(written with Rebecca Taylor)

As a girl growing up in 1980’s Moundsville, West Virginia, my* teachers must have taken me and my classmates on tours of the Mound and its museum more than a half a dozen times during my school years. In fact, we went so often that I can still rattle off its claim to fame in less than a second: the Grave Creek Mound is one of the largest conical American Indian burial mounds east of the Mississippi River. Although most kids got tired of the same old 69 feet climb to the top and daring each other to touch the claw of the giant bear that stood along the museum’s back wall, I never lost my fascination with Moundsville’s most historic landmark, and it turns out, neither have many other people from around the globe.

A Brief History of the Mound

Built in stages over hundreds of years by people of the Adena Indian culture (250-150 BC), the Mound was first discovered by European settlers in around 1770 when Joseph Tomlinson, who later founded the city of Moundsville, spotted it while hunting deer. Although the Mound is hard to miss these days, back then the area was heavily wooded. Tomlinson realized that the Mound wasn’t just another hill when he was able to walk fully around the structure. Not long after his discovery, he built a cabin just 300 feet away from the Mound and gradually other settlers found their way to his valley settlement along the Ohio River.

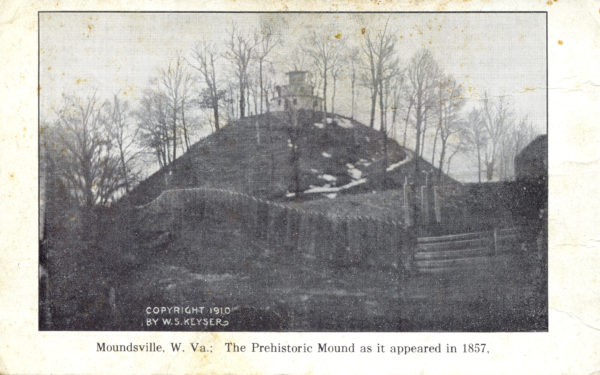

Since its discovery by Tomlinson, the Mound has undergone many different transformations. At one point, a saloon was perched atop the sacred mass. At other times, it was decorated for Christmas with lights and all the trimmings. In the early part of the twentieth century, the Mound was slated for demolition, but it was gratefully saved by the Wheeling Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Not long after, the state of West Virginia purchased the grounds, and the warden of the West Virginia State Penitentiary, which is right across the street from the Mound, was charged with caring for its upkeep for many years. The Mound became a National Historic Landmark in 1964.

The earliest known photo taken of the Mound. Abelard Tomlinson described the structure: “Upon the top of the mound, and directly over the rotunda, we have erected a three-story frame building which we call an observatory. The lower story is 32 feet in diameter, the second story is 26 feet, and the upper story ten.”

I have remained curious about the Mound since childhood. I wondered what it must have been like to tour the inside of the Mound when it was a museum back in the 1830s. I wondered why people would desecrate a burial site. I wondered where the people of the Adena culture found those 500 sea shells unearthed in one of the burial vaults. My interest was no doubt further stoked by my grandmother, Jean Burgy, who told me stories about the Mound that had been passed on to her. The story of the Grave Creek Stone remains a favorite of mine and my college students.

Real or Fake?

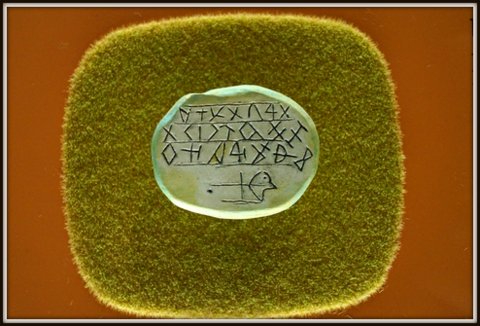

The Mound underwent its first excavation by a group of local men in 1838. Led by Abelard and Jesse Tomlinson, descendants of Joseph Tomlinson, the workers unearthed many different artifacts, including handmade jewelry, skeletal remains, and allegedly a small stone tablet. The Grave Creek Stone, as it has come to be known, was said to have been found in one of the Mound’s burial vaults. One side contained an inscription in a still unverified language. The Stone first came to the broader public’s attention when an article about it was published in The Cincinnati Enquirer in 1839. No one could have imagined then that a sandstone disc measuring at just 1 7/8 inches by 1 ½ inches would lead to more than 150 years of international speculation and intrigue that begins before the Stone was even hauled out of the Mound.

Differing accounts of its discovery have led many to denounce the Stone as a forgery. As recently as 2008, David Oestreicher argued that a Wheeling doctor, James W. Clemens, may have inscribed the Stone in his garage, where he was known to have the machinery necessary to do so. Others argue that it is authentic.

In 2016 experts tend to agree that the Stone is a hoax, but among those scholars who do believe that the message was created by an ancient civilization, there is no consensus on what the Stone says, who wrote it, or when. The speculations have been as diverse as a Viking Christmas message to a note from aliens.

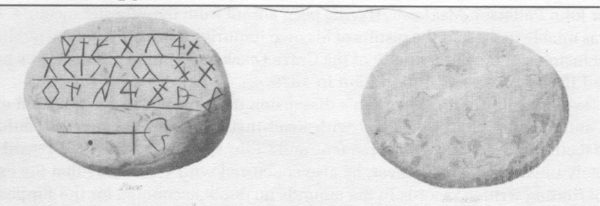

Photocopy of Seth Eastman drawing of Grave Creek Stone from Henry R. Schoolcraft’s book, Indian Tribes of the United States (1850).

The real mystery, at least for me growing up, is the current location of the Stone. As a child, I was told that the Smithsonian borrowed the Stone to study it but never gave it back. Everyone who heard that rumor wondered: Why would they take it? Does the message change history? Do they just not care about West Virginia? According to a 1909 letter sent to J. D. Shaw, editor of the Moundsville Echo, from Wills de Hass, “The tablet was deposited temporarily in the Smithsonian Institute where casts were made of wax, plaster, etc. and generally distributed.” De Hass was a nationally known antiquarian and one-time resident of Moundsville. In an 1877 letter to researcher P. P. Cherry de Hass states, “The tablet forms part of my large and valuable collection.”

The Stone’s last known whereabouts was in the collection of E. H. Davis, an American archaeologist and physician, who worked with E. G. Squire to research and write Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley. By the time he died in 1888, Davis had amassed the largest collection of burial mound relics in the United States. His collection was later given to the Blackmore Museum in Salisbury, UK, who then sold it to the British Museum in 1931. According to a 1989 inquiry by Ohio State University Professor J. Huston McCulloch, the British Museum’s North American Ethnographic Collection is not in possession of the Stone.

Cracking the Code

The riddle of the Stone’s inscription is even more captivating. Archaeologists, linguists, and other high profile professionals have offered a wide variety of interpretations as to the date of the inscription and its meaning. Given that no one currently living has seen the Stone in person, most scholars have been working with a flawed copy of the inscription. McCulloch confirms this by noting that some of the casts are not accurate impressions; therefore, it is no surprise that several interpretations were inaccurate. McCulloch, who has personally viewed the Smithsonian casts and a wax impression in the National Anthropological Archives, argues that the drawing by Seth Eastman, which appeared in Henry R. Schoolcraft’s 1850 Indian Tribes of the United States, is the only reliable drawing of the Stone beyond his own.

A drawing of the Grave Creek Stone created by J. Huston McCulloch, professor of economics at Ohio State University, after he viewed the plaster cast and wax impression housed at the Smithsonian.

In fact, the limited ideologies of some of the academics who have studied the Stone have radically impacted the way it is understood to the present day. Charles Whittlesey, a prominent soldier, attorney, and scholar, condemned the Stone to its modern day position as a forgery first in “Archaeological Frauds” in 1876 and then again in 1879 in “The Grave Creek Inscribed Stone.” In the latter piece he argues that since the markings on the Stone are not alphabetical and are not recognizable as any known symbolic language, “It is therefore of small consequence whether the stone is antique or modern, whether it is genuine or a fraud.” Whittlesey’s words proved to be the death knell for the Stone, and scholars who believed the Stone to be authentic were chastised by their colleagues. Indeed, it is widely agreed that Wills de Hass was demoted from his job as head of the Smithsonian Bureau of Ethnology’s Mound Survey project because of his well-known support of the authenticity of the Stone.

Since then the Stone has drifted in and out of scholarly and lay conversations with mostly amateur archaeologists following the trail. Some interpretations of the inscription have included the late Barry Fell’s 1976 argument inAmerica B.C.:

The mound raised-on-high for Tasach

This tile

(His) queen caused-to-be-made.

Fell claims that the script is Iberian and the language Punic, which were known to scholars at the time the Stone was discovered but not well understood.

In the early 1980s Ida Jane Gallgher re-ignited the debate about the Stone by drawing heavily on Fell’s interpretation for her article in Wonderful West Virginia, which was roundly rebuked by a number of experts, including Daniel B. Fowler, former West Virginia state archaeologist. Fowler told John Morgan of the Charleston Gazette, “modern archaeologists simply don’t accept the stone as authentic.”

Wills de Hass sent or delivered the Grave Creek Stone to the Smithsonian, where a plaster cast and wax impression were made of the Stone. The Smithsonian has said that the Stone itself has never been part of their collection.

The debate has made its way into the twenty-first century. B. L. Freeborn, author of The Deep Mystery: The Day the Pole Moved, proposes that the stone’s inscription offers proof that the Grave Creek Mound was not constructed arbitrarily. He argues that the lines on the stone are not guidelines but symbolic representations of longitude and latitude points. Freeborn’s article breaks down the mathematical numbers and concludes that while many believe North American natives did not understand how to measure locations until Europeans taught them, the inscription may prove otherwise. Freeborn believes that the inscription suggests “an awareness of Greenwich, England and its zero significance.”

Freeborn continues by highlighting similarities between the latitudes and longitudes of the Grave Creek Mound and the Miamisburg Mound located in Dayton, Ohio. Additionally, there are references to the possible correlation between the Grave Creek Stone and ancient inscriptions like the Kerbstone 86 from Knowth, Ireland and the Metcalf Stone found in Georgia. Freeborn argues that by rotating the stone into a vertical position the inscriptions can take on a new meaning. He believes that this is where previous scholars have been neglectful and notes that most scholars assumed the lines on the stone to be “guides for writing, such as ruled school paper.” However, because not all present-day cultures read left to right, it seems Freeborn is very wise to address the potential bias in assuming the stone is to be read in a linear fashion. Incidentally, most of the scholars that have researched the stone’s inscriptions were accustomed to reading left to right; therefore, to encounter this bias, while unscientific, is somewhat understandable. Freeborn’s theory concludes by suggesting that the inscription honors the event of the “separation of the North Pole from Magnetic North” and believes there may be a strong link between the Grave Creek Stone, other mound positions, and ancient writings. While Freeborn does not offer significant scientific studies to support these theories, the uniqueness of the theories may be worth a thorough study if supported by members of the scientific community.

In complete opposition to Freeborn, amateur linguist Stuart Harris rejects the idea that the Grave Creek Stone’s inscription has an origin of European ancestry (or European ancestry as it is known today). Instead, Harris re-examines a theory proposed by Edme-Francois Jomard, a respected French geographer/linguist, and William G. Hodgson, former employee of the US Consul of Tunis, made in the mid-1800’s.

Jomard and Hodgson believed the stone’s inscription to be very similar to the writings found in “Algiers, Tunis, and [the] African interior.” Jomard attempted to illustrate the similarities between the Grave Creek Stone and Libyan writing by using samples from the ancient monument at Dougga as well as alphabetic characters in Libyan and Numidian. Jomard believed it very possible that an African ship could have brought crew members “forty degrees north latitude and that one of its lost voyagers” could have found their way to be buried inside the Grave Creek Mound, citing that the exotic language, dress, and culture would have made that crew member an “extraordinary personage and one worthy of ceremonial burial.”

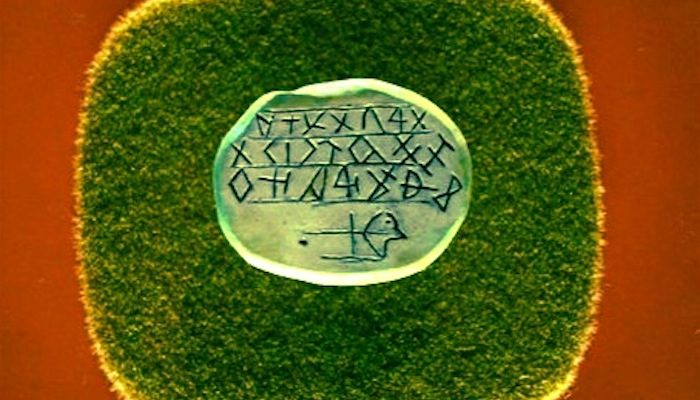

An artistic rendering of the Grave Creek Stone on display at the Grave Creek Mound and Archaeological Complex in Moundsville, West Virginia. Photo courtesy of Rebecca Taylor.

Interestingly, this idea of a Libyan origin for the Grave Creek Stone has found its way back into recent theories. Stuart Harris undoubtedly believes that the “Grave Creek Stone is the real thing” and that its origins can be traced to a Libyan soldier/sailor who would have traveled on a Carthagean fleet and landed in Ohio sometime around 400BC. Harris explains that before the 1950’s (when the majority of investigations were performed on the stone) the world did not know about the syllabary script of Libyan (discovered by Marija Gimbutas), and incidentally, it was not until 2010 that the script was understood “when two hundred Scandinavian bilinguals were recognized.”

Therefore, Harris proposes a language based in Old European and terms it as “Finnish without a dialect.” The script reads left to right and top to bottom. He believes this is the base language for the Grave Creek Stone with the addition of ruled lines (something that pure Old European did not use but was more common with Mauritanians of Libya).

Harris believes a man who called himself Champion inscribed the stone as a type of diary. Apparently, the man’s name is revealed through the long-sword picture on the stone. Harris provides the following translation:

Lovely champion created the best family. I think of a wife far away in a

meadow, or a woman also at night, naked in a small cabin. Now the storm of

storms struck us. It created grief, wrecked everything somewhat, started a battle

among wretched men. [Long sword] I make many great champions.

Is it possible that, like Jomard’s beliefs, a storm could have carried a ship filled with African crew members off course to North America? And could it be possible that members of the crew were taken as captives by the natives or even honored as god-like beings as Jomard suggested? Although possible, these ideas still leave questions regarding how a shipwrecked crew could have been transported from the coast to the inland areas of the Ohio Valley.

Harris cites the Jade Disk found in an Adena mound in Kentucky as having a possible relation to the Grave Creek Stone due to its similar translations. Like Freeborn’s theory, Harris offers an intriguing theory to the mystery of the Grave Creek Stone, but the support for the argument is limited. Nonetheless, if there are findings surrounding Libyan script that are as recent as 2010, it could be of interest to the linguistic community to do a scientific follow up on Harris’ theory. Additionally, this could be an interesting platform for today’s historians to consider the timeline of Libyan fleets and the possibility for these fleets to find their way onto North American soil.

Interestingly, the idea that the inscription could be a blend of languages does not seem to be something scholars have considered. However, famed archaeologist Henry Schoolcraft, one of the first scholars to investigate the stone, did believe the stone to have alphabetic ties to the following languages: Celtic, Etruscan, Ancient Greek, Runic, Gallic, Old Erse, Phoenician, Anglo-Saxon, and Appalachian. Nonetheless, Schoolcraft’s conclusion about the stone’s origin still held a primary origin—Celtic ancestry. In fact, Harris’ theories about the Stone parallel Schoolcraft’s assertions in other ways. For example, Schoolcraft said, “[The stone] has belonged to some adventurer, or captive carried by tribes to this spot.” While differing on the land of origin, this idea closely coincides with Harris’ assessment that the inscriber was a type of solider. Schoolcraft, like Harris, also believed that the large picture of a sword suggested military achievement.

Agreeing to Disagree

How could so many scholars be in disagreement? It is possible that the single origin scholars are looking for may not exist—not because it is inauthentic, but because the inscription could be a hybrid of languages perhaps pieced together by someone who was a prisoner or merchant—someone exposed to multiple languages? If the linguistic theory of Proto Indo European (PIE) is true, languages are all essentially derived from the same source. Additionally, it is understood that languages were often derived from the hybrid-like influence of two languages interacting with each other. Therefore, the possibility of a traveler having a background with multiple languages is highly likely.

The Mound as it stands today. Photo courtesy of Kelly Fleming Shrader.

Nothing involving the Grave Creek Stone leads to answers that are all black or all white, and the fact that the original Grave Creek Stone has been lost to time leaves some scholars to remain skeptical about its authenticity. But that is what is so exciting about the Stone. It leaves the door open for more research and debate. As the philologist David H. Kelly writes, “My major point, however, is not to argue that the inscriptions are, indeed, genuine, but rather that I do not find it fantastic to think that they may be.” In other words, there remains room for considerable work to be done on the mystery of the Grave Creek Stone. At the very least, we should endeavor to find it.

The Grave Creek Mound continues to turn a spotlight on Moundsville, West Virginia and the whole of the Ohio Valley. It is soon to be featured in a PBS special, which will include a recent investigation into the Mound involving geophysical remote sensing technology.

You can visit the Grave Creek Mound Archaeological Complex to see an artist’s rendition of the Stone and to learn more about its timeline. Admission is free, and the grounds are open Tuesday through Friday from 9 am-5 pm. The view from the top of the Mound is worth the effort of the climb.

*All first person references in this article are attributed to Christina Fisanick Greer.

Click to read more from the author here: ChristinaFisanickGreer.com.

This story originially appeared on Vandaleer.com.