In this series, we’ll talk to Ohio Valley residents who struggle with autoimmune problems and share their stories. Series author Laura Jackson Roberts opens up about living with Sjögren’s Syndrome in this inaugural feature.

What is Sjögren’s Syndrome?

What is Sjögren’s Syndrome?

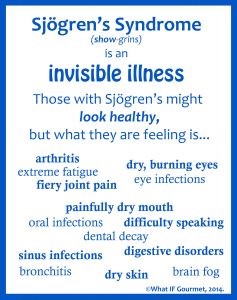

According to the Sjögren’s Syndrome Foundation, “Sjögren’s (‘SHOW-grins’) is a systemic autoimmune disease that affects the entire body. Along with symptoms of extensive dryness, other serious complications include profound fatigue, chronic pain, major organ involvement, neuropathies and lymphomas. Although many patients experience dry eyes, dry mouth, fatigue and joint pain, Sjögren’s also can cause dysfunction of organs such as the kidneys, gastrointestinal system, blood vessels, lungs, liver, pancreas and the central nervous system. Patients also have a higher risk of developing lymphoma. Today, as many as four million Americans are living with this disease.”

How Did It Begin?

In my early 30s, I began to feel sick. A vague, flu-like feeling came and went. My bones ached. I struggled with insomnia and had to rest during the afternoon to survive the day. I was tired, always, to the point of exhaustion.

When I was 35, I went back to school to get a master’s in creative writing. True to the American spirit, I couldn’t simply get through academia — I had to beat it into submission. I worked harder and longer than I’ve ever done, for anything. The stress was constant, and in addition to the increasing body aches, sometimes my brain didn’t work. Like having oatmeal in my head, my thoughts couldn’t penetrate a thick layer of sludge. I felt dull and stupid. Words wouldn’t come, authors and book titles slipped my mind, and I couldn’t remember acquaintances’ names. (This was “brain fog,” a most frustrating symptom of autoimmune disease.)

The eye problems began soon after. I’d wake up in the night feeling like my eyes were full of silica. My lids would be glued to my eyeballs — it was agony. The disease was attacking my tear ducts, and then it moved on to my salivary glands and dried up my mouth. My gums receded and exposed raw nerves.

There were other symptoms: digestive troubles, headaches and the mildest cold made me incredibly sick. It took me years to realize that they were all connected.

Getting Diagnosed

Getting Diagnosed

It takes the average patient three years to be diagnosed with an autoimmune disease. I was no exception. I saw a host of doctors, but specialists don’t talk to other specialists, so nobody ever looked at all my symptoms together. In fact, it wasn’t until my mother was diagnosed with Sjögren’s that I began to wonder if I suffered from the same condition. I asked for a Sjögren’s test, and confirmation was a relief, in a way.

There’s no cure for Sjögren’s or any autoimmune disease. Treatment revolves around a) managing symptoms and b) preventing flare-ups. I use drops and ointment so thick that I walked into a ficus one night. I have punctal plugs in my tear ducts to keep the moisture from draining away. I took Lyrica for pain, but after 10 days on the drug I began to hear phantom crickets in my head and stopped. The chirping continued for nine months. In my cabinet you’ll find antacids and antidepressants. I’m open to new prescriptions but unwilling to take anything that makes me feel worse or hear insect songs.

How Sjögren’s Affects My Life

Most of the time, my eyes hurt and I’m tired. We’re all tired, right? It’s the American mantra. We pride ourselves on our fatigue because it illustrates how hard we work, and if there’s one thing Americans love, it’s hard work to the point of exhaustion. I don’t know why, but I’m guilty of it, too. I love opening my planner and seeing the entire week covered in ink, scribbles in every corner. Sometimes I’ll make checklists of things I’ve already done just so I can have the satisfaction of checking them off. Write Weelunk story? Check! Clean up dog vomit? Check! Get the mail? Check — I got the hell out of that mail, today.

Accomplishments make me feel valuable. But autoimmune disease robs me of that feeling because I’m too tired to even read my checklist. On any given day, I have a finite amount of energy. I can do a certain number of tasks, be they for work or play, and then I have to rest. If I pull the weeds in front of my house, I’ll be done for the day. Pain and exhaustion will set in. If I spend an afternoon preparing a holiday meal, I’ll collapse before I serve it.

Guilt and Frustration

I get a lot of advice from people who mean well but don’t understand: Take probiotics. Avoid dairy. Meditate. Exercise more. I try it all, but the advice keeps coming. Someone once said, “At least you don’t have cancer.” That one was particularly awful because I tell myself the same thing whenever I feel like crap: Hey idiot, you don’t have cancer. You’re just tired.

But I’m not “just tired,” and I’m not lazy. Autoimmune disease forces me to accept that my body, the vessel I’ve been given to carry me through this life, has turned against me. I cannot rely on it when I desperately need it. Deep inside, I feel betrayed by my corporeal form.

With any chronic disease, the diagnosis is two-fold: we need to come to terms with the fact that our bodies are limited, and we also need to learn what we can still do. Acceptance doesn’t mean that I give up on treatment. This is perhaps where the real strength is required because it’s tiring and sometimes frustrating to search for help. As of July 2018, I have relationships with an osteopath, a rheumatologist, a neurologist, a gastroenterologist, an ophthalmologist, a naturopath, a massage therapist, a chiropractor, a physical therapist, a reiki master, a psychologist and a yoga teacher. Every one of these kind practitioners has helped me in some way, but it’s up to me to put the puzzle pieces together. While the massage may help me today, avoiding gluten may help more tomorrow. The onus is on me to look at every method of treatment, evaluate if and how it helps, and find a way to use it to my benefit. Similarly, it’s up to me to acknowledge when a course of treatment no longer serves me and to walk away.

What I Wish People Knew

With autoimmune disease, you have to think of your doctors and therapists as a support team. And you have to be the leader because they don’t talk to one another. It’s also important to trust your gut. Sometimes, professionals miss the mark. Sometimes they blow you off. If you find a good one who listens, stick with them.

Autoimmune disease feels shameful because the problems are on the inside. I look fine. My loved ones know I’m doing my best, but I do wish folks knew the reason my landscaping is full of weeds and my Christmas wreath is still on the stairs isn’t because I’m a slob. It’s because I’ve given the day’s energy to my children and to writing this piece for Weelunk. It’s because I woke up with a finite amount of it, and when it’s gone, it’s gone. And I hope that tomorrow I can pull those weeds. But if I don’t, it’s not the end of the world.

Clinicians believe that autoimmune disease may begin during times of trauma or extreme stress, and autoimmune diagnoses are skyrocketing. Having little children was stressful for me, and graduate school probably pushed me over the edge.

The best time to work on managing stress is now. Not tomorrow, not on vacation next month. We get one body, as they say, and though our culture tells us that taking time for ourselves is lazy or unproductive or downright un-American, our culture is wrong. It’s tough to watch my husband do all the work, but sometimes, I just have to give in.

Final Thoughts

Sjögren’s has given me a different perspective on life. Because I have a finite amount of energy each day, I’ve learned to prioritize the things I love over chores. And while I can’t ignore those weeds out front forever, I also know that each moment spent writing or walking in the woods is one I’ve chosen for me, to put in my memory bank. When you make that choice for each day, you realize how responsible you are for your own happiness. I’m allowed to feel sad and tired — and I do, sometimes — and I’m allowed to give myself the gift of fun and joy.

Chronic conditions have a way of whittling life down to bare bones. Some days I have to pull the weeds, of course. But each day, I get to make that choice. Sjögren’s Syndrome always reminds me to choose wisely.

If you have an autoimmune story and would like to share, please email Phyllis Sigal at Phyllis.Sigal@weelunk.com.

• Laura Jackson Roberts is a freelance writer in Wheeling, W.Va. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Chatham University and writes about nature and the environment. Her work has recently appeared in Brain, Child Magazine, Vandaleer, Animal, Matador Network, Defenestration, The Higgs Weldon and the Erma Bombeck humor site. Laura is the Northern Panhandle representative for West Virginia Writers, a blog editor for Literary Mama Magazine and a member of Ohio Valley Writers. She recently finished her first book of humor. Laura lives in Wheeling with her husband and their sons. Visit her online at www.laurajacksonroberts.com.