It rests in plain sight but most Wheeling area residents are not aware the Manchester neighborhood still sits secluded on land across Big Wheeling Creek and at the base of the hill where a portion of the village Bethlehem is located.

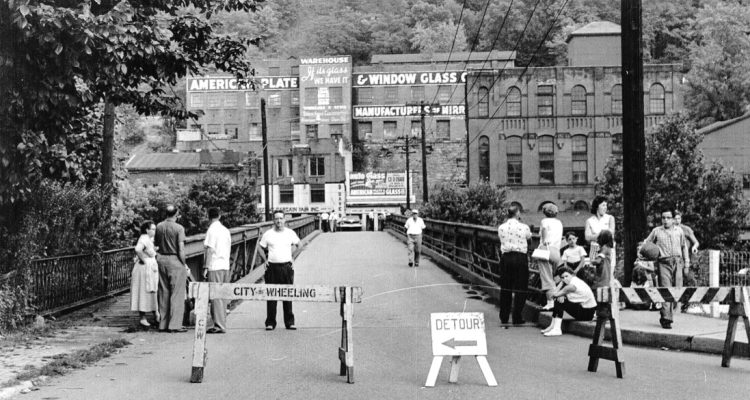

There has been only one legal way in and out of Manchester, though, since the mid 1990s because that is when the city of Wheeling removed the bridge that spanned the tributary to the Ohio River. The city at the time, according to Del. Erikka Storch, insisted the Manchester Bridge would be reconstructed, but the sandstone abutments are still without a span to support.

“I started working with him in 1992 and was there until 2014 and I really didn’t hear anything more about it. Honestly, this is the first time anyone has ever asked anything about it and I think that’s because that bridge has been gone for about 30 years and today’s residents don’t even know it’s there even though they see it when driving on (W.Va. Route 2),” Storch said. “There was never any activity in the area and no one ever asked any questions about it. I did see some people who would park there so they could take naps during the day. They used it as a hiding place, I guess, and I never did see any of those people get interrupted, but as the Chamber president, no one has said a word, and as a Delegate, it’s never come up as a topic.”

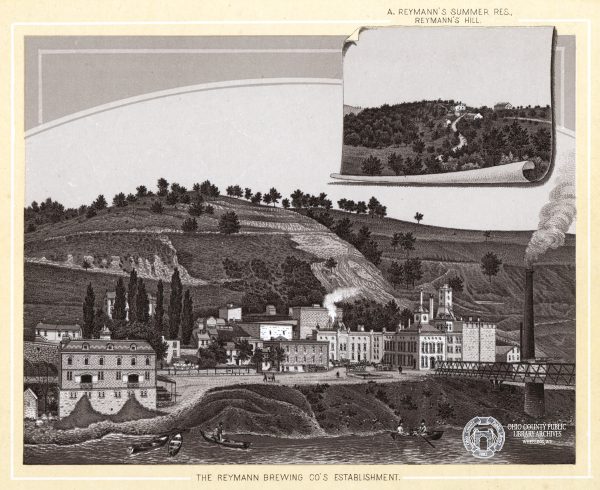

The area is referred to as “Manchester” in the 1873 Atlas, explained local historian Ryan Stanton, a history teacher at Wheeling Park High School. Stanton has conducted a tremendous amount of research in the city’ brewing history and the Reymann Brewery was located in this area.

“It was named that because of a previous property owner, and it just stuck,” he explained. “I think the area has been forgotten by most people in the city and you can tell that when you go there. In my opinion it was a strange decision for the city to remove the bridge and not replace it because, without the bridge it’s abandoned.

“It’s difficult for me to explain it to my students because there’s not much that’s ever been said about it,” Stanton continued. “My students see it because now they know it’s there, but they have a tough time imagining why that area is the way it is today.”

History of this Hood

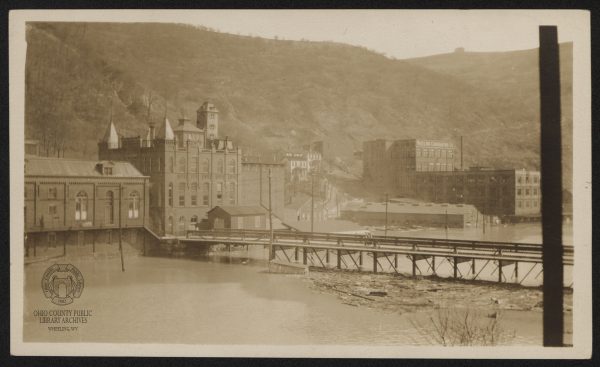

Beer brewing was big business in the city of Wheeling until prohibition was implemented by the West Virginia Legislature in 1914, and the Manchester area was a popular one because of the natural water springs in the area and the hillside which could be mined for coal.

According to information posted online by the Ohio County Public Library, no one truly knows who brewed the very first beer in the Friendly City.

“To historically review the dawn or subsequent development of man’s appreciation for ale and beer, would be no sinecure achievement, suffice it to say that since the arrival of the earliest pioneers in this section, brewing, in some shape, has ever held its own. But the nutritious and palatable blending of malt and hops found little difficulty in fascinating the popular taste, even our grand-fathers were free to extol the merits of “John Barleycorn.” We cannot, with any degree of certainty, venture an opinion as to who brewed the first ale in this section, but believe we are not far out of the way in saying that Mr. P. P. Beck, founder of Reymann’s brewery, was the first beer brewer here, and Mr. Louis Keller was the pioneer saloonist who dispensed it at retail, in a humble premises, located at the southern end of the creek bridge. Upon the introduction, hereabouts, of the famous lager, the Germans took no small degree of pleasure in renewing their old acquaintance with it, but it took the American born some little time to school the appetite, which however, we may be pardoned for suggesting, is to-day tutored to a degree of average perfection. The faculty and invalids, alike, now proclaim, in many instances, that ale stands unrivalled as a tonic, while he who sips more as a matter of enjoyment, considers beer to be amply “headifying” for him. We therefore draw the inference that a brief sketch of our local brewing interests will be acceptable and duly appreciated all round.”

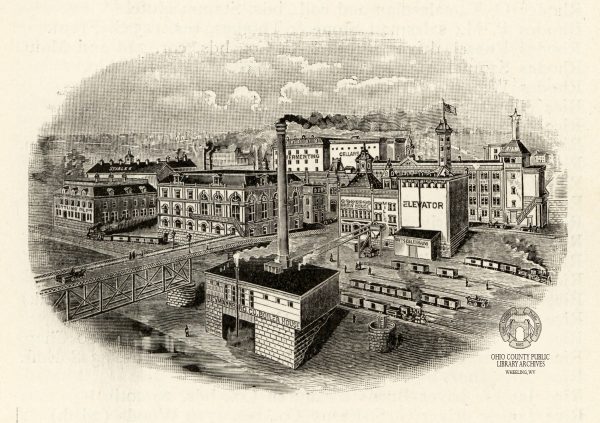

Butterfield’s Malt House was in Center Wheeling, Smith’s Ale Brewery did business in East Wheeling, and The Eagle Ale Brewery manufactured in downtown near Independence Hall. The Schmulbach Brewery, which still stands today in South Wheeling, was one of the most popular ales in Wheeling by the late 1800s, and the Nail City Brewery brand was even bottled by the Siebke’s Bottling Department and sold in the downtown district.

The Reymann Brewing Company was founded as the P.P. Beck Brewery in 1849 and George Reymann gained full ownership by 1863 in the Manchester area. It was situated near the old Catholic cemetery where cast iron coffins were discovered when the interred souls were interrupted to make way for I-70, and that area, too, rests in ruins today.

From J. H. Newton. History of the Pan-Handle, Wheeling, J.A. Caldwell, 1879:

“The Reymann Brewery, located on the banks of Wheeling creek, in the east end of the city, was first put into operation in 1849, but was only succeeded to by its present proprietor in 1865, since when neither pains nor expense have been spared in perfecting its productions and its facilities; hence, in magnitude, this still stands the lion institution of its kind in West Virginia. The front view of the building is an imposing specimen of architecture, in brick and stone, extending three hundred and sixty feet along the front, being three and four stories high to meet the requirements of several departments. The premises stand at the base of a huge hill, and are favored with the advantages of an ample supply of the purest spring water, coal workings almost adjacent, and only a short distance from river and railroad facilities to all parts. The interior of the brewery is a model of a system, and is appointed with every desirable modern facility yet discovered in the art of brewing. The magnificent cellar accommodation is also a special feature. The cool, dark cells extend into the hill hundreds of feet, are perfect vaults in solid, dry and impervious rock, being lofty, well ventilated and throughout fitted regardless of expense, with cold air pipes running from a mammoth freezer, constructed at an immense cost, and by which an evenness of temperature is maintained, or if desired, in the very height of summer, from 38 to 40 degrees can be kept with ease. The united capacity of the cellars we could hardly estimate, but the firm usually keeps from 7,000 to 8,000 barrels on hand through the summer, while their annual product may be estimated at 13,000 barrels. A fine brick-built bottling works is also conducted near by, and through the summer Reymann’s famous beer is put up in glass to an enormous extent, for family consumption as well as restaurant purposes. The extensive business conducted at this brewery is a high compliment to its enterprising and popular proprietor, while forming an important item in Wheeling’s manufacturing resources.”

“They all were part of Wheeling’s brewing industry, and it reached its high point beginning in the 1880s, but prohibition killed them all, of course,” Stanton reported. “There was a lot of brewing that was taking place at the time the state brought in prohibition, and most of them lost everything. Reymann, though, was into a little bit of everything in this area. I’m not saying it didn’t impact that family because I’m sure it did, but from what the records indicate, it didn’t force them out of this area. They just weren’t allowed to brew their beer anymore.

“That area, though, remained a business area even after the brewery closed until that bridge was taken out by the city. The main Reymann building has been used by several other businesses over the years, but some of the buildings that were part of the brewery aren’t there any longer,” he continued. “I have to believe that if the city would have replaced the bridge, the Manchester area would still be a part of the city, but now it’s just there, and no one seems to know it.”

Storch remembered her lunches at Rosalie’s Bar & Grill that was located on the street level of a white house about 100 yards from the fabricating factory, and there was another building where another bar was located, but it literally crumbled to the ground a little more than a decade ago.

“When I started working for my father at Ohio Valley Steel, I asked him why he had never put up a sign for the business, and he answered, ‘Who would see it?’ He was right,” Storch said. “It is forgotten Wheeling, and I worked there for more than 20 years.”

A New Manchester?

When the Manchester Bridge remained in place, residents of South, Center, and East Wheeling could travel to Wheeling Hospital by traveling 17th Street, Rock Point Road, and then Mount de Chantal Road to Medical Park with one traffic light along the way.

It was known as, “the back way to Wheeling.”

Nowadays, though, those citizens must utilize W.Va. Route 2 and Interstate 70 before reaching two traffic lights at the intersection of Washington Avenue and Mount de Chantal Road.

Another path exists adjacent to Ohio Valley Steel and another large factory, but the roadway is privately owned by the two companies and is not a legal passage for throughway traffic.

“I know there are some people who are confused about that fact, but it is true,” Storch confirmed. “Without the bridge we would have the raw materials delivered to the shop via Rock Point Road, and my father had the shop set up so everything moved forward toward delivery from that road to 20th Street.

“That’s why, if they ever did replace the bridge, it would have to be one that had a decent weight limit because it’s an industrial area,” she said. “There are some other companies down there still, and a new bridge might mean access for more housing. Who knows what could happen? Without it, though, I don’t think anything will happen there.”

Such a span would re-link residents in Morningside, Clator, and the Washington Avenue business district to the city’s downtown without a dependence on the highways that are often under repair. In fact, according to Gus Suwaid, district engineer for the state Division of Highways, access to the interchanges connecting W.Va. Route 2 North to Interstate 70 East will be limited once work begins on the three bridge systems east of Wheeling Tunnel.

“Right now there is not a timeline yet established for that work, but it’s going to take place soon because it has to,” Suwaid said. “Two of them will be renovated, and one of them, the middle one, will be completely removed and replaced so that section of interstate will be closed. We’re lucky to have I-470.”

Suwaid estimated a new span over Big Wheeling Creek in that area would cost a few million dollars but would not be a project contracted by the Division of Highways although former W.Va. Gov. Cecil Underwood (1997-2001) once promised the state would deliver a new span, according to Wheeling City Manager Bob Herron.

Wheeling Mayor Glenn Elliott said he has heard of this neighborhood and of the bridge but not because anyone has expressed an interest in developing there.

“Nobody approached me about the topic during my campaign or since becoming mayor,” Elliott explained, “but I have heard suggestions for replacing the bridge over the years before I was elected.

“In the world we live in, the need for a new ‘Manchester’ Bridge has to be weighed against other infrastructure needs facing our community,” the mayor continued. “I would need to see an assessment of the residential and commercial investment opportunities that might ensue if a bridge were to be erected.”

Herron, the Friendly City’s city manager for nearly 15 years, recently visited the Manchester area to examine the condition of Rock Point Road.

“It would be great if a new bridge was constructed there because of what it would do for traffic patterns for residents, but I believe it would be a very expensive project,” he said. “The city has worked on the two bridges that allow access to the industrial park, and those two projects have cost more than $3 million.

“There is property near the top of Rock Point Road that could potentially be conducive for a housing project, but I really haven’t heard a word about the area or the bridge for at least 12 or 13 years,” Herron added. “I do think that, without the bridge, people have changed their travel patterns, and that’s led to people forgetting about the area completely.”

(Cover Photo archived by James Thorton of Creative Impressions)