By Gerry Griffith

Weelunk Contibutor

Wheeling Couple’s Bloody Crime Spree Keeps the Minns Confectionary Crew Buzzing

When Tom Minns walked into his little store in South Wheeling on a rainy afternoon in 1930 with a huge bundle of Wheeling newspapers on his shoulder, the crowd of loafers surrounded him anxious to get the latest news about the spectacular crime spree that had held much of the nation spellbound over the past few weeks.

“Easy kids, easy,” Tom said as he waded through the young people to the counter where he took out an old worn pocket knife and cut the cords that held the papers together.

“Leave your change on the counter, kids. You know how it’s done.”

One by one, the young men and women picked up their copy of the paper and plunked down a coin on Tom’s candy counter.

The loafers, like thousands of others in a wide swath of the country’s midsection, were fascinated by the newspaper stories they were reading and discussing that detailed the multi-state crime spree and ultimate violent end of a man and woman who robbed small businesses and gunned down police without a second thought. It wasn’t just the magnitude of the crimes and the callousness with which they were committed that held their fascination; it was the fact that the perpetrators were from Wheeling. They may have even been occasional customers at Tom’s; at least everyone seemed to think so.

Irene Crawford Shrader and Walter “Glen” Dague began their brief and bloody crime career from their Wheeling base in 1929, and it was all over before Bonnie Parker even met Clyde Barrow. Their deeds, capture, trial, and debt to society were a sensation at the time, and the folks in Wheeling couldn’t get enough of it. That was just fine with Tom and Lizzie. Their exploits sold lots of papers and kept the store buzzing with patrons who discussed the infamous couple and consumed snacks and drinks at an enthusiastic rate.

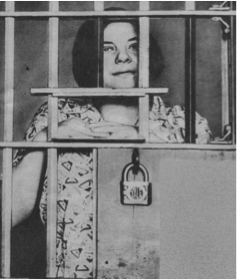

Irene was born in Benwood and had seven siblings. Her mother died when she was eight, and, while living with a sequence of relatives, Irene became a skilled practitioner of petty theft. She got married at age 15 to a man named Donald Shrader (Irene later changed the spelling to Schroeder to throw the police off course.) and had a son they named Donnie, but they divorced after 18 months of marriage. At age 20, Irene took a job in Wheeling as a waitress in one of the many diners that had sprung up in the Wheeling area.

“I swear I have seen her in here,” exclaimed one of the boys in Tom’s store one afternoon as he tapped the newspaper that carried a picture of Irene. “Right Mr. Minns?”

“Don’t ask me Bobby,” replied Tom with a smile. “Chances are I didn’t see her.”

Tom had been blind since he was a small boy.

It was different with Glen Dague. A number of the young men in the store were certain that they knew him. Dague, a World War I veteran, was a used car salesman, a Sunday school teacher at Steenrod Methodist Episcopal Church and, even more interesting, a Boy Scout leader.

“I remember him from our Pack meetings,” one young man said firmly.

“He was supposed to take us camping,” said another.

“Don’t be stupid,” interrupted a third boy. “He lives someplace out the Pike. What would he be doing down here?”

“He never really seemed that happy,” a lad unconvinced by the “out-the-Pike” argument said.

Dague, 33, was married and had two children in 1929, when he met Irene one day over lunch in the Princess Restaurant in Elm Grove where she worked. They struck up a conversation. Then, they struck up a more serious relationship. Then, Dague moved out of his family’s home and in with Irene—an action that, when it became widely known, drew a prompt dismissal from his job, his scouting duties, his Sunday school obligations, and the affections of his wife.

“She used to wait on my dad,” a loafer explained after reading a newspaper story about the infamous pair. “He said she was a flirt.”

“My dad bought a car from him,” said another boy. “It was junk.”

“You are both all wet,” an older boy said. “You are dreaming, and so are your dads.”

“Boys, boys,” interrupted Tom, calling for a break in the bickering. “How about an ‘Oh Henry’? Any takers? I just got a new box.”

Unable to find work, Irene and Glen concluded that their best alternative was crime. They bought pistols at a pawn shop, piled into an old Buick and hit the road with Irene’s 4-year-old son Donnie in tow. Their first mark was the Meadowland Inn in Cadiz, Ohio. They went on to rob gas stations and small stores, in Illinois, Missouri, Tennessee, Kentucky, Ohio, and Pennsylvania before heading home to Wheeling to celebrate Christmas in 1929.

“I think I saw them with that kid Donnie in line to see Santa at Stone and Thomas,” speculated a usually quiet boy leaning against the pop cooler.

“Nah, it was Cooey Bentz,” snapped his brawny buddy standing next to him.

“I think I saw them at the Centre Market picking out a Christmas tree,” offered an even more confident-sounding girl holding the newspaper open to the page with a story about the pair.

However they spent Christmastime in Wheeling, and on Dec. 26, Irene, Glen, and innocent little Donnie hit the road again, this time with Irene’s brother, veteran criminal Tom Crawford, along as back up. They stopped in Butler, Pa., spent the night at the Arlington Hotel, and attacked a grocery store at 11:15 the next morning, tying up the store manager and an elderly customer after relieving the cash register of its contents and the victims of their wallets. They sped off toward New Castle, Pa. Moments later, 25-year-old Pennsylvania State Highway Patrol Corporal Brady Paul’s phone rang in his office in New Castle. Alerted of the robbery and of the suspects’ approach, Paul and partner Ernest Moore jumped on their motorcycle and sidecar and headed out on the highway to attempt an intercept.

At around noon, Paul and Moore did indeed intercept the suspects’ car. Witnesses told later how Paul approached Dague, who was driving, and asked for identification while Moore stood at the rear of the detained vehicle. Dague came out firing his pistol and hit Paul in the left leg. Crawford, meanwhile, fired on Moore from inside the vehicle, hitting him in the nose. A second bullet grazed the side of Moore’s head. Moore went down and fell unconscious. By this time, a calm Irene stepped from the car and fired on Paul, hitting him in the arm.

He had his hands up and was backing away when she fired again, this time hitting him in the abdomen. The suspects jumped back into their car and sped off. Paul staggered behind a telephone pole and tried to return fire before dropping to his knees and blacking out.

“Holy cow,” exclaimed a chubby boy when that account was read aloud in Tom’s store. “She gunned him down with his hands up.”

“That’s what the cops are saying,” answered his companion. “Who knows what happened out there.”

Both officers were taken to Jameson Memorial Hospital. Paul died at 12:55 p.m. before doctors could complete surgery on his wounds. Moore made a full recovery. As for Irene, Glen, Donnie, and Tom, they were off and running. They abandoned their bullet-riddled car, stole another, and, on their way through the Ohio Valley, dropped Donnie off at Irene’s father’s house. When the police found the abandoned car, they found a receipt for the purchase of a woman’s scarf from a department store in Wheeling in the back seat. The police went to Wheeling and interviewed a clerk who identified the buyer as Irene.

“Wow, you can’t get anything past those old lady clerks up at the Hub,” observed one of the loafers.

The authorities quickly tracked down Irene’s father. On Dec. 31, investigators arrived at a house in Bellaire, Ohio where he was staying. Young Donnie appeared and offered up information that astonished the police.

“Mommy shot a cop just like you,” Donnie said. “Uncle Tom shot another one in the head. He shot right through the windshield.”

“Jeepers, what a goof,” said a boy in Tom’s store when the story about Donnie’s remarks was read aloud. “How stupid can you get?”

“You are the goof,” answered a girl. “Donnie is only 4 years old! I bet you weren’t so smart when you were his age. You aren’t too smart now.”

Glen and Irene split up from her brother Tom, had close calls with police in St. Louis and Dallas, and picked up an ex-con hitchhiker named Ackerman before finding themselves in Pinal County, Ariz., where they kidnapped a deputy sheriff and engaged in another gun battle that wounded two officers. They managed to speed away into the night. Their captive managed to escape. Forced to abandon their car, the trio set off on foot into the foothills of the Estrella Mountains. A posse of 75 local lawmen with air support from an Arizona-based flier tracked them down, and yet another gun battle ensued during which a deputy sheriff was critically wounded. Out of ammo and facing hopeless odds, Glen and Irene surrendered and were extradited to Pennsylvania. Arizona regretted the extradition because on Jan. 29, 1930, the wounded deputy died of his injuries.

Now the media were on fire and identified Irene as the leader of the gang. They called her “Blonde Trigger,” “Iron Irene,” and “Gun Girl.” One of the reporters filing dispatches from the trial was a young New York City reporter named Edward V. Sullivan, who would 18 years later begin hosting a long-running variety show on television that became known as the Ed Sullivan Show.

Tom Minns never failed to sell out all of his newspapers once the trial began in Pennsylvania. He ordered extra copies every day, and customers lined up to snatch them up and read about the famous Wheeling crime couple. To Tom’s great pleasure, many stayed in the store to talk about the case.

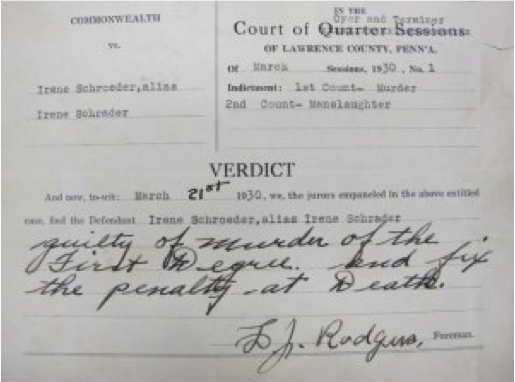

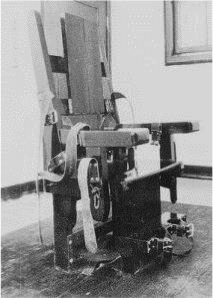

By late March 1930, both trials were over, and Irene and Glen were found guilty and sentenced to death in the electric chair. On Monday, Feb. 23, 1931, Irene was executed first. Glen’s execution followed a few moments later. Both occurred at the Rockview Penitentiary in Bellafonte, Pa.

On Tuesday, a boy in Tom’s store read a newspaper account out loud to a hushed crowd of loafers. The story relayed how Irene went first promptly at 7 a.m. Dague’s former Sunday school pastor, Harold Teagarden, had made the trip from Wheeling to try and comfort the pair. He walked with Irene part of the way until she turned to him and said: “Please stay with Glen. He will need you now more than I do.”

“’No hysteria, no sobs, no pleas for human mercy,” the boy read. “There was almost a carefree attitude about Irene. There were no muscular tremors as she entered that cold, dank cheerless room, no drawing back in horror, nothing but a matter-of-fact attitude that seemed to bespeak a haste to get the whole thing over. As the Rev. Lauer (prison chaplain Carl F. Lauer) walked slowly into the room ahead of her, he repeated the Twenty-Third Psalm. As the gruesome leathern mask went down over her face, obliterating almost all signs of it, not even did she wince or cry.”’

Irene, the first woman ever put to death by electrocution in the state and only the fourth woman ever put to death by electrocution in the entire country, was declared dead at 7:05 a.m. Dague was marched out to the same fate and was declared dead at 7:13 a.m.

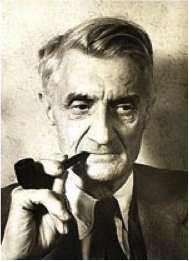

The executioner was Robert G. Elliott, who had put Sacco and Vanzetti to death in 1927 and who would do the same for Lindbergh Baby kidnapper Bruno Hauptmann in 1936. Irene was buried in the family plot in Mt. Rose Cemetery (now Greenwood Cemetery) in Bellaire. Oddly, Glen’s widow claimed his remains. She had him buried next to his mother and sister in Sand Hill Cemetery near Wheeling.

Irene’s brother Tom roamed free until 1933, when he was killed in a gun battle with the authorities in Morehouse, Mo. Donnie grew up to serve in World War II and Korea and eventually worked on the U.S. space program.

But, when told of his mother’s demise, the little boy said, “I bet my Mom would make an awful nice angel.”

“What did I tell ya,” said the boy who commented earlier about Donnie. “He’s a goof.”

“Oh shut up,” responded his antagonist.

Glen and Irene created quite the long-running media frenzy in Tom’s store and gave the loafers a lot to talk about. Most were convinced that they had experience with the infamous couple before they went bad and loved to tell their stories while consuming drinks and snacks and smoking cigarette after cigarette.

Tom just chuckled and made darn sure the pop cooler was fully stocked.

There’s an interesting story on a website called victimsofthestate.org about Marshall County residents Frank and Norma Howell, who were actually arrested and convicted of robbing a service station outside of Moundsville in 1929. Irene and Glen were the real culprits. Frank and Norma were pardoned of the crime only after Irene confessed while awaiting execution in Pennsylvania.

There have been varying accounts of Irene and Glen’s crime spree. More information and pictures about the couple can be found on the Lawrence County Memoirs website. Well-known Wheeling newspaperwoman Michelle Blum wrote an article about the couple based on her interviews with local historian William Carney. A great number of additional details, including executioner Elliott’s writing on his work, are available at murderpedia. More photos are available here.

Read more Mabel Files:

Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: Lindy Visits Wheeling

Part 3: T.J. Minns and his “Pal”

Part 4: Music, talk, and danger inside the Minns’ Confectionary

Part 5: Stogies, Sandwiches, and Crocheted Lace

Part 6: The Minns Confectionary Feels the Loss of a Jazz Giant

Part 7: Wheeling’s Underworld and Big Bill

Part 8: When George Met Mabel