It is one of the silent cities of the dead in Wheeling, but this one was split, and one half has been forgotten.

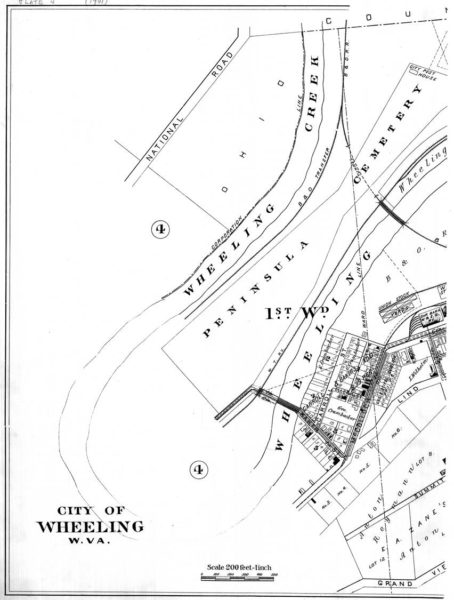

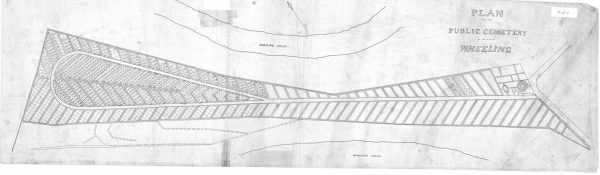

The Peninsula Cemetery, once the third largest in the state of West Virginia with more than 1,700 graves, was initially 22 acres in size until 1964. That is when more than 100 coffins were relocated to the Greenwood and Roney’s Point cemeteries to make way for Interstate 70 that runs from Baltimore to Cove Fort, Utah, and in some cases, those remains were moved twice because of the closures of the Hempfield and East Wheeling graveyards.

The Hempfield Cemetery, once located on the grounds where the Ohio County Public Library now stands, was removed to make way for the B&O Railroad, and the graves within the East Wheeling Cemetery were removed for neighborhood growth, according to local historian Jeanne Finstein.

“Oh, we cared about the people in those graves because the graves were moved,” she said. “As the city grew, there was a need for more land, so they did what they had to do at the time.

“Because the graves were moved, I think the argument can be made that our predecessors did care about those folks,” she said. “Otherwise, perhaps, they wouldn’t have been moved, but instead they could have just built on top of that.”

Records do exist and have been preserved by the city of Wheeling as well as Wheeling Heritage, but the majority of the municipality’s residents know very little about its history.

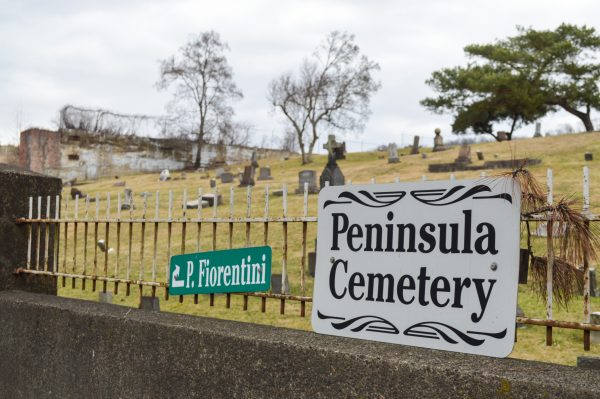

“Not too many people know very much about the Peninsula Cemetery, and maybe that’s because it’s pretty much out of the way,” said local historian Margaret Brennan. “But the same could have been said about the Mount Wood Cemetery until Rebekah Karelis from Wheeling Heritage brought attention to it. Not only did she shine a light on it, but she’s led the charge for all of the renovations that have taken place so far.

“There was a time when the Mount Wood Cemetery was considered forsaken because of the lack of maintenance and vandalism, and that caused some families to move bodies from there and to Greenwood,” she said. “

Karelis has collected an abundance of documents on local cemeteries, and she has learned that the Peninsula Cemetery was opened in 1842, 21 years before West Virginia became the country’s 35th state. Also discovered was the existence of the Pest House, a structure that was located near the top of Rock Point Road and housed local victims of smallpox during an epidemic in the 1890s.

“And it was one cemetery, not two like it is today, and I do have the original flat map that shows how the cemetery was laid out because the interstate separated the two,” she explained. “One of the reasons why some may believe that the Peninsula and Manchester cemeteries have always been two separate cemeteries is the age of many of the gravestones on the Manchester side. But those stones were not originally placed where they are today, and that’s because of the graves that have been moved during the course of the city’s history.”

The Road

I-70 was born in 1956 with the passage of the Federal Aid Highway Act, and construction workers carefully carved its 14-mile path through the Northern Panhandle in the 1960s and early 1970s. Hillsides were trimmed, homes vanished, and access ramps were created for Dallas Pike, Elm Grove, Pleasanton, Woodsdale, downtown and Wheeling Island before crossing into the state of Ohio.

But to reach Wheeling Tunnel, interments were exhumed, and the Peninsula Cemetery was chopped.

“Could you imagine having the contract to move all of those graves? Now, many years ago, I was told that the guys who worked that project would all hang out in this one bar, and I was told some of the stories that were told were just unbelievable,” Brennan said. “One of those stories involved those guys exhuming a body that was buried straight up and down. I just thought that was very strange when I heard that, but I guess that’s how some people wanted to be buried.

“These days I think moving graves would be a very interesting thing because you’d be dealing with the spirits and much more public opinion,” she said. “I think how we care for cemeteries says a lot about a community, and that’s why I think we would need to be very careful about it if it ever needed to happen again.”

At the top of the Peninsula Cemetery, fencing stops visitors from coming too close to I-70, but such a barrier does not exist on the Manchester land. It is close to this edge where Karelis found fallen gravestones that appear to be in a purposeful pile.

Were remains removed, but the workers left the stones behind?

No one knows for sure.

“It’s hard to say what graves were removed because of the records that were kept at the time” Karelis said. “There is a map of the section that was removed, but no one seems to know what remains were removed, and what still remains without the gravestones.

“We also know that the original entrance to the Peninsula Cemetery was not where it is today on Peninsula Street, but instead it was at the top of Rock Point Road on the Manchester side,” she explained. “But once the interstate went through in the 1960s, another entrance on the other side was obviously needed.”

Tales of hauntings within burial grounds are plentiful, and cemeteries in the Wheeling area are no exception. At the Peninsula Cemetery, one tale involved a woman in a black cape who, some say, stands over her gravesite.

“Now, I have always heard the same thing about the Greenwood Cemetery, so maybe that’s a tale that is consistent with the older cemeteries here in Wheeling,” Finstein said. “But, really, who knows?”

Karelis has heard tales about the Hempfield Tunnel, now known as Tunnel Green and a part of the Wheeling Heritage Trail system. Construction workers perished during the dig for the passageway, a murder reportedly took place within it, and railroad workers were killed when they failed to get out of the way of passing trains.

And a cemetery, of course, is located directly above it.

“I know there are stories about when the Hempfield Tunnel went through below the cemetery back in 1857,” Karelis said. “Of course, I do not know if they are just stories or if there is any truth to them, but it’s definitely part of the legend.

“But I don’t usually listen to ghost stories because I am not much of a fan of them,” she said with a laugh. “But some people do, and I am sure there are a lot of them out there.”

Resting in Peace?

One September in the late 1980s, the Peninsula Cemetery was vandalized to the tune of $42,000. Fencing was damaged, more than 70 tombstones were grounded, and the landscaping was violently disrupted, according to media archives at the Ohio County Public Library.

Meanwhile, the other side, the Manchester portion of the original grounds, was left disheveled and has since been ignored, and Finstein confirmed both plots of sacred land belong to the city of Wheeling.

“From what I understand about the Mount Wood Cemetery, and it could have been the case for the Peninsula Cemetery, that there was a cemetery association that had funds, at least for a while, to maintain the grounds,” Finstein said. “But obviously those funds ran out as the older the cemeteries grew, and then, it seems, the cemeteries were handed over to the city.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if the same thing took place with the Peninsula Cemetery, but if you go over to the other side to what is often referred to as the Manchester Cemetery, the opposite has taken place,” she continued. “There may be a sign, but it’s grown over, most of the stones are all on the ground, and not a lot of attention has been paid to it.”

Brennan has dared the rugged terrain where the original burials began, and she has chronicled information from the stones that can still be clearly read. “That area had people from the Civil War there, and also there were whole families. That’s why it’s just a shame that it’s in the condition it is in now.

“By the looks of it, it appears (city leaders) forgot that they own it,” Brennan said. “It’s grown over terribly right now and will get worse when spring arrives.”

Efforts to further preserve Mount Wood Cemetery will continue this year, but Karelis is not aware of an initiative to solve the mysteries of the Peninsula Cemetery or to beautify the Manchester grounds.

“That is something I have wondered about in the past, and on the city’s website, it does not list the Manchester half as a cemetery the city owns,” Karelis reported. “It is city property, though, but I guess it’s because it’s so old so not a lot of people are visiting those grave sites so no one complains.”

(Photos by Steve Novotney)