Photography archived by James Thorton

(Writer’s Note: This is the 10th and FINAL story in this series that has concentrated on the organized-crime scene in and around Wheeling during the past century.)

Helter Skelter, Snapped Necks, and Real History

It just kind of faded away one day.

And because of big news.

Names and crimes in print and publicly spoken thanks to the local press supplied the people with all the allegations against Paul “No Legs” Hankish, and yes there were confirmations, too, for those who always owned their suspicions based on whom they knew, what they saw and heard, and how they were guilty themselves.

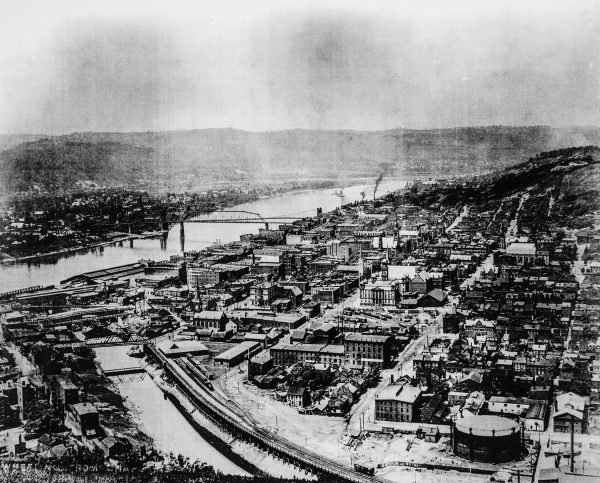

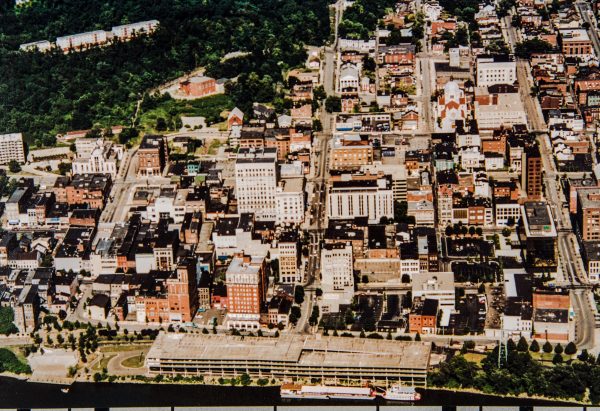

It was “The Wheeling Mob,” a collection of crooks and creeps from Wheeling and beyond breaking laws and selling addiction in so many different ways. Running numbers proved infamous, and so did the poker machines, but pimping hookers, pushing junk, pawning stolen property, and perpetrating crimes that involved shooting, slashing, or stabbing all took place hidden away for few to witness.

In many cases most of the criminal activity was in plain view, though, to anyone paying much attention. The poker machines and spot sheets were mainstream, and every bar’s bartender had a number to a bookie because no one cared; not the waiters and waitresses, and not the salesmen or the gift wrappers or the stock brokers or the doctors in downtown Wheeling. The cops knew, too, and while they could prove very little when it came to the gambling, officers did bust brothels, raid bars in search of underage drinkers, and enforce kid-age curfew laws, too.

Arresting Wheeling’s Mob bosses didn’t happen very often, but it did occur.

“Big Bill” Lias got busted the old-fashioned way – tax evasion – but when Paul Hankish was arrested, found guilty, and twice sent off to prison, the felonies were far more blue-collar. Swiped jewels, laundered stolen money, smuggled beer and booze, and burglary, but hey, in the 1970s the warden of the West Virginia Penitentiary in Moundsville even ordered a special design for Hankish’s cell so that his wheelchair could slide into it.

Once the indictments were released in early 1990, and after most of the arrests were made, the gig was up and out in the open. Everyone knew most of it, but not all of it. The newspaper printed each and every of the 21 pages full of charges, and the local folks were distraught with terms like “murder” and “fraud” and “extortion” listed within the long list of charges.

Suddenly gone were the spot sheets; the coke and the weed dried up; much of the street activity vanished once the raids and ensuring roundups scattered the troops once loyal to anything related to the Paul Hankish organization. The rats ran, the barflies flew, and the couriers carried it far away from here.

“After Hankish plead out during the trial, Wheeling’s organized crime became unorganized crime. It became that way leading up to the trial. Although the grand jury heard the evidence in Elkins before the indictments were released, there were a few people from this area who were on that 25-person grand jury,” former FBI agent Tom Burgoyne said. “The members of that grand jury were sworn to secrecy but the word still got out, and those guys didn’t want to be called in as a witness or part of grand jury No. 2, so everything got tucked away. No one wanted mentioned.

“It all dried up very quickly, and that’s when it all became very helter skelter,” he said. “When Hankish ran the operation, it was very organized with very street- savvy people involved during those days. They knew what they were doing, but when the drug traffickers began the ghetto distribution it got uglier than I’ve ever seen before.”

The trends in criminal activity shifted, too.

“Back in those days anyone who lost over $5,000 in a home invasion qualified within a federal statute, so we investigated those crimes, and in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s we had a lot of those burglaries in this area,” Burgoyne said. “I can’t tell you how often those crimes involved jewelry, collectible coins, and other items that were big-ticket items. They didn’t bother with the small stuff.

“But after the Hankish trial total organizations were dismantled, and that included entire families that operated the machines and the numbers for decades,” he recalled. “Most of those families lost those machines, and that was a big deal. Even if it was three or four machines, those things were moneymakers, and they were missed when they went away.

“But it was the helter skelter drugs that took over, and that’s still true today. That’s all you hear about whether it’s the trafficking or the crimes that take place for people to get money to feed their addiction. It’s now all about the addiction and not the party anymore.”

Burgoyne and his federal colleagues continued concentrating on the poker machines after Hankish was taken away, and all law enforcement agencies throughout West Virginia also initiated various investigations in all 55 counties because Mountain State lawmakers were studying how to legalize and tax the gambling machines. The result was the Video Lottery Act passed in 1994.

“After the trial the illegal poker machines did continue operating for a few years, and one of the distributors of those machines became the target of a federal investigation,” Burgoyne said. “It involved the Dobkin Brothers business, and it was a big case here. We seized a lot of machines, and many of them were the slot machines with the handles that the people pulled.

“Those machines were everywhere still, even after the trial. From New Martinsville to Chester. Everyplace had them,” he said. “And it wasn’t all run by the Mob, either. In a lot of cases those machines were owned by businessmen who did that for a living. But that came to an end, and, of course, these days those machines are still everywhere, but the government runs them now.”

Exhumed from Rest

She was a hooker in the 1960s, and she was a smart hooker. Smart enough to operate a brothel in Center Wheeling, work only two weeks a month, and then return to her Canton, Ohio, home for the other two weeks. Her name was Carla Dellerba, a beautiful Italian immigrant fearful of deportation. She attracted Hankish’s attention, but not because of her long, dark hair and lean figure, unfortunately.

“I don’t know how she ended up here, but she was definitely here,” reported Burgoyne. “In the prostitution business you couldn’t work 30 days a month. You had to take a couple of weeks off because at that time it was crazy. People were coming through those doors at all hours of the night.

“A few months before the Hankish trial was set to start in July 1990, (Wheeling police lieutenant) Jimmy Wright and I went to a prison in Chillicothe, Ohio, to interview Ronnie Asher. He was serving time for a 1978 murder after being involved with a killing of an employee (Thomas Carney) of an A&P grocery store in Martins Ferry,” he continued. “We knew he was a strong-arm guy for Hankish when he was on the loose, and we knew that he was a debt collector.

“The word on the street was that if you didn’t pay off your gambling debts Asher would pay you a visit. That’s how it worked, but when I interviewed him in that prison, I knew he would try to make a deal for himself because he only had a couple of more years left on his sentence. He wanted out as soon as possible and was willing to share some things with us.”

Hankish found out in the mid-1980s that Dellerba was named in a federal investigation in Kentucky and was subpoenaed to testify about the prostitution activities she was involved with in the Louisville area. Hankish, the retired federal agent offered, was concerned she also would include information about her Center Wheeling operation.

So “No Legs” hired Asher to assassinate her.

“Asher was being pretty free with what he was telling us during that interview, and he started telling us about some of the things he used to do for Hankish. His trip to Canton was one of those things,” Burgoyne said. “He told us he was sent up there to kill Dellerba, and Asher told us he agreed to do it.

“Asher went to Canton, found the address, and knocked on her door. But she wasn’t home, so he returned to Wheeling and said he didn’t connect, but Ronnie Brice knew they had to connect. Brice owned and operated Ron’s Value Center, but he was very involved with the prostitution ring and knew they had to do what Hankish ordered,” he continued. “So they went back up to Canton together, knocked on her door, and she was home and she invited them in. Asher said she went to the kitchen to get them a cup of tea, and he said that’s when he followed her into the kitchen.”

Asher then told Wright and Burgoyne that he grabbed Dellerba from behind and snapped her neck the same way he had claimed victims before. He then let her body to fall to the floor and returned to the living room and told Brice she was dead. But Brice, Burgoyne said, needed to know for himself.

“He wanted to make sure because of how scared of Hankish he was, so he went to the kitchen, got a kitchen knife out of one of the drawers, and he shoved it into her chest. Then they left, and that was it,” Burgoyne recalled. “Asher told us that the county coroner up there determined the cause of death to be suicide. Hankish had some kind of connection to make that happen.

“It’s very rare that you see someone taking their own lives by sticking a knife into their own chest because it’s not a very quick way to die. So based on that information, we filed to have the body exhumed for a new autopsy,” he said. “I still remember those photos because after all the time that had passed, she still had flesh and still had her black hair. And when they conducted the second autopsy they found the broken neck and verified Asher’s story. That’s all we were after.”

It wasn’t suicide. It was murder, and Asher testified on July 18, 1990, that Hankish called on him more than a few times to work on the kingpin’s odd jobs. The enforcer was compensated as much as $3,000 a hit, and at times Hankish supplied the weapons.

Asher told U.S. Judge Robert Merhige about a Black Muslim in New Jersey (“I couldn’t find the guy. He must have gone underground. I waited three weeks.”), and he also shared the tale about Dellerba. He testified that he didn’t know her, and he wasn’t aware of the reason why Hankish wanted her dead.

He just killed her.

Brice, Burgoyne offered, was more brains than brawn, and no one seemed worried how the merchandise landed inside Ron’s Value Center. Apparently my own mother did not care because during the summer of 1981 that’s where she took me for back-to-school clothes shopping. Our search included nice khaki and grey slacks, button-down dress shirts, and dress belts with preppy logos.

I recall we walked away with it all.

“Most of what was for sale at Ron’s Value Center was stolen by Hankish’s crew. Not all of it, but most of it. There were stolen tools, stolen suits, stolen garments – whatever they could sell and whatever didn’t have a serial number to it,” Burgoyne said. “Then the other stuff was just cheap garments they’d get out of New York City, and they would cut the tags inside so people would think they were stolen. That way the people thought they were getting great deals. Brice was smart that way.

“But Ron’s Value Center was really a front for Ron Brice’s prostitution activities. None of that happened at the store; that stuff took place in a lot of the buildings between 24th and 26th streets,” he explained. “And Brice was directly connected to Hankish. Everyone knew that.”

Hello There, Organized Crime

Hankish, like so many who get locked away in prison, refused to quit fighting back against his incarceration and the people he believed helped land him behind bars. While he reached out to people he believed were allies on the outside, most of them turned their backs in fear of an indictment of their own.

One person he appeared to be upset with was a Wheeling attorney known as, “Gummer.” Hankish had hired him often during his Mob career and within letters composed in 1994-95 and discovered just recently in a hidden drawer inside one of Hankish’s former Wheeling properties, the gangster seemed to be very angry with the lawyer. “No Legs” scribed that “Gummer” refused to return his phone calls and his letters, so the prisoner waged an attack against the esquire.

Hankish released to many of Wheeling’s most prominent citizens a list of what he alleged “Gummer” had gossiped about them, and that mailing included federal and local judges, congressional members as well as state lawmakers, Wheeling-area businessmen, media outlet owners, attorneys, prosecutors, and assassins.

“When I look at all of those names, I believe Paul was trying to get back at some of the people who testified against him and people he used to do business with during his heyday,” Burgoyne said. “He was definitely unhappy with ‘Gummer’; that’s for sure, but that’s something I wasn’t aware of.”

Within one correspondence, Hankish typed, “Gummer, what is not mentioned here is not forgotten. I must keep some surprises for you. But all are coming, I assure you of that.”

At the end of the last letter of what was found inside the former residence was this very cryptic passage: “I hope you suffer a horrible death.”

“Something happened there because we always saw them being pretty chummy before Paul went to prison,” Burgoyne said. “There were a lot of twists and turns in that case from the very beginning, so it’s not surprising to me that it continued in some ways after he was finally locked away.

“I was working my third day in Wheeling as an FBI agent when I was first introduced to the organized crime that was taking place here in the Wheeling area because of a beer truck that was hijacked in Huntington that ended up in Bridgeport. When they found the truck, though, the beer wasn’t on it,” he said. “We later found hundreds of cases of beer in East Wheeling garages. So this one case was a lot of my FBI career here in Wheeling because it really started during that first week.”

And Burgoyne considers the conviction of Paul Hankish his landmark accomplishment as a law enforcement officer on the federal and county level.

“That’s because of who Hankish was and what he was doing,” Burgoyne said. “Most FBI agents don’t work in a place where they can go to dinner and see his suspect across the room from him, but that was my reality working in Wheeling and working this case with so many other great agents and officers. It was a team effort in every sense of the word.

“I’ve arrested hundreds of criminals, but being a part of bringing Hankish down was the biggest case of my career in law enforcement, and that’s because he was so cunning. I mean, this guy had no legs, and that meant he had to rely on someone else to be there to do almost everything for him,” he said. “Somehow he survived that bombing, and he survived to live a pretty good life until it all caught up to him. But for a long time he was very cunning. He knew how to play people. He knew how to scare people. And he knew how to play up to the right people.”

Except maybe Lias, Burgoyne believes, and that’s because the retired federal agent is confident it was “Big Bill” who ordered the car bombing that created the “No Legs” legend and gave birth to a whispered-about folk hero up and down the East Coast.

“Everyone around here knew it was Lias who ordered the bombing. Everyone knew because Hankish didn’t have any other enemies at the time of the bombing,” he said. “There may have been a few guys out there who weren’t happy with him because of his sexual activities. That stuff caused him some problems,” he continued. “But there wasn’t anyone out there in the early 1960s who wanted him dead.

“I guarantee you it was not the goal of ‘Big Bill’ Lias to create the folk hero that Hankish became after surviving that bombing. You don’t put a bomb like that in someone’s car and expect them to live, and if he had died right then, 12 months later chances are no one remembers who Paul Hankish was.

“If you think about it, if Hankish would have died in that bombing, there would have been no one to take Lias’ place as the Mob boss around here. All you have to do is look at the characters that Lias and Hankish surrounded themselves with, and it’s pretty easy to see there are no masterminds in there. Not one of them could have been a Paul Hankish.”

Like It or Not

I had overheard conversations and seen the envelopes exchanged from one man to another well before beginning my research into what I was hearing and seeing for myself as a boy and as a teenager in the 1970s and 1980s. I didn’t know the contents of those small packages then, and I was unaware of what “shipments” were coming and going and just how far the reach was.

What I did know was that I was happy to get my hands on those spot sheets in those Linsly hallways and ecstatic when turning 20 poker points into 80 – for amusement only, of course – on one of those “Draw 80” machines that were in every bar I entered as a high school and college student. But I do not recall being aware of a link to the Wheeling Mob.

I was, however, familiar with the man with no legs. I saw him, on crutches or being pushed in a wheelchair, and he was in downtown restaurants, office buildings, theaters, stores, and in the courthouse. He was Paul Hankish, the unkillable man who ran the rackets.

In the very beginning of this series, Burgoyne set me straight; it was a “Mob” and not the “Mafia.” He said the Mafia was made up of family members who were of Italian decent, but the Mob, he insisted, was just that, a group of men with few rules but many goals, and making money was the top priority.

We learned about the rats that cooperated with law enforcement in an effort to reduce their punishments or to make their way out of town without a badge following, and we were told how the multi-million-dollar prostitution trade once worked in the Wheeling area and how drug addiction transformed it into something dirty and something very ugly.

How Hankish survived the January 1964 bombing in front of his Warwood residence is a question many continue asking even today, and because he refused to levy any official accusations against the perpetrator, something of an invincible man was born. Hankish took control of as much criminal activity he could corral even before Lias passed away in 1970, and by the “Crazy 80s” the Wheeling area was openly gambling and partying and buying stolen property.

And they were happy about it, too.

“Back in the ’80s the mob stuff was just part of the deal in Wheeling,” said Wheeling Councilman Don Atkinson, who has worked for Ace Garage for more than three decades. “It was something you know was there and expected to see when you went out on the town with your friends. Like I said; it was part of the deal.

“Back in those days you knew how to get involved if you wanted to, and you knew how to stay out of the way. The gambling part was nothing to anyone because everyone watched the games and putting down a couple of bucks on team wasn’t a big deal,” he continued. “I will say that the drugs were too obvious to someone like me because that’s not something I ever got into. But it was all over the place.”

And it was the cocaine that eventually led to the end, and after the FBI joined the Internal Revenue Service, the West Virginia State Police, and the Wheeling Police Department in an investigation that lasted nearly four years, the indictments surfaced, and the charges surprised a tri-state region.

Journalist Kim Loccisano offered us her perspective concerning her involvement in covering the Hankish trial 25 years ago for the Martins Ferry Times Leader, and her words that struck me the most:

“While I helped (reporter Patricia Neal) cover that trial, I remember realizing that the legends involving Bill Lias and Paul Hankish were not legends after all. It was real, and it needed to be understood as real,” she told me. “He was a real person, Hankish was, and those who were testifying were real people, and the fact was that all of things he was charged with happened to other real people.”

Paul Nathaniel Hankish was born on July 8, 1931, in Wheeling, and he passed away of kidney failure in a federal prison in Petersburg, Va., on May 11, 1998, at the age of 66.

He was not immortal, after all.

“I think everyone learned about some of the bad sides of Paul Hankish during that trial, and I think that’s why Hankish decided on the plea. I think he wanted to protect the good things people thought about him,” added Burgoyne. “I know a lot of people have paid a lot of attention to this story series because they either forgot about it or because they didn’t know everything about it. I know other people who haven’t been very happy about it, too, but their reasons are the wrong reasons.

“It’s part of our history whether people like it or not. It happened; trust me,” he said. “You just can’t focus on the positives when it comes to history. There always needs to be some reality in that history, too.”