Wheeling natives have made their mark all over the nation and the world. They are actors, like Joyce DeWitt and John Corbett; labor activists, like Walter Reuther; musicians, like Leon “Chu” Berry and Mollie O’Brien; political leaders, like Walter Fisher; and authors, like Leo Brady. We can add sports legends, astronomers, college presidents, and other notable professions to that list as well. While it is always inspiring to see someone from Wheeling take center stage, I am often just as fascinated by finding hints of Wheeling on small scales in unexpected places.

My Honors students and I from California University of Pennsylvania collaborate with the Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh every semester to tell the histories of northern Appalachian communities, including Wheeling and Moundsville, along with places in southwestern Pennsylvania. Last spring, we spent time researching historical sites in Washington, PA, and I never expected to find the ghosts of old Wheeling hiding there.

While there are many historical sites throughout Washington County, PA, over half the students in my class were clamoring to conduct research at the LeMoyne Crematory, the first crematory in the Western Hemisphere. Dr. Francis Julius LeMoyne believed that cremation was more sanitary than burials, arguing that diseases of the deceased made their way into the water supply and infected the living. LeMoyne and his assistants conducted the first cremation in December 1876 at the crematory he had built on Gallows Hill, a short drive from his home and office in downtown Washington. By the time the Crematory closed in 1901, 42 bodies had been cremated there, including LeMoyne himself in 1879.

My students and I visited the crematory, a small, 20’ x 30’ brick building, on a chilly afternoon in February. Clay Kilgore, director of the Washington County Historical Society, which cares for the Crematory, told us about the history of the building, showing us the oven and explaining how cremations would have been performed. As he talked, however, my eyes kept wandering to the walls of what would have been the room where services were held. The white walls were filled with cursive writing, and I was anxious to read it all.

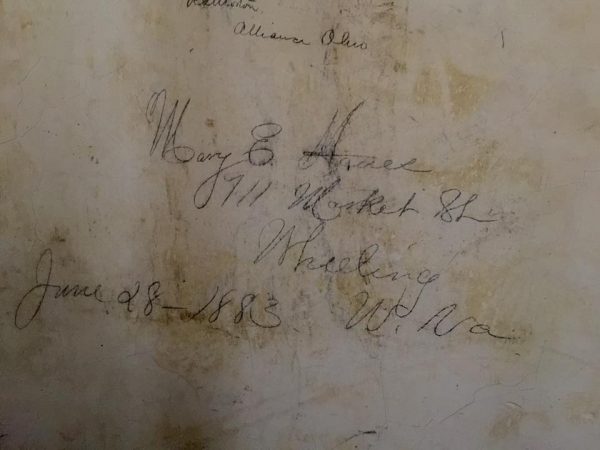

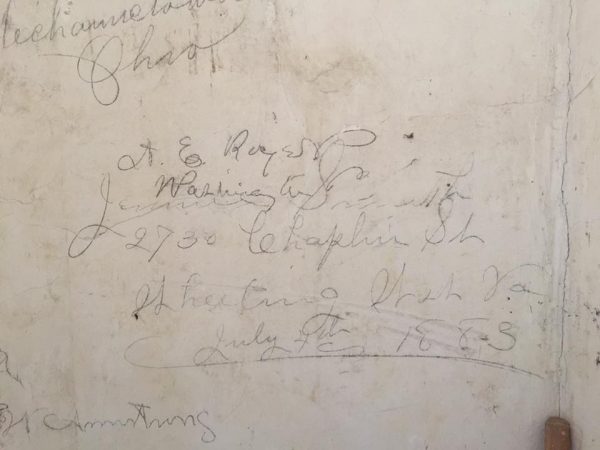

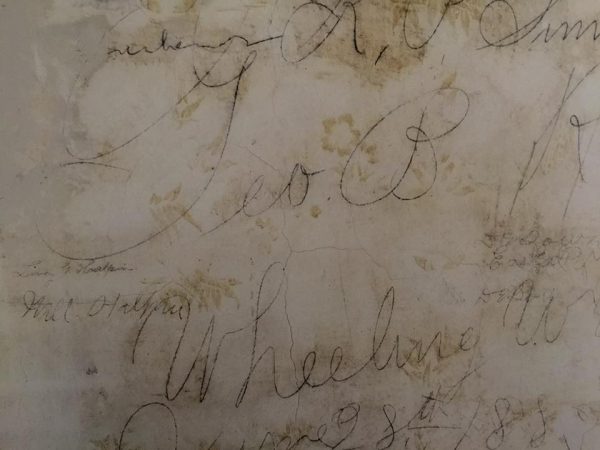

Imagine my surprise when I realized that these scrawls were graffiti from the turn of the 20th Century. I looked closer and discovered that at least half of the signatures were from Wheeling, West Virginia! My excitement grew as I discovered that many of the signatures also contained street addresses. Who were these people from Wheeling? Why did they write on the walls of a crematorium? What were they doing in Washington, PA, which would have been quite a haul prior to automobiles? Did they sneak in and write their names? Was it on a dare?

I set out to find the answer to these questions and was not disappointed.

The names are written in pencil on nearly every surface of the crematory, including the oven. In most instances, the first and last names are signed, as well as the city and state of the writer. Sometimes the bold artists even signed their house numbers and street addresses. The names were written between 1881 and 1924, which means that young people were writing on the walls for at least twenty years of the crematories operation. Although the exact reason why these men and women scratched their names here is not known, it has been speculated that they were likely male students and their friends from nearby Trinity Hall Military Academy. (Now the site of Trinity High School.) We know that young people from Wheeling attended this elite school in lieu of Linsly Military Academy with the likes of Andrew Carnegie, Jr. Trinity Academy was once considered the best outfitted military school in the country and was often visited by President Ulysses S. Grant, who was a known staple in Washington County life during his time in office.

As to their motivation, most people think that the students signed their names on the walls as a dare. Given that cremation remained uncommon and even stigmatized during the time in which the crematory operated, it is easy to believe that breaking in and signing your name on the wall would have been a teenaged way of demonstrating bravery. At some point, wallpaper was hung on the walls in an attempt to stop the graffiti artists from their nightly work. During restoration of the crematory in the early 1990s, the wallpaper was removed and the names revealed. The historical society considers the names part of the crematory’s history and left the walls uncovered. Volunteers carefully inscribed them and a plaque now hangs in the reception room of the crematory detailing names, dates, and other information, including city and state of many of the writers.

After returning home with nearly 100 photos of the crematory, I set about to research some of the Wheeling names written on the walls. While some of the names were complete, others, like W. Ripley, gave me little to go on. Other names read like they were in an address book: “Erin J. Phillips, 637 Main St., Wheeling, W. Va, June 28, 1883.” I realized that the only ones who signed their full addresses were young women, likely from nearby Washington Female Seminary (1836-1948), which was co-founded by none other than Francis Julius LeMoyne. And Wheeling’s own Rebecca Harding Davis, author of Life in the Iron Mills, is its most famous graduate.

Given that women most likely change their names after graduating and getting married, locating them and their descendants seems hopeless, though I know that the directories at the Ohio County Public Library’s Wheeling Room might yield some insight for a more ambition researcher. I did find Mary E. Hanes in the 1920 Census. She still lived on Market Street, maybe even at the same house number that she had written on the wall in 1883. I wonder if, at 62, she remembered her daredevil night in the crematory that June. I also found a Miss Jennie Smith who drew an audience of more than 3,000 in Wheeling in 1886, according to a Wheeling newspaper. Whether it was the Jennie Smith who lived at 2730 Chapline Street when she signed the crematory wall on Independence Day 1883 is unknown, but I’d like to believe it was her.

I did, however, find some success with “Geo B. Riddle.” First, I found his family’s census records from the 1880 US Census. From that I learned that George B. Riddle was the son of James H. and Kate Riddle. James’ job was listed as “Supt Water Wk,” which means that he was the Superintendent of Water Works, which would have been a well-paying job in that era. Kate Riddle’s occupation is listed as “keeps house.” Together they had nine children. Their two oldest sons, James and Charles, are listed as “Nail Feeders,” which most likely indicates that they worked at LaBelle Nail Plant.

George B. Riddle was just 13 years old when this census was taken. West Virginia Vital Records and Statistics shows his date of birth as April 6, 1867 in Wheeling. And then, I lose track of George B. Riddle from the wall of the LeMoyne Crematory in Washington, PA. The George B. Riddle born in Wheeling, son of James H. and Kate. He is not listed under Marriage or Death in Vital Records and Statistics, though he might turn up in old yearbooks or school records at the Trinity Hall Museum in Trinity High School in Washington, PA, if, in fact, he was a student there.

In my research I did uncover interesting facts, including that his father James died in Wheeling at age 84 in 1919. Cause of death: “Lorine poison in mistake ‘accident.’” I can’t find any information about “Lorine,” but upon closer inspection of the handwritten death certificate, it appears that maybe he died of iodine poisoning. Iodine can be toxic in large quantities. I wonder, though, if the undertaker or the person filing the report meant the quotes around “accident” to be ironic, as we would today, or if he meant the word to be emphasized. I realize, of course, that it was mostly likely for emphasis and not to indicate suspicious circumstances.

Searches for John Trew and Arthur Charles Buster yielded nothing concrete. I got the same results while searching for Jason Huntington Rives and Merl Harris, who signed the wall on January 25, 1883. It made me wonder if they might have used pseudonyms to protect themselves, but it seems unlikely. Why go through the trouble of breaking into a crematory and have no proof that you did it?

I come away from this research of the names on the wall with mixed feelings. Part of me hoped that these young people, earning their educations nearly 50 miles away from home, would have gone on to do great things. I was dreaming of writing stellar biographies for each one. Instead, I found something better: middle class Wheeling kids leaving their mark on history in the pallid moonlight that no doubt crept in the cracked door they entered into the LeMoyne Crematory. Can’t you see them there with their friends, pencils raised, nervously giggling, recording their names for posterity likely on a dare? They were testing their youth in the face of death and its aftermath and hoping to leave behind some kind of proof that they were alive. Long before Killroy, Jennie and John and George was here.

For more information about these names and the LeMoyne Crematory itself, please watch my students’ digital story below. The LeMoyne Crematory is available for tours by contacting the Washington County Historical Society 724-225-6740.

Link to my students’ video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DIY3WFc6sQ4