Wheels, whom he described as one of the “most charitable” people he knew.

“I didn’t know PI, but PI knew me, because in West Virginia people know who you are,” said Talley.

AABA players and coaches spoke highly of the league’s initial professionalism. Discussing the Wheeling Civic Center’s floor, Archie Talley noted, “it was so clean you could eat your dinner of the floor.” He added that the team was financially supported by the team’s GM, Drake, but he wasn’t sure if Drake had any ownership stake in the team. The Wheels also benefitted from the Civic Center’s installation of a $148,000 computerized scoreboard, the first of its kind in West Virginia. Its first use was for the Wheels’ January 1, 1978 home opener.

Other teams also were pleased with their support. According to Panaggio, “I think accommodations [provided on the road] were good and meals furnished were good also.”

The Wheels’ tipped off their season opener with a nail-biter of a game. Playing the Kentucky Stallions – another team with a stable of professional veterans – the Wheels were down by as many as 12 points before a furious rally saw them pull out a 109-107 win. Even the ever-skeptical Bill Van Horne noted that, “those of faint heart had better stay away” from the Stallions-Wheels re-match. The following night, in the aforementioned re-match, the Wheels lost 93-88 in front of 700 fans.

Struggles & Collapse

Despite talented athletes and a professional atmosphere, most AABA teams seem to have struggled with attendance. In the West Virginia Wheels’ home opener against Kentucky, the team only managed to draw 1,108 fans. Head coach Mike Barr put on a brave face in the Wheeling Intelligencer, noting that [t]hey’re the best crowd I’ve seen this year.” An article in the Winston-Salem Journal estimated attendance of just 100 in one Lightning home game. In contrast, the Rochester Zeniths attracted upwards of 5,000 fans to some games.

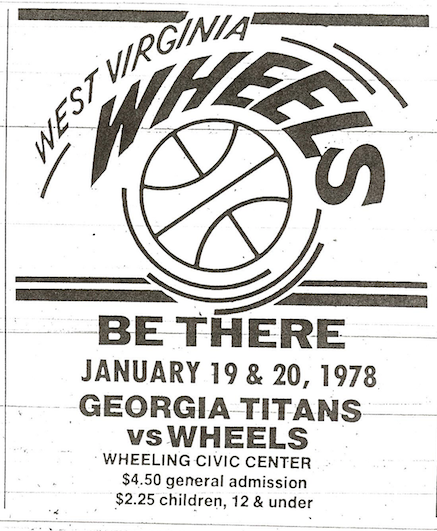

Another source of criticism was the AABA’s schedule, with nearly 70 games per team packed together tightly between January and May. Bill Van Horne described the schedule as “back-breaking” for the players and expensive for fans who might wish to see all of a team’s home stand. He wrote that “the schedule looks as though it were designed for a baseball team.” The winter start also contributed to travel issues. January 19 and 20, 1978 issues of the Wheeling News-Register noted that Wheels’ games against the Rochester Zeniths, Kentucky Stallions, and Georgia Titans were all postponed due to inclement weather.

These issues were acknowledged by league leadership. According to Jim O’Brien of The Sporting News, AABA president David Segal was “disappointed by the turnouts” and that weather was a source of attendance woes.

After the opening night double header in Louisville, the AABA began to run into funding issues. According to Panaggio, “[problems] began almost immediately after the successful opening double header in Kentucky. Most teams did not draw well and bills were left unpaid for visiting team expenses. All this time the Zeniths were doing well enough at the gate and paying their bills. It seemed like the Zeniths were the only franchise that was meeting their obligations. It later became a situation that Dick Hill was paying the expenses that permitted other games to be played. I don’t recall the exact situations but know this happened on at least one occasion.”

Ironically, in his interview with The Sporting News, Segal bragged that he was chosen as president of the AABA because he was “good with a calculator.”

Poor attendance, weather issues, and other financial issues spelled doom for the league. Scheduled Wheels home games against the Richmond Virginians were called off when the Virginians went on strike to protest lack of payment. Amazingly, the Wheeling News-Register noted that the Wheels’ crowds – less than 600 at most home games – were still second-best in the league, behind the Zeniths.

In the league’s final game on February 2, the Rochester Zeniths defeated the New York Guard 135-125. According to Panaggio, “in order to play the game the Zeniths owner, Dick Hill agreed to pay the expenses for the opponent to show for the game.” In the aftermath, the well-funded Zeniths went on to a successful run in the Continental Basketball Association.

By February 6, the AABA had collapsed. The Wheeling News-Register described a league office in disarray with limited communication to its teams. PI Drake, the Wheels’ General Manager, noted that he “spent over $30 in long-distance phones call and [couldn’t] get in touch with anyone but the secretary.” At their end of their run, the Wheels finished 3-8, tied for last in the league’s south division.”

Some AABA players took it better than others. According to Bigelow, the former Lightning player, “the good news is I was a first-round draft pick, so I was being paid guaranteed dollars by Kansas City even though they cut me. So I was making money. I got paid by the Kings for another four or five years […] So playing in Winston-Salem didn’t really bother me; if I got paid, so much the better, but if I wasn’t paid, okay, the Kansas City Kings were still paying me.”

In Wheeling, members of the now-defunct Wheels were stranded at the McLure House Hotel awaiting a paycheck and final word on the team’s future. In a February 8, 1878 column, Bill Van Horne excoriated the AABA brass for leaving PI Drake and Wheels players in such an unfortunate position, writing that

[There] is something tragic about the situation. The newly-organized league had raised hopes in the hearts of young men who aspired to professional basketball careers. For those who had been rejected or cast off by that exclusive fraternity of the young and the rich which is the NBA, this was a welcome opportunity.

Talley said that many of the AABA owners were “young millionaires” who were frightened by the league’s early operating losses.

“If they had hung in there, this would have been the best league ever.”

Talley’s recollections are at odds with Van Horne’s report on the league’s failure. While the league’s projections and promises contained the optimism of youthful millionaires, league co-founder Tom Ficara bragged to Van Horne at the Wheels’ home opener that the league did not contain any millionaires. Van Horne noted that the league probably could have used some millionaires, most of whom would be “smart enough not to invest in a minor league basketball franchise and go into business in the middle of winter.”

In particular, Van Horne expressed his regrets that he recommended PI Drake to the AABA, adding that “he had no office, no publication relations director, and limited powers.”

In his final report, Bill Van Horne warned David Segal “not to come back to this town and try to establish a team.”Incidentally, AABA co-founder Tom Ficara would later resurface in Wheeling as the owner of the proposed Wheeling Bulldogs. The Bulldogs were intended to be a team in the International Basketball Association (IBA) but never tipped off. After trying another proposed minor league, the National Alliance of Basketball Leagues, Ficara pulled out, stating, “I’m not interested in being somewhere that I am not welcome […] I was certainly having no fun at all.”

Conclusions

In 2010, sports promoter Don “Moose” Lews attempted to use the All-America Basketball Alliance name to launch an “all-white” basketball league. The league was rejected by the cities it targeted for franchises, and never tipped off. This league was not connected to the original AABA, but perhaps underscores the fact that the original AABA has completely receded from public awareness.

Although it was easy for the league to attractive talented athletes with promises generous compensation, attracting fans and managing a budget – all in the context of a brutal winter of 1978 – made the AABA unsustainable.

According to Archie Talley – who went on to become an assistant coach with the Charleston Gunners in the CBA – minor league teams must be able to attract sponsorship dollars in order to be viable. Talley noted that this was the problem for the Gunner as well as AABA teams. “You cannot survive just off people coming in,” said Talley. He added that he could only think of one minor league team – the LaCrosse Catbirds of the CBA – who were viable based on paid attendance alone.

The West Virginia Wheels only lasted 11 games and are barely a footnote in Wheeling sports history. However, they brought many talented athletes to Wheeling, christened the Wheeling Civic Center for professional sports, and made an impression on a young Archie Talley.

Talley noted that he enjoyed his time in Wheeling, saying, “I love Wheeling because Wheeling is a great place to be […] it was perfect.”

References are available upon request.