Interestingly enough, Joseph Ray, a Wheeling-area man, became an integral part of educating the masses in the third “r,” arithmetic.

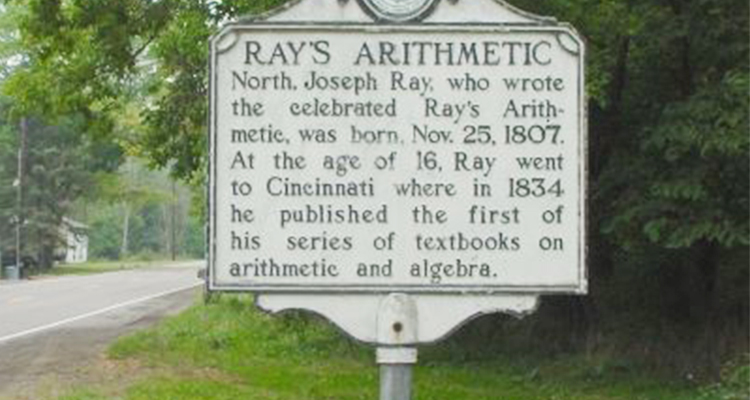

Joseph Ray was born in Ohio County, Virginia, in 1807 on a 160-acre farm his grandparents had purchased 17 years prior. The land is located in what is now Valley Grove, West Virginia, as a white historical marker proudly states. The Battle Run farmstead was just four miles from West Liberty and two miles from National Road.

Unlike his forebears, Ray was not interested in tilling fields or milking cows. He loved to read, write and how to “figure,” which, along with “ciphering,” was another word for mathematics. This passion for math led to a brilliant teaching career and the authorship of the most popular series of math texts in the country during the 19th century.

WHEN THE STUDENT BECOMES THE MASTER

Ray grew up on the family farm as the oldest of nine children. His parents, William and Margaret Graham Ray, were members of the Society of Friends (Quakers), and taught their children about the simplicity of life and the importance of hard work, principles that influenced him and his siblings throughout their lives.

In fact, one of his brothers, Thomas Ray, became a well-known abolitionist, who was led by his Christian beliefs to work toward dismantling the institution of slavery. In 1838 he was united in marriage to Julia D. Curtis by the Rev. Alexander Campbell, founder of Bethany College and the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Campbell’s nephew, Archibald, became an abolitionist and later the editor of the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, which played a significant role in the formation of the state of West Virginia. Thomas Ray died in 1886 near Decatur, Illinois, more than 30 years after his famous mathematician brother, Joseph.

Like other children on the Allegheny frontier, Joseph Ray attended school only a few months out of the year. His father recalled that Ray could read and “enumerate to hundreds of millions” before he started school at age 6. By age 15, Ray was studying algebra, geometry and surveying at local academies.

At age 16, he lit out with thousands of other Americans for the newly opened portions of the Ohio Country and began teaching school in Cincinnati. Ray saved his teaching salary and entered Ohio University in Athens. Eventually, his money ran out, and he had to drop out of school to go back to teaching. Along the way, he had been studying medicine with Dr. Joel F. Martin of Warrenton, Ohio, who paid his way through medical school at the Medical College of Ohio in Cincinnati. He graduated with his M.D. in 1831, but quickly realized that practicing medicine was not for him.

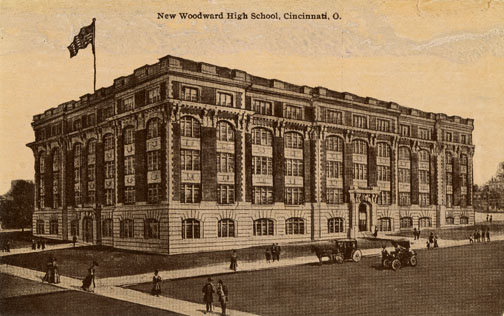

Later that year, he returned to his first love, teaching mathematics, at the newly opened Woodward High School in Cincinnati. Founded by William and Abigail Cutter Woodward, it was the first public high school west of the Allegheny Mountains. Five years later, Woodward High School became Woodward College of Cincinnati, and Ray became a professor. In 1851 the college became a high school again, and Ray served as its principal until his death from tuberculosis in 1855. (President William Howard Taft graduated from Woodward High School in 1874.)

Ray was known for his incredible productivity, which he attributed to having a set schedule. In a diary entry dated April 22, 1832, he wrote, “System is everything — let a man always rise at a certain hour (I would say five o’clock at this season of the year) and attend to his business in a certain order; have a time for every action and a place for every thing, and in this way he will accomplish enough to astonish himself.”

Ray was legendary for his playfulness and compassion as much has his hard work. He was often seen enjoying games of kickball with students and speaking with them with kindness and compassion.

FROM THEORY TO PRACTICE

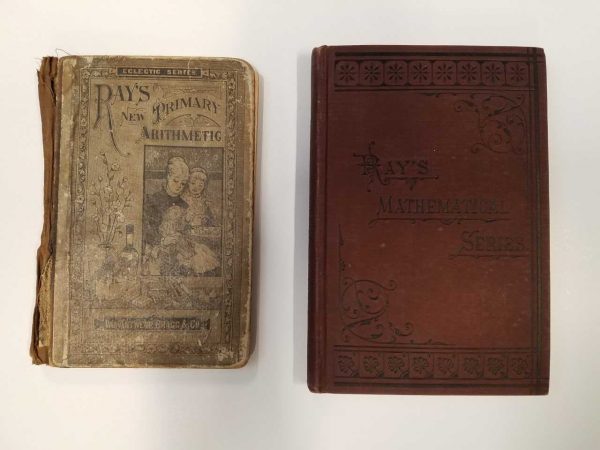

It was during those teaching years that he wrote a series of math textbooks that became the best-selling and longest-used math books well into the first quarter of the 20th century. Many titles (nearly 50, including revised editions) appeared in Ray’s math series over the years, but the main series consisted of six core books: Primary Arithmetic, Intellectual Arithmetic, Practical Arithmetic, Higher Arithmetic, Elementary Algebra and Higher Algebra.

Ray’s teaching methods were so widely popular because they took difficult theories and concepts and applied them to everyday problems, such as how to determine the weight and cost of tea, coffee and butter. Prior to Ray’s innovative lessons, math was thought to be an abstract (and boring) pursuit. In the preface to one of his books, he wrote that the purpose of his teachings was “to combine the clear explanatory methods of the French mathematicians with the practical exercises of the English and German, so that the pupil should acquire both a practical and theoretical knowledge of the subject.” A lofty pursuit indeed!

Some examples from Ray’s original textbooks include the following:

If sugar worth two and a half cents a pound, be mixed in equal quantities with sugar worth four and a half cents a pound, how many pounds of the mixture will be worth $1?

A man and his wife can drink a keg of beer in twelve days; when the man is away it lasts the woman thirty days; in what time can the man drink it alone?

HIs playfulness was obvious throughout the series, as he sometimes presented problems in poetic verse, such as this little ditty about Pythagoras’ Theorem:

A castle wall there was whose height was found

To be one hundred feet from top to ground

Against the wall the ladder stood upright

Of the same length the castle was in height.

A waggish youngster did the ladder slide

The bottom of it ten feet from the side,

Now, I would find how far the top did fall

By pulling out the ladder from the wall.

It was through this practical approach that he made math at least tolerable for many students, who informally referred to his books as simply Ray’s. At one point, Ray’s books were the best-selling textbooks across all disciplines.

In addition to teaching math and writing textbooks, Ray, along with his friend and Woodward College colleague, William Holmes McGuffey, organized the Western Literacy Institute and College of Professional Teachers to better train teachers. McGuffey, who wrote the famous McGuffey’s Readers series, was born not far from Ray in West Finley, Pennsylvania. McGuffey’s reading textbooks were eventually more popular than Ray’s Arithmetic, selling over 120 million copies between 1836 and 1960.

I AM NOT MY BROTHER’S TEACHER

Not everyone thought that Ray was a genius, though. His other brother, Moses (called Mose), who was quite a character in his own right, used to gleefully look for errors in his brother’s books. Fifteen years younger than Ray, Mose had stayed home on the family farm outside of Wheeling while his brother headed for Ohio. While Ray married Catherine Gano Burt Ray in 1831, and fathered one surviving son, Daniel Gano Ray, Mose remained single all of his life, preferring to live most of his years with only his housekeeper for company.

Mose was known for his mechanical skills and intelligence, including blacksmithing, masonry, and yes, mathematics. After having finishing reading one of his brother’s books, it is said that Mose wrote to him, “If I couldn’t write a harder book than this I wouldn’t write any.” When asked what he thought of his brother’s more advanced texts, Mose said, “Well, it is fine for a child.”

While he was criticizing his brother’s work, however, Mose spent most of his inheritance on farming inventions, which would go on to be patented by others who were more fastidious.

Having squandered his family’s fortunes and lost the farm, Mose left the Ohio Valley for New Mexico in search of gold. After suffering from cancer for many years, he died in 1890 penniless and alone. His body was never sent home to the Ohio Valley, and rumor has it (thought no records exist) that in the Dement Cemetery plot next to his parents supposedly lies his friend and namesake, Mose Tygart, instead.

The Ray’s Valley Grove home, a double log cabin, was razed in 1916. Joseph Ray and his wife and children are buried in Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati, Ohio.

RAY’S LEGACY

Although Ray’s Arithmetic series went on to be replaced by other math textbooks around the 1920s, his legacy lives on in the digital era. A growing number of homeschooling groups have re-discovered Ray’s methods and are using his books to teach their children mathematics. Although some of his books have been slightly updated to make them relevant to 21st-century learners, their simplistic, application-driven focus remains constant. In fact, there are a number of YouTube videos dedicated to teaching Ray’s methods that are based directly on his original problems from the 1830s and ’40s.

Woodward High School in Cincinnati’s Bond Hill neighborhood still stands to this day. Since 1976, though, it has been known as the School for Creative and Performing Arts, a public school offering training in dance, drama, instrumental music, music theater, technical theater, visual arts, vocal music and writing.

In addition to the school, the home of Levi and Catherine Coffin was located on school grounds. They were well-known abolitionists, helping slaves escape from the south into the free state of Ohio and on to Canada. Levi Coffin is often called the “President of the Underground Railroad.”

The double-side marker in front of the high school not only explains this history, but also includes a bronze medallion in Joseph Ray’s imagine in honor of his life-long dedication to educating young people. Not bad for a Valley Grove boy. Not bad at all.