A Weelunk Partnership with Archiving Wheeling.

For more Archiving Wheeling stories about local history through documents go to www.archivingwheeling.org.

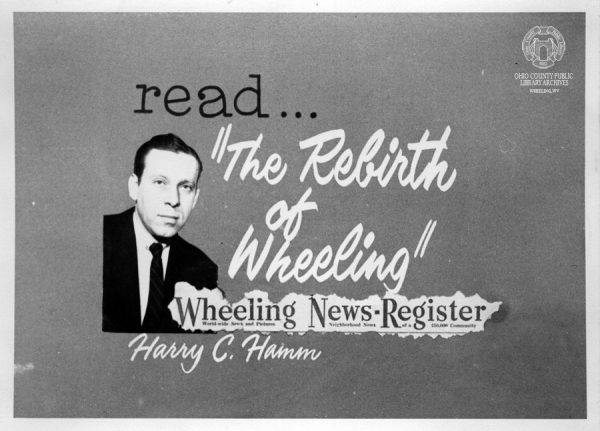

If you had tuned into Wheeling’s WTRF television station fifty years ago, you may have caught an on-air announcement for “The Rebirth of Wheeling,” a series of ten articles reprinted from the News-Register that told a “factual story of a great city’s comeback.”

The Wheeling Conference

The author, newspaperman Harry Hamm, had been a founding member of the Wheeling Area Conference on Community Development, which was established in 1953 to bring to the city the success of Pittsburgh’s celebrated postwar renewal. Indeed, the organization had formed following a speech at the Wheeling Civic Club by John J. Grove of the Allegheny Conference on Community Development, the business-backed group that spearheaded the Pittsburgh Renaissance. Grove’s presentation and offer of support made “a most profound impression” on his audience, who quickly resolved to form an organization that could break “the logjam” which had held up “many worthwhile and needed projects” in the city. In addition to Hamm, other city leaders helped start up the Wheeling Conference, including Robert Levenson, president of Reichart Furniture and John Neudorfer of Wheeling Steel. “All citizens who believe in Wheeling find themselves welcome,” President Wilbur S. Jones of the Stone & Thomas department store declared. We are “moving forward in giant steps and can become as great a city as its citizens want it to be.”1

Smoke Abatement

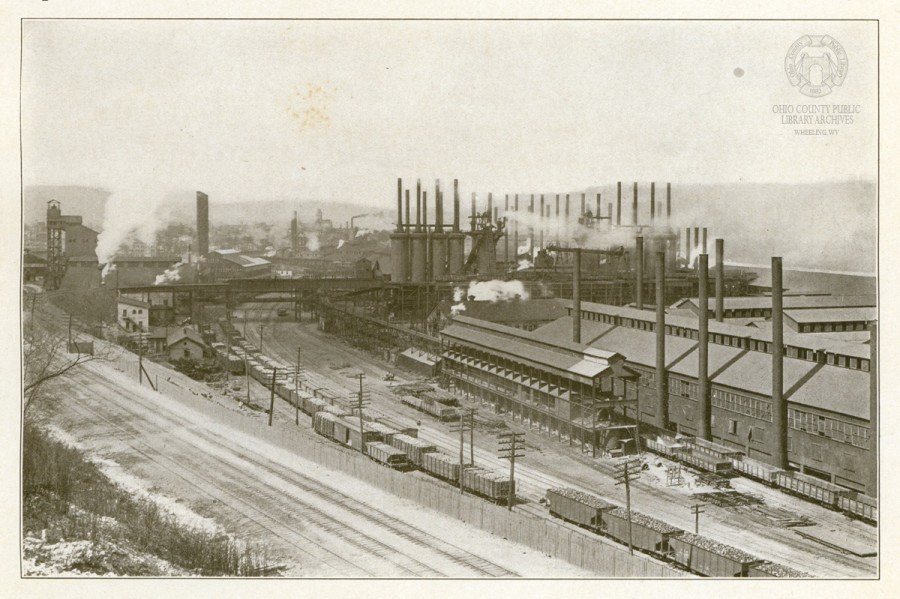

“The idiosyncrasy of this town is smoke. It rolls sullenly in slow folds from the great chimneys of the iron-foundries, settles down in black, slimy pools on the muddy street. Smoke on the wharves, smoke on the dingy boats, on the yellow river,—clinging in a coating of greasy soot to the house-front, to the two faded poplars, the faces of the passers-by. The long train of mules, dragging masses of pig-iron through the narrow street, have a foul vapor clinging to their reeking sides.”

–from “Life in the Iron Mills” by Rebecca Harding Davis“The coal smoke makes Wheeling at first, objectionable to the stranger, but barring this drawback there is hardly a pleasanter location for a city in the world … The verdict of eminent physicians is, that coal smoke is favorable to lung and cutaneous diseases, from the large amount of carbon, sulphur, and iodine contained in it. It is also antimeasmatic, which accounts for the few cases of remittent and intermittent fever in this section of the country.”

-from the 1885 Wheeling Saengerfest Guide

Despite the positive spin attempted by promoters of the German singing festival, most 20th century residents shared a less favorable opinion of Wheeling’s ubiquitous industrial smoke, one more in line with the perspective expressed by Mrs. Davis above.

Thus, as in Pittsburgh, conference members made smoke abatement their “number one project.” “When you drove downtown in the mornings,” recalled resident John B. Hunter II, ”you’d have to turn on your headlights at ten or eleven o’clock in the morning because of the smoke. “ Civic leaders successfully pushed for the enactment of an ordinance that resulted in the installation of more than $400,000 in smoke control equipment by the end of 1956. James Martin, the city’s director of air pollution control, signed the first arrest warrant under the new ordinance against the local superintendent of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad after observing cinders from a locomotive firebox, causing “more pollution than any citizen of Wheeling should be subjected to.”2

Infrastructure

The organization could also point with pride to tangible infrastructure projects, such as the construction of the 880-car Wharf Parking Garage along the river. As in other cities, the rise of the automobile presented a major challenge to a community designed around pedestrians, horses, and later trolleys. The mid-1950s witnessed a flurry of transportation improvements, including construction of the Ft. Henry Bridge as well as proposals for the Wheeling Tunnel and upgrades to US 40 and WV 2.

Better roads and bridges, however, brought even more vehicles to a downtown that “lacks adequate parking facilities for the thousands of shoppers, workers and casual visitors.” A recommendation by the Parking and Traffic Committee of the Wheeling Conference led to the creation of a municipal parking authority and the selection of the old wharf property at the foot of 12th Street as the site for the city’s first parking garage. In the summer of 1954, the newly opened garage was featured in the promotional video Wheels to Progress, directed by well-known filmmaker Ellis Dungan. 3

Urban Renewal

Drawing inspiration from the redevelopment of Pittsburgh’s downtown Golden Triangle, in November 1959 a group of Wheeling Conference members and public officials traveled to their larger neighbor for advice on starting their own urban renewal program. Shortly after their trip, the newly created Urban Renewal Authority of Wheeling, chaired by the Wheeling Conference’s Robert Levenson, submitted a plan to redevelop a large part of the Center Wheeling neighborhood, documenting numerous examples of “blight” as well as high rates of tuberculosis, infant mortality, juvenile delinquency, and arrests. For proponents, Center Wheeling was notorious for its taverns, brothels and slums, while a planned industrial park would “for the first time … attract satellite industries within its city limits.” However, we can turn for another perspective to Darlene Stradwick, who lived in the area as a child. “All the blacks lived in Center Wheeling,” she recalled. “It was great. There were family neighborhoods.” But, when “the state/federal projects came through, they moved from Center Wheeling to East Wheeling.”4

Urban Renewal Authority Images of Center Wheeling

What Went Wrong?

Despite the successes of the Wheeling Renaissance, Wheeling Conference members struggled to maintain the strong public-private partnership necessary for urban renewal. The city lacked the financial resources of Pittsburgh and local residents proved unwilling to raise taxes to generate the needed funds as civic boosters failed to garner the 60 percent support needed for passage on an urban renewal levy not once, but twice. Faced with the inability to mobilize sufficient votes for a property tax increase, Levenson helped organize the Downtown Wheeling Associates, a merchants group that approached city council with a proposal to increase the gross sales tax in order to meet the local obligations for urban renewal.

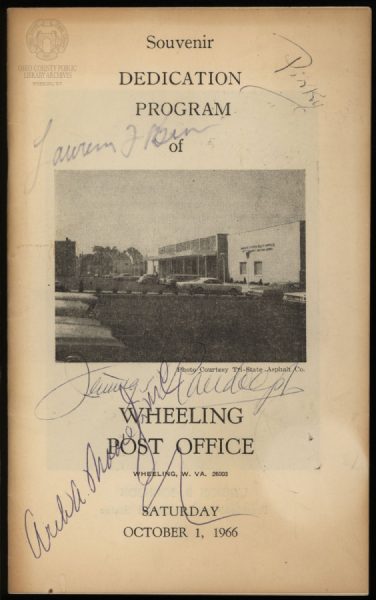

By the end of 1963, land in the scaled down project area was almost fully acquired, had been 50 percent demolished and was being advertised “for light industrial use” with “modern improvements” and “all utilities on site.” After the heroic efforts required to fund the Center Wheeling project, however, officials struggled to actually find industrial tenants. They eventually settled for a new post office and a trucking company – not exactly the catalyst for economic growth proponents had envisioned.5

The Wheeling Conference faded away by the mid-1960s with some of its activities folded into a new Chamber of Commerce. Despite the loss of its key proponent, the Wheeling Renaissance continued in the activities of the Urban Renewal Authority, which followed up its first project with another venture in Center Wheeling clearing land for an expansion of the Ohio Valley Medical Center. As this second, more successful development wrapped up by the end of the decade, civic leaders turned their attention to the thorny issue of what to do with the old Market Auditorium in the heart of the central business district.

The struggle over that site, which was demolished in 1964, would finally tear apart the fragile partnership that first made possible the Wheeling Renaissance.

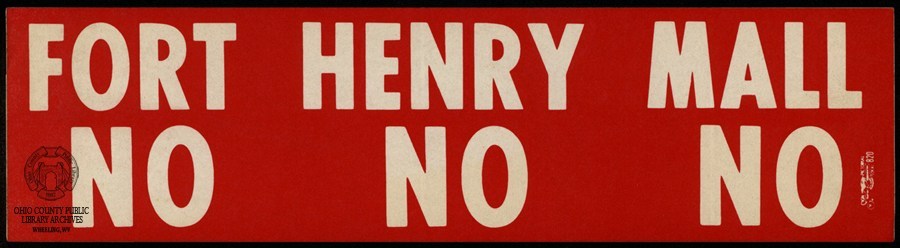

[This is the first in a series of three posts by Allen Dieterich-Ward on Wheeling’s past attempts at renaissance. Part 2 will explore the “Ft. Henry Mall,” and Part 3, the Wheeling National Heritage Area.]

Author’s Note

While writing his book, Beyond Rust: Metropolitan Pittsburgh and the Fate of Industrial America, Dr. Dieterich-Ward, Associate Professor of History at Shippensburg University, did a great deal of research at the Ohio County Public Library, frequently accessing the Wheeling Room and the library’s archives. He appeared at the library’s Lunch With Books, Nov. 24, 2015.

I first began research on Wheeling in 2003 looking through the creaky metal cabinets of the Ohio County Public Library’s Vertical File and reading the oral histories of the Wheeling Area Historical Database. Now more than a decade later, those materials are still central to telling the story of the Upper Ohio Valley as I do in my new bookBeyond Rust.

From the newsletter of the Wheeling Area Conference on Community Development to the original proposal for the controversial Ft. Henry Mall to David Javersak’s 1994 description of Steubenville’s abandoned urban core (“You could let off a howitzer … and not harm a soul), researchers and residents alike should be grateful for the foresight of OCPL staff in maintaining this invaluable glimpse into our shared history.

I’ve also benefitted tremendously from two more recent acquisitions generously donated by patrons. The Harry Hamm Papers cover the career of one of the city’s most productive and long-serving civic boosters, whose activities extended from helping to found the Wheeling Conference in 1953 to initiating the “Wheeling 2000” proposal for downtown redevelopment in 1987. Hamm’s involvement with the Benedum Foundation further emphasizes the close connections between the Upper Ohio Valley and Pittsburgh, a key theme of my research and writing.

The Robert L. Levenson Archives, donated in 2010 by Levenson’s son, opened up another important window into Wheeling’s post-World War II development. Levenson, the president of Reichart Furniture, helped start the Wheeling Conference and served as the first chair of the city’s Urban Renewal Authority. He was also the founder and first president of the Downtown Wheeling Associates, a merchant’s group established, in part, to support the urban renewal program in Center Wheeling. Levenson’s collection is particularly interesting because of his emergence in the late 1960s as a fierce opponent of urban renewal in the central business district, a change of heart revealed by the inclusion of a “Fort Henry Mall No No No” bumper sticker and other materials.

-Allen Dieterich-Ward, January 4, 2016

Notes and Sources

1 Harry Hamm, Rebirth of Wheeling: A Series of Ten Articles Reprinted from the Wheeling News-Register, July 1956; Harry Hamm, The Conference Story, c. 1957. Both in Box 1, Harry Hamm Papers, OCPL.

2 Hamm, “The Conference Story”; Mary Chilton Chapman, “Anti-Smoke Law Studied by Wheeling,”Charleston Gazette, January 14, 1955; John B. Hunter II, Marine Memories, interview by Carrie Noble-Kline and Steven W. Franklin, June 7, 1994, Wheeling Area Historical Database, OCPL.

3 Wheeling Area Conference on Community Development, Report of the Parking and Traffic Committee to the Wheeling Area Conference on Community Development, June 1954, Box 1, Harry Hamm Papers; “’Live on the Hills and Work in the City’ is Credo of Wheeling Planning Group,”Wheeling Intelligencer, Dec. 25, 1962; Ellis Dungan, dir., Wheels to Progress (Wheeling: Ellis Dungan Productions, 1959).

4 Wheeling Area Conference on Community Development, Inc., Francis Dodd McHugh,and Fred Utevsky, Plan of Future Land-Use, May 1957, Box 1, Robert L. Levenson Papers, OCPL. “Enlarged Business District Seen Here,” Wheeling Intelligencer, Oct. 25, 1956; “Redevelopment Plan Approval Awaited,” “Planning Commission Takes Active Role in ‘Forward Wheeling,’” and Jones, “Past President’s Report,” all in Highlights on Community Progress, April 1957; Urban Renewal Authority of Wheeling, “Fact Sheet on Center Wheeling Development Project,” c. 1959. All materials are from “Wheeling City Planning” Folder, Vertical File, OCPL. Darlene Stradwick, “Growing Up as One of 13 Kids: Entrenched Values,” interview by Carrie Nobel Kline and Michael Nobel Kline, May 16, 1994, Wheeling Area Historical Database, OCPL.

5 “Fact Sheet on Center Wheeling Redevelopment Project”; “Light Industrial District Urged for Center Wheeling,” Wheeling News Register, Jan. 2, 1957, “Wheeling City Planning” Folder, Vertical File, OCPL; “Our Hats Are Off,” editorial [reprinted from the Wheeling News-Register], Morgantown Post, Aug. 13, 1960; Urban Renewal Authority of Wheeling, “Land for Sale… For Light Industrial Use Located Near Business District,” advertisement, Charleston Gazette-Mail, June 9, 1963.