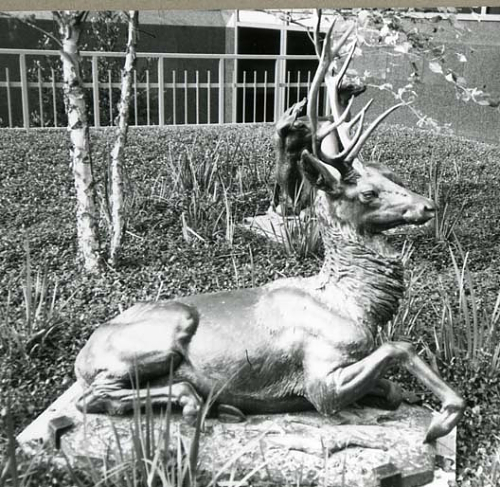

Every time I visit “The Stag” at Oglebay Park, I wonder how many Ohio Valley children have perched themselves on his smooth, verdigris surface. How many families have spread a picnic blanket in his shadow on a warm summer Sunday while the band plays on at the Anne Kuchinka Amphitheater? How many West Virginia winters has he endured, stoic and ever ready to please another visitor who stumbles upon his majestic form permanently poised atop his redbrick pedestal?

Most of us Oglebay Park fans know “The Stag” well. His oxidized-green hide and noble face serve as icons for a place we love. Yet, few people know the history of this marvelous bronze sculpture. Although there are many stories about “The Stag” that seem fitting for a much-loved community artifact, it took quite a bit of research to uncover his story, and regrettably, some questions remain unanswered.

“The Stag,” as the sculpture is formally known, sits atop its base in a field near the Oglebay Mansion Museum. Visitors can find the statue by following the red brick path past the Mansion, walking through the gates, and onto an asphalt walking path that runs around the statue and down to the upper lake.

According to The Smithsonian and Oglebay records, “The Stag” is made of bronze, was sculpted by Anna Hyatt Huntington, and has been in the park since before World War II. Beyond that, not much is known about how, why, or even who acquired it. It has been speculated that it was given to Oglebay as part of a commission of animal sculptures created by the artist for each of the 50 states. However, Jennifer Page, library assistant at the Library and Research Center at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, told me that she “…is unable to confirm or deny Mrs. Huntington created sculptures for each state.” This debate represents just one of the many unresolved mysteries surrounding our beloved friend.

Despite my efforts and the efforts of many others, the exact date and reason of acquisition remain unknown. Given that the statue was sculpted in 1929, and the city of Wheeling accepted Col. Earl W. Oglebay’s bequest to maintain his land as a public park in 1928, it seems likely, but not impossible, that “The Stag” was either purchased or given to the park and not to the Oglebay family as some fans believe.

A World-Renowned Artist

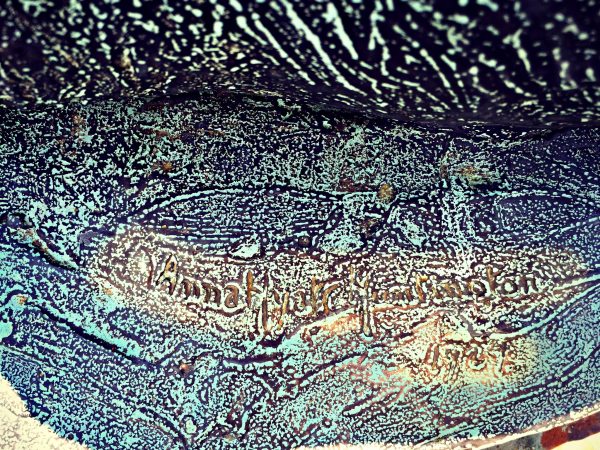

Despite the murkiness surrounding the arrival of “The Stag” at Oglebay, a great deal is known about the sculptor, Anna Hyatt Huntington. Although her name is carved on the base of the statue, it is not easy to read because of years of weathering. In fact, many people familiar with the history of Oglebay Park falsely assume that the signature is of a Waddington, which makes some sense given that the land was once called Waddington Farm.

Upon further inspection and armed with foresight, though, Huntington’s name seems obvious. As the sculptor of more than 500 pieces, her signature festoons art all over the world. When I learned of her contributions to the art world, I was stunned to realize that we have one of her works right here in Wheeling, hidden in plain sight.

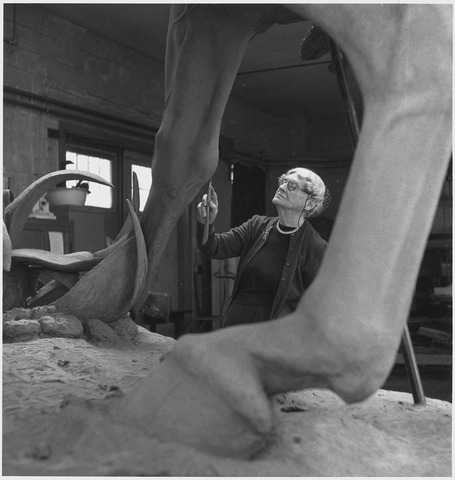

Anna Vaughn Hyatt was born in 1876 in Cambridge, Mass., to a well-educated family, who greatly contributed to her career trajectory. Her father, Alpheus Hyatt, was a professor of paleontology and zoology at Harvard University and MIT, which contributed to her great interest in animals—the subject matter for much of her work. In addition, her mother, Aduella Beebe Hyatt, was an amateur landscape artist, and her sister was a sculptor, though much lesser known than Hyatt Huntington would later become.

Although she spent a few years studying art formally, including with the illustrious Gutzon Borglum, the designer of Mount Rushmore, she left art school to conduct her own studies of animals in zoos and circuses. She was dedicated to depicting animals realistically and with emotional expressions—features she became known for throughout her career. In fact, she first earned international acclaim in 1900 for her 40 animal sculptures on exhibit at the Boston Arts Club.

In 1910 Hyatt Huntington was awarded an honorable mention in an exhibit in Paris for her life-size statue of Joan of Arc, which earned her a commission from New York City to create a bronze version of the statue in honor of St. Joan’s 500th birthday. When the statue was installed at the intersection of Riverside Drive and 93rd Street in Manhattan in 1915, it became the first public monument in New York City created by a woman and the city’s first statue dedicated to a historical woman.

In 1923 she met and married Archer Milton Huntington, heir to the Huntington railroad empire, who also has ties to Oglebay Park. The Good Zoo train is a Huntington train, according to John Hargleroad, director of operations at Oglebay Park. In addition, the city of Huntington, W. Va., is named after Archer’s step-father, Collis P. Huntington.

In 1927 Hyatt Huntington contracted tuberculosis from which she suffered for the next decade. Although the disease dramatically slowed down her work, it did not stop it. As Hyatt Huntington says in an oral interview conducted in 1964 by Dorothy Seckler for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution: “Well, the reason for that prolonged period of TB was that I wouldn’t stop work. I kept doing fairly good-sized things all during that period.”

Fact, Fiction, and Somewhere in Between

Just a few years after she was stricken with TB, she sculpted “The Stag” that rests in Oglebay Park. It may be her illness that gave rise to one of the more interesting stories about the sculpture. People have said that his antlers are broken and he appears to be struggling to get up because he is ill. Another story circulating the Valley suggests that the statue represents sick or dying children, which has led some locals to wonder if somehow the story of a real-life sick child, Philip Mayer Good, might have encouraged this telling. The Oglebay Good Zoo is named in honor of Philip, who died at age 7 in 1977, and “The Stag” nearly overlooks the zoo from its hilltop perch.

Although many park employees and locals affectionately refer to the sculpture as Bambi, including Debby Koegler, who has had family events in the same field, it is pretty clear that “The Stag” was a stag from the start. As can be seen from photos taken in May 2015, repair attempts have been made on what remains of the sculpture’s antlers. Screws and other hardware were used to either re-attach pieces of the antlers or to hold what remains of them in place to resist further breakage.

It is not known when the statue was damaged, but Bill Koegler, a former golf caddy at the park, remembers that they were missing as early as 1963, which would explain why the bolts and other hardware have a similar shade patina as the rest of the statue. In addition, the Smithsonian’s May 1992 report on the condition of “The Stag” as “needs treatment” supports Koegler’s memory that the antlers have likely been broken for quite awhile. Cathy Voellinger, executive assistant at The Oglebay Foundation, confirms that “the broken antlers were a result of vandalism.”

In addition to vandalism, there have been documented instances of “The Stag” being turned on its base over the years. Although it is not possible today without a crane and other heavy machinery, Hargleroad says, “The piece used to be loose on its base and has been positioned in both direction. We don’t know which way it was intended to face.” Today, it is facing North.

The Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Inventories of American Painting and Sculpture database lists “The Stag” as being sculpted in 1929, and “Park personnel remember the statue as being in the park since before World War II.” In the same year, Hyatt Huntington sculpted at least three other stags that look quite a bit like the one at Oglebay, the most interesting of which is in a Smithsonian Inventories Record from Houston, Texas, which includes photographs of what the record refers to as The Red Deer: “The Red Deer was executed in 1929, and the Red Doe with Fawn was executed in 1934. Both are gifts of the artist to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in 1934.” This annotation introduces the possibility that Oglebay’s stag was given to the park by the artist.

Regrettably, there is no evidence of such a bequest in any records to which I have been given access. Nonetheless, it is unlikely that the Park purchased the statue, given that in the early days the Wheeling Park Commission had no money for such an investment. In addition, if the Oglebay family had owned the sculpture at one point, then a record of it would be in the archives at the Oglebay Institute, but Hargleroad states that it is not listed in their collection.

An additional point of interest revealed during my research for similar statues concerns “The Stag”‘s family. In addition to the Houston stag, another stag is poised at Audubon Terrace in New York City. Like the Houston stag, the Audubon Terrace stag has a family with him, which include a doe and her fawn. Of course, this makes me wonder what happened to the second sculpture. The Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. has a “Red Doe and Fawn” that seem identical to the Houston and Audubon statues. They were given to the Smithsonian in 1934 by the artist. Maybe this is the Oglebay stag’s family?

The Purpose of Art

In 1930 Hyatt Hunting and her husband purchased approximately 7,000 acres of former plantation land near Myrtle Beach, S. C. The weather conditions afforded Hyatt Huntington a warm place to recuperate from TB and to continue working. The grounds were christened Brookgreen Gardens and were opened to the public in 1932. It quickly earned recognition as the first modern American sculpture garden, featuring many of Hyatt Huntington’s own works, as well as hundreds of sculptures by artists from all over the world. The Gardens continue to thrive and welcome thousands of visitors each year. (Emails and phone calls to Brookgreen Gardens for information about “The Stag” have not been returned. A “Red Doe and Fawn” statue similar to the ones in Houston, New York City, and Washington, D.C., appears in Brookgreen Garden’s online collections, but the pair appears to be smaller than the others.)

In the same year Brookgreen Gardens opened its doors, Hyatt Huntington became the first woman artist to be elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters, one of dozens of awards she received over her more than 80-year career. She and her husband Archer continued to fund cultural and artistic endeavors until his death in 1955. After becoming a widow, Hyatt Huntington returned to her work with gusto and continued until a few years before her death in 1973 at age ninety-seven.

It is hard to say what Hyatt Huntington would have thought about the way in which her art is displayed at Oglebay Park. To be sure, it was intended to be exhibited outside, but would she have been aghast to know that children and their families take turns climbing the base and sitting on “The Stag”s back? Would she be horrified to learn that “The Stag” has been present at events ranging from wedding receptions to carnivals?

From my perspective, as an artist who works with words instead of bronze, I would hope that she would be pleased to find her art so well loved. As Hyatt Huntington says in her oral history interview with Seckler: “I feel the animal. I think it’s all in knowing your animal and knowing how they act and being able to sort of feel it yourself.” Oglebay Park visitors who have had the pleasure of looking in “The Stag”’s face can certainly feel Hyatt Huntington’s talents brought to life and more. They can hug his ruffled mane, place their hands in the crook of his bent front leg, and whisper their secret wishes in his long ears.

When I first set off on this quest to find out more about “The Stag,” I had hoped somehow that I could drum up interest in getting a plaque to explain his origins. Now that I have had more time to ponder his purpose, I have changed my mind. The placement of a marker might encourage more surveillance of “The Stag” or for park visitors to see the sculpture as untouchable or not part of the fabric of life in the Valley.

To me, such measures would work against the power of art. Just like “Madonna of the Trail,” the “Mingo Indian,” and the new sculptures taking up residence near Heritage Port, we can relate to each other through art. “The Stag” has become more than a priceless heirloom of generations gone by. It is a cultural artifact that tells us all where we are in the world. Just as other landmarks guide us home, “The Stag” reminds us that we are at Oglebay Park. We are in Wheeling. We are home.

For more information about the artist, see the Anna Hyatt Huntington Papers and Special Collections Research Center located at the Syracuse University Library in New York.