Susan and I arrived at our new home in Cove, Benin, in West Africa around the first of October 1987. We were driven the 100 kilometers from the de facto capital Cotonou by a Peace Corps truck with our belongings consisting of a small bag of western clothing (that would hold us until we could have some made), a kerosene refrigerator, a two-burner gas stove and a bottle of gas for the stove, a table and four chairs, a double bed with mosquito net and a kapok mattress. Our driver was Antoine, a Beninois who spoke French as well as his native Fongbe, which was the language of the tribe around Cotonou and southern Benin. A large crowd arrived to look at the foreigners (white people).

I was surprised, after intensive cross-cultural training, to be yelled at by our driver to drop something I had picked up to carry into the house. I was puzzled because the Peace Corps Beninois treated everyone with politeness and the utmost respect. He explained later that I was insulting all the kids’ parents who were there by my actions, as I was saying that the children were not raised properly. No adult carries anything when children are present.

A few minutes later I felt a light sliding touch on my arm. I looked and saw a little fellow, in his own world, feeling the hair on my arm, something he had never seen. This was my initiation into our village and our new home.

A few minutes later I felt a light sliding touch on my arm. I looked and saw a little fellow, in his own world, feeling the hair on my arm, something he had never seen. This was my initiation into our village and our new home.

Our landlord sent his oldest son, Ignace, who spoke fluent French and some English, to help us. He brought a woman named Sophie-non with him and introduced her to us. She would carry water from the well and keep the big clay jar at our house filled. It would provide all our water needs. Sophie-non, in turn, asked if her younger son could carry out our trash at no charge. We found out later that that was a real coup, as they used every bottle and can to store salt, sugar, etc. and all the cans were used to make toys. Old ballpoint pens with a nail and chicken feathers became lawn darts. What they didn’t use they sold or traded.

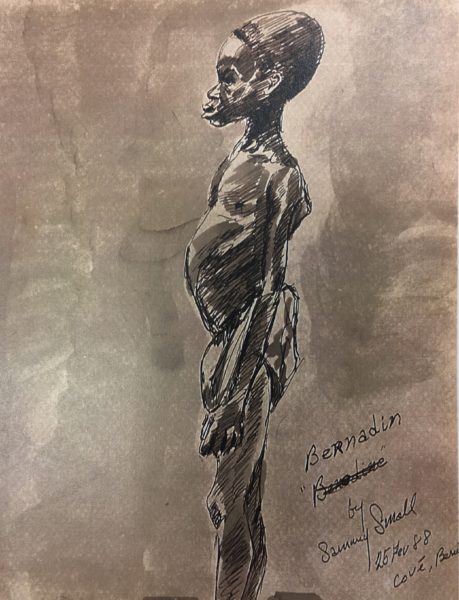

This is how Bernadin came into our lives. I had been trained to make mud stoves, foyer economique (economic fireplaces), so I asked him to be my helper.

The mud stoves were the best conservation idea I have ever seen. Everyone cooked in a pot held above the open fire by three stones. The mud stove simply encased the pot in a mud wall, with an opening to feed the firewood and oxygen. It concentrated the heat on the bottom of the pot, cutting cooking time in half (which was a huge hit with the women ) and reducing the amount of wood needed in half, saving the women countless hours and in the process, saving the wood of the forest. These mud stoves were a remarkable means to help avoid accidents with open fires and children.

It was a Sunday, and I was scheduled to rebuild the mud stoves at the German Hospital.

Susan, much better at French and Fongbe than I, asked Sophie-non to have Bernadin at our house to work with me on Thursday morning at eight (knowing it would be between eight-thirty and nine).

Bernadin was at our house every day at daylight. We then realized they had no clocks or calendars in their lives. They had their own system for dates and time.

Bernadin was “the man” when I took him for a lunch of beans and sauce in the square. He was so proud to be carrying the bucket with my tools and walking with me.

We became very close to Bernadin and his family, who lived in a group of mud huts not far from our place. Susan got in the habit of going to Sophie-non’s at dark and would sit with her and the children around an old bug spray can now filled with kerosene. The top had a right-side-up Coke bottle cap holding a braided cotton wick. It filled the tiny room with warm light on the red clay walls. Peanut shells covered the floor. They would talk and laugh at neither’s knowledge of each other’s language or just sit together in silence. This was always Susan’s most memorable flashback of human warmth and love.

I lucked into a good relationship with the family. I came home one day, and Susan told me that one of Sophie-non’s elders had died and that I should make “a call.” Someone would come and take me over, but more importantly, lead me back after dark. I arrived at the house where Gregorian Chants were being played throughout the neighborhood over a loudspeaker powered by a portable generator, a holdover from French Colonial days. The real music, the drums, was just beginning and would continue through the night. I was led into the hut where the grandfather was laid out on a bed. This was an important homage as people slept on a mat on the dirt floor. It appeared that every orifice was stuffed with kapok although the body was covered. The interior was lighted by the little can lamps of kerosene making the room quite smokey. The old folks were sitting on their haunches by the wall, wailing.

When I entered, all became quiet, and I became the center of attention; I knew I was expected to do something, so I walked to the bedside and recited in a reverent voice the Lord’s Prayer. After shaking hands with everyone and saying “Je suis desole,” which I mispronounced, and they couldn’t understand, I left. Sophie and her kin and Bernadin led me home. On the way back, I pointed to the sky covered with stars from horizon to horizon and said, “There was a new star tonight, which was their grandfather.”

I found out later I accidentally did all the right things. My prayer was interpreted as the white man’s good gris-gris (vou dou), and the star bit was right on the money with their belief system!

Susan was the real goodwill ambassador with her natural loving-people skills and language proficiency. Her French was really pretty good, and she also picked up a little Fongbe with which she truly communicated with the villagers. And as always, she made our home welcoming and warm to all comers. I remember when our dog died, she told me that Ignace asked her if she wanted a priest. The family all came by the night it happened to help bury Jessie.

Bernadin spent a lot of time at our house, and when I was ready to start selling the idea and building mud stoves, I asked him if he wanted to be my helper. I recall how proud he was to be working for a foreigner when we walked together, he carrying the bucket and the big coup-coup (machete). Age was not important to the Fon people so I would guess that he was 6 or 7. Bernadin was a real asset because he got us into many concessions (groups of mud houses). This was after we did all the stoves in the hospital “kitchen,” which was a lean-to that had many stoves to accommodate the various sizes of cooking pots. Family members had to provide all food for the patients. Bernadin enlisted his brother Hubert, who was a mason, to help us. This turned out to be a mixed blessing. He built the stoves with graceful lines and completed them with a satin smooth finish. They were so beautiful the women wanted to show them off and did not want to dirty them with a fire. We had to have a big meeting to decide how to “de-beautify” the stoves so they would be used.

Our mud stove building project was, I believe, a success. We got enough spread throughout the Cove area that their simple design and construction would be imitated throughout, helping to cut cooking time in half and cut the wood harvest in half.

Little Bernadin and I ate lunch in the Square every day we worked, enjoying beans and a rich sauce or gussi (goosy), which were deep-fried balls of hand-ground sesame seeds purchased from “Madam Gussi.” He became known as my buddy or, perhaps, my protege.

Our relationship with the family grew deeper as the months grew into years. Susan spent many evenings sitting around the fire while spending time with the family in their hut after dark. It is not necessary to converse in their culture but just to be with each other. It is said that the African comes alive after dark around their fire.

Sophie-non was not Bernadin’s mother’s name. When a woman gave birth to her first child, she took that child’s first name and added ‘non’ at the end, which meant ‘mother of.’ Her first born was Sophie. One day, Sophie-non wanted to talk with us about Bernadin. This was a very formal affair. Sophie-non arrived at our place at the appointed hour in her best clothing accompanied by Sophie, her interpreter. She told us that, after much family discussion, Sophie-non wanted us to take Bernadin when we returned to the United States.

Susan and I really hashed this over. She was all for it. I loved Bernadin as a son, I also loved Susan and was much older than she, by 21 years, and was afraid of passing out of the picture and leaving Susan with a youngster to raise by herself. We decided not.

“Life is what happens while you are making plans.”

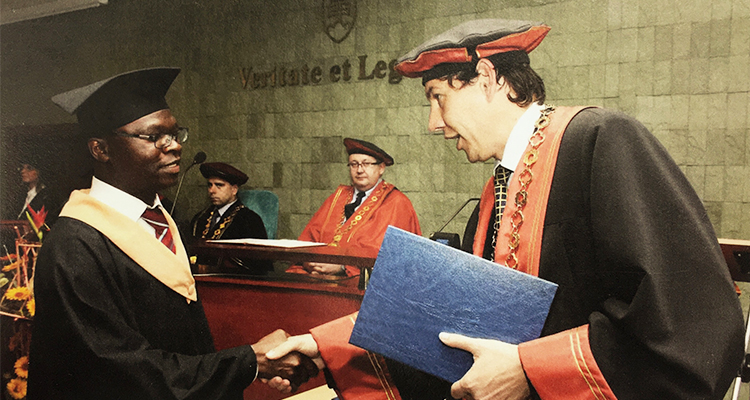

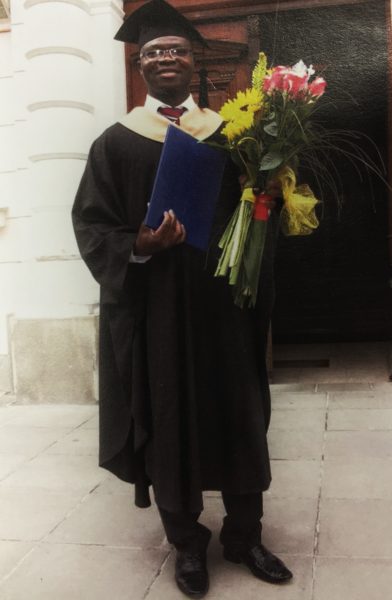

We returned home in 1990 after three and a half years as Peace Corps volunteers in Cove, Benin, and have kept in touch, mostly Christmas and holiday notes via the mail. More recently, Bernadin has caused me to learn Facebook. In addition to pictures he has sent to us of the awarding of his master’s degree from the University of Bratislava (where he is teaching), he has informed us that he will go to Versailles for part of this academic year and will complete work for his doctorate in 2018-19. Not bad for a child who grew up in a culture with an unwritten language and a numerical system that just went to 400. They could not imagine 400 of anything, much less more than that.

“Miracles occur unannounced, nothing happens by accident.”

• Bill Hogan, born and raised in Wheeling, W.Va., is a graduate of the University of Notre Dame and worked in the worlds of finance, real estate and alcoholism rehabilitation. Bill has six children and three grandchildren. He and his second wife, Susan Hogan, served in the U.S. Peace Corps from 1987-90 in Benin, West Africa. Now retired, he is a trustee of the Schenk Foundation, an artist, a writer and self-proclaimed “highly skilled dispenser of bull.”