“Young lady,” whispered the old man to Mabel Minns as he moved slowly and quietly between weathered gravestones and pointed a bent, wrinkled finger toward an unusual mass of granite and glass. “Do you know what Henry Clay’s soul, searing fire, and that monument have in common?”

“Young lady,” whispered the old man to Mabel Minns as he moved slowly and quietly between weathered gravestones and pointed a bent, wrinkled finger toward an unusual mass of granite and glass. “Do you know what Henry Clay’s soul, searing fire, and that monument have in common?”

It was a gorgeous, unusually warm spring morning in 1941. On a whim, Mabel had taken a bus ride with a girlfriend to explore Wheeling’s Greenwood Cemetery with its hulking old oak trees, ornate monuments, above-ground crypts, and abundance of speedy gray squirrels. They had specifically set out to search for one of the most famous spectacles in the cemetery—the large monument marking the grave of Jacob Thomas, co-founder of the popular Stone and Thomas Department Store in Wheeling.

Mabel and her friend didn’t know where the monument was. They decided to split up to cover more territory in the sprawling cemetery. That’s when the well-dressed old man approached her out of nowhere and posed his curious question.

“Excuse me?” Mabel responded a bit unsettled by the unusual question from the unusual man.

The old man walked closer with the aid of a thick, worn walking stick that had a golden knob at its top.

“You no doubt came here to see old Jacob Thomas’ monument—the one with the life-size statue of the man with the two women on either side of him,” he said in a soft feeble voice. “Many come to see that. But, you need to look at that one over there. You will not be disappointed.”

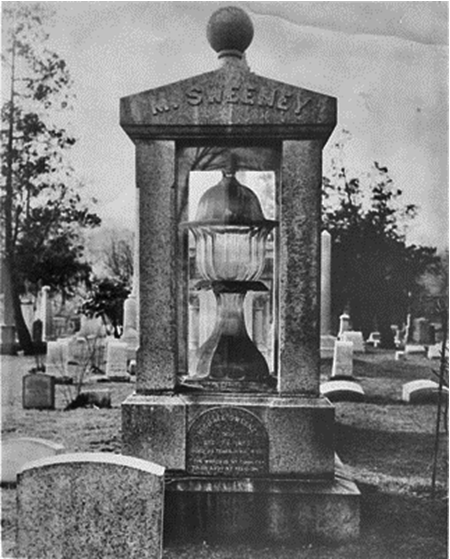

He directed her gaze to a monument with the name “M. Sweeney” across the top. It was all granite, had four legs that held up a matching, pointed slab with a large ball at its peak. Beneath that slab, encased in thick clear sheets of glass on four sides appeared to be the largest glass punchbowl that Mabel had ever seen. The punchbowl was made of ornate glass that stood nearly five feet tall and was capped by a heavy glass lid that rose to a sharp point. Mabel figured it must have weighed hundreds of pounds.

“I think I have heard of this,” Mabel said letting her curiosity overcome her suspicion of the old visitor. “But I don’t know why it is here.”

“I can tell you that and much more young lass,” the old man said as he pulled his heavy, black wool coat tighter. “That work of art was made in 1844 here in Wheeling. There were three of those vases made. They were called ‘float bowls’ then. There’s a bench over there close to the monument. Help me there, and I’ll tell you the story.”

Mabel was hooked all right, but she was still reluctant to wander off in the cemetery with a complete stranger, even if he was a gentle old soul that seemed harmless. She saw a groundskeeper nearby cutting grass, and she knew her friend would be appearing at any moment, so she hesitantly grabbed the old fellow’s elbow and helped support his shaky walk over to the Sweeney monument and the bench that was nearby. He was light as a feather.

“Wheeling was the gateway to the West,” the old man said as he lowered himself on the stone-carved graveside bench. “It was becoming a transportation hub. There were industries cropping up and people were flocking here to get the jobs that were created. Two were Irish brothers who moved here from Pittsburgh. Their name was Sweeney—Michael and Thomas Sweeney. In Pittsburgh they learned how to make cut glass items and that’s how they intended to make their fortune here in Wheeling.”

“What’s cut glass?” Mabel asked.

“Cut glass is glass that has been decorated entirely by hand making cuts in the piece with rotating stone or metal wheels that were powered by steam,” the old man answered. “The cuts were made on what was a smooth surface of glass by very skilled men to produce designed patterns in the glass. Look at the float bowl. See how those scallops and those ridges? They cut the glass to get those shapes.

“Sweeney glass was cut in the English and American styles and were shipped everywhere. At the turn of the century, almost half of all glass tableware came from either Pittsburgh or Wheeling. But to grow and become successful as a glass company in those days you had to do everything you could to get your products out there in front of the public. That meant sending examples of your work to exhibitions in the bigger cities. The Sweeneys made lots of products, but they really wanted to grab some attention, so they designed and had their highly skilled glass men make that float bowl there and two others out of lead glass.”

“What is lead glass?” Mabel asked.

“It was also called flint glass,” he answered. “Glassmakers added lead oxide in their processes replacing calcium. That made it easier to melt and easier to manipulate. It also created a very clear and impressive glass when finished.

“All three float bowls were 4 feet, 10 inches high, could hold 16 gallons of liquid, and weighed 225 pounds. Each one consisted of five pieces. Each of them was made by being blown into a wooden mold and then cut by hand.

“Those Irish lads were not only good marketers, but they also were good at making friends with powerful people who could help their business. They were good friends with Moses and Lydia Shepherd, who built Shepherd Hall—a fine stone mansion on Wheeling Creek. They were the ones who got the National Road to run through Wheeling instead of up north closer to Wellsburg and Weirton. They did that by wining and dining important politicians of the day and none was more important than Henry Clay of Kentucky, who had been a U.S. Senator and U.S. Secretary of State before settling in as Speaker of the House of Representatives. But he always wanted to be president. He ran first against Andy Jackson, and then two more times.

“Clay got close to the Shepherds, especially Lydia, but that’s another story. The Shepherds weren’t just trying to help Wheeling. Moses wanted the contracts to build some of the bridges for the National Road project. And he got them. That bridge out there over Wheeling Creek near their old home is one that he built.

“It was on one of Clay’s numerous visits to Shepherd Hall that the Sweeneys were introduced to him at one of the social affairs that Lydia held in the mansion’s second floor ballroom. The Sweeneys and Clay discovered that they had some things in common—a love of whiskey and a strong desire to make sure that cheap foreign glass imports didn’t put American glass companies out of business.

“Clay got a couple of bills passed that set high tariffs on imported glass and that helped the Sweeneys and other glass makers thrive by stopping foreign companies from dumping their cheap glassware in the United States. Michael had the idea to give one of the three giant float bowls they made to Clay in gratitude for all he had done to help them and their industry with the tariffs. That was in 1844, just after Clay made his second unsuccessful run for president, this time against James Polk. Clay was in what was called the Whig party. The Sweeney’s were important supporters of the Whig party. Clay took the float bowl, sent the Sweeney boys a nice letter and had it installed at an estate he called Ashland in Lexington, Ky. The Sweeney’s also gave Clay two very special cut glass whiskey decanters as a more personal gift.

“After another failed presidential run in 1848, Clay retired to Ashland. But, then the legislature of Kentucky elected him to the Senate again, and he wrestled with compromises on slavery that were intended to prevent war between the North and the South, the admission of Texas into the Union, and the Mexican War that made him internationally famous, but my story is not about all that.

“Old Clay never was much of a religious man, but when he turned 70 in 1847, he decided he would join his wife’s church there in Lexington and make sure his soul made it to where he reckoned it should end up. The problem was the church wouldn’t let him in unless he was baptized. To further complicate the situation, the church was being rebuilt and could not accommodate a baptism of Clay’s importance. So, they decided to have the ceremony right there in the parlor of Ashland.

“Guess what they used to hold the holy water that baptized old Henry Clay, his daughter-in-law, and three grandchildren who were also baptized that day?”

Mabel looked up at the punchbowl monument a few feet away.

“Yes, lass, that’s right. They used their fancy five-foot-tall Sweeney float bowl from Wheeling. It must have made quite an impressive baptismal.”

“Whatever happened to Clay’s punchbowl?” Mabel asked.

“After Henry died in 1852 and the family was settling the estate, the piece was moved to a warehouse in Lexington till they could figure everything out. The warehouse caught fire one night. That float bowl melted like ice on a hot summer day. It was wiped off the face of the earth.”

“After Henry died in 1852 and the family was settling the estate, the piece was moved to a warehouse in Lexington till they could figure everything out. The warehouse caught fire one night. That float bowl melted like ice on a hot summer day. It was wiped off the face of the earth.”

“What about the other one?” Mabel interrupted.

“The Sweeneys believed in sending their best work out and about to draw attention to their wares,” the old man said in what Mabel began to identify as a faint Irish accent. “They sent the remaining two float bowls all over for display. One bowl went to exhibitions in Philadelphia and New York City, where it won medals and prizes for its magnificence. In 1851, they were invited to display one of the bowls at the Crystal Palace Exhibition in London. Workers were getting one of the bowls ready for packing and shipping overseas at a Sweeney warehouse in Pittsburgh when fire struck again and you can guess what happened. It was a tragedy, and it left just one Sweeney float bowl in existence.”

“What about this one?” Mabel asked pointing to the Sweeney tomb. “Why is this here?”

“As with many Irish lads, there were fights and disagreements, and the one that broke the partnership was over money,” the old man answered. “Michael pleaded for a loan from Thomas. Michael wanted to build a big new mansion on Main Street in Wheeling. It was a wasteful notion. Michael never did spend his money wisely. In Michael’s anger, he said hurtful things, things no brother should say to another. They never spoke again. Thomas left the company, Wheeling and the last remaining float bowl.”

The old man put down his walking stick and dabbed his watery eyes with a white handkerchief that had “TS” embroidered on one corner.

“When Michael died in 1874, he left instructions to incorporate the last Sweeney float bowl into a grand monument to mark his tomb, and that’s what you see here today.”

“Wasn’t Thomas upset about losing the last punchbowl and having it put out here in a cemetery?” Mabel asked.

“He didn’t know about it until he visited Michael’s grave a few years after Michael died,” the old man answered. “It was quite a shock to discover it entombed here just like Michael, cold, gloomy and dead as dead can be. Now it sits here with Michael, trapped, forgotten, and alone, just like people’s memory of the Sweeneys.”

“What became of Thomas?” Mabel asked just as she heard her friend call her name from behind.

Before the old man could answer, Mabel turned and ran to the crest of a hill to meet and escort her friend to the Sweeney monument so she could share the story of the entombed punchbowl, Henry Clay, Michael and Thomas Sweeney and their place in history. When she returned to the Sweeney monument and its encased giant punchbowl, the stone bench was empty.

***

In 1948, many citizens of Wheeling became concerned for the safety of the Sweeney punchbowl, and after 74 years of sitting atop Michael Sweeney’s grave, it was removed for safe storage. It was on display for many years in the Oglebay Mansion Museum. Today, it is on display at Oglebay Institute’s Glass Museum in Oglebay Park and is among its prized possessions. The empty granite M. Sweeney monument still stands in Greenwood Cemetery.

In 1948, many citizens of Wheeling became concerned for the safety of the Sweeney punchbowl, and after 74 years of sitting atop Michael Sweeney’s grave, it was removed for safe storage. It was on display for many years in the Oglebay Mansion Museum. Today, it is on display at Oglebay Institute’s Glass Museum in Oglebay Park and is among its prized possessions. The empty granite M. Sweeney monument still stands in Greenwood Cemetery.

In gratitude for his help in locating National Road within footsteps of their stone mansion in Elm Grove, the Shepherds erected a stone monument in tribute to Clay. The property was later owned by Alonzo Loring after Lydia Shepherd died, and it remained in the Loring family for decades. Lucy Loring Milton renamed the property “Monument Place” in 1907. The Osiris Shrine Temple purchased the property in 1924. The monument to Clay no longer exists.

Henry Clay’s estate, Ashland, is open to the public in Lexington, Kentucky where visitors can see the parlor where he was baptized using his Sweeney float bowl.

By the late 20th Century, the cheap glass imports that Clay and the Sweeneys fought more than 100 years ago eventually penetrated the U.S. market with devastating results, forcing closure of nearly all the great American glass plants. The Sweeney glass enterprise closed around the time of Michael’s death in 1874.

For more about the Wheeling glass industry, visit http://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/wheeling-history/wheeling-glass-industry-1886/2731

For an article about Henry Clay’s baptism at Ashland visit http://historyofahousemuseum.com/tag/sweeney-glass/

For more details about cut glass, read this article