Lydia Boggs Shepherd Cruger lived and died in Wheeling during some of the most formative years in both the city’s and the country’s history. Over her remarkable 101 years, she witnessed the United States’ early development, from frontier battles with Native Americans to the Revolutionary War and even the Civil War. Known for her vivid memory and captivating storytelling, Lydia played a crucial role in preserving Wheeling’s history, giving today’s generation a glimpse into the city’s past.

The Early Years of Lydia Boggs

Born on February 26, 1766, in Berkeley County, Virginia, Lydia spent much of her childhood on the frontier. Her father, Captain William Boggs, served in Lord Dunmore’s War and was stationed at Catfish Camp, now present-day Washington, PA. His family, including Lydia, lived at the camp alongside Moses Shepherd, who would later become her husband. Eventually, both the Boggs and Shepherd families relocated to Wheeling and Fort Henry.

As a child, Lydia lived through both major sieges of Fort Henry, as well as several other attacks and raids. Her experiences during these violent conflicts shaped her later storytelling, making her a key voice in preserving Wheeling’s early history.

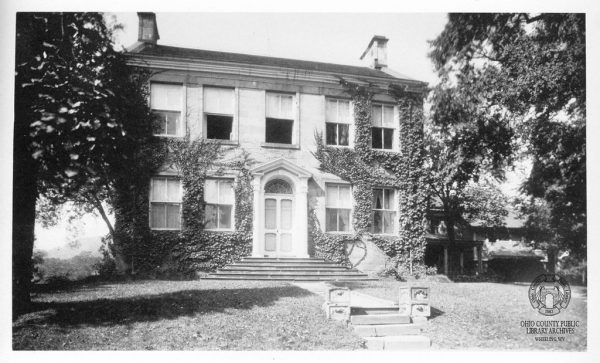

After the Revolutionary War, Lydia and her husband, Moses Shepherd, built Shepherd Hall—now known as Monument Place—on their plantation. The couple hosted some of the most influential figures in American history, including their close friend Henry Clay, as well as Presidents Andrew Jackson and James K. Polk. According to local legend, Lydia used her friendship with Clay—and her ability to hold her liquor—to persuade him to ensure that the National Road not only passed through Wheeling but directly by Shepherd Hall. In honor of Clay’s influence, the Shepherds erected a statue of him on their front lawn. Today, Shepherd Hall still stands in Elm Grove and is owned by the Osiris Shrine.

Following Moses’ death, Lydia married former New York congressman Daniel Cruger. She remained active in Washington politics, continuing to influence national conversations while maintaining her presence in Wheeling’s social and political circles.

The Sieges of Fort Henry and Frontier Attacks

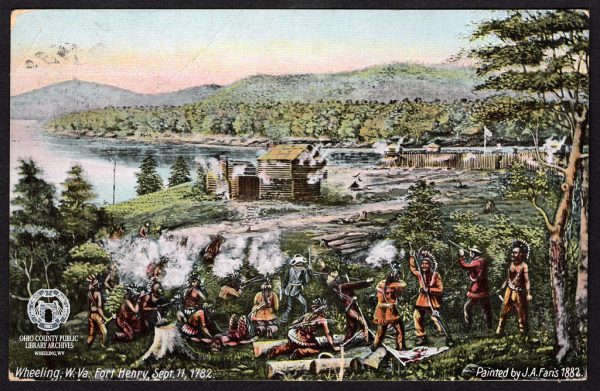

During the frontier era, Native American attacks were a frequent threat to the settlers of Wheeling. Lydia was present for both major sieges of Fort Henry, in 1777 and 1782, as well as other violent skirmishes.

The first siege in 1777 saw Native American forces attack the settlement, forcing residents to abandon their homes and seek refuge inside the fort. Their cabins were looted and burned, and it was during this battle that Samuel McColloch made his famous leap from Wheeling Hill to escape his pursuers. The aftermath of this siege also led to Foreman’s Massacre, where Lydia witnessed the brutal loss of many settlers and helped care for the wounded.

The second siege of Fort Henry in 1782 was just as deadly. By this time, the settlers had become complacent, making it easier for Native American forces to launch another attack. This battle is best remembered for Betty Zane’s legendary run to retrieve gunpowder from her brother’s nearby cabin—a feat that allowed the settlers to continue their defense. Lydia, present during the siege, later recounted the intense violence and the many casualties that followed.

Lydia’s firsthand experiences at the fort shaped her role as a storyteller, helping preserve these pivotal moments in Wheeling’s history. However, as time passed, her recollections became the subject of controversy.

The Betty Zane Controversy

Sixty-seven years after the second siege, Lydia signed an affidavit claiming that it was not Betty Zane who made the heroic run for gunpowder, but rather a woman named Molly Scott. She also asserted that the commonly accepted version of the story—where the runner traveled from the fort to the cabin and back—was incorrect. This claim stirred heated debate in Wheeling, as it challenged a long-held local legend.

While most historians continue to credit Betty Zane, some believe Lydia may have confused the events of 1782 with another attack on the fort in 1781. Regardless of the truth, Lydia’s version of events added another layer of intrigue to Wheeling’s storied past.

Later Life and Legacy

Lydia lived a bold and vibrant life well into old age. Even in her later years, she continued to host elaborate gatherings at Shepherd Hall and remained engaged in politics, frequently traveling to Washington. She was widely known for her detailed recollections of frontier life, participating in numerous interviews and contributing to books and historical records.

Her remarkable longevity and vivid storytelling provided Wheeling with invaluable firsthand accounts of its early history. Through her experiences, the city gained a deeper understanding of its role in shaping the United States. Today, Lydia Boggs Shepherd Cruger remains a compelling figure in Wheeling’s history—one whose influence continues to be felt through the stories she left behind.