If your skin crawls just reading this, you’re not alone. (I checked my hair seven times as I wrote that paragraph.) Ticks have earned their place on the horror scale, and they’re dangerous. Fortunately for me, the tick hadn’t embedded itself yet.

Regarding ticks and Lyme Disease, it’s hard to know what’s true and what’s myth. How worried should we be about Lyme, and what can we do to prevent infection?

THE HISTORY OF LYME DISEASE

THE HISTORY OF LYME DISEASE

When Lyme Disease first appeared in Lyme, Connecticut, in 1975, doctors misdiagnosed it as childhood rheumatoid arthritis. (Children were the ones most commonly diagnosed as they were often outside.) A few years later, clinicians linked the symptoms to bacteria carried by the deer tick. Between 1997 and 2003, you could get vaccinated for Lyme, but the manufacturer withdrew the vaccine from the market, as the disease, at that time, was limited to New England.

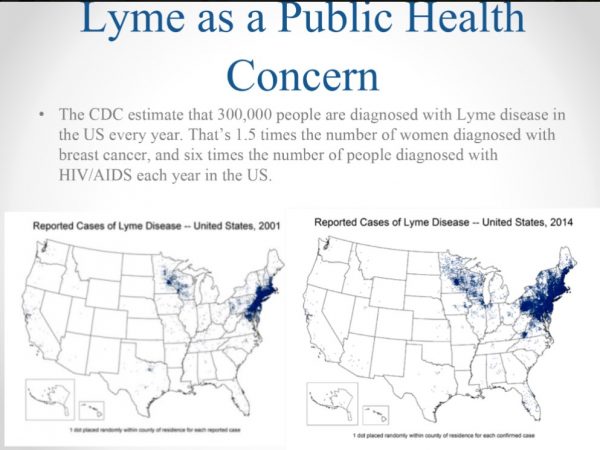

But now, Lyme Disease is here in the Ohio Valley. To get an idea of what’s going on, I called Howard Gamble, administrator at the Wheeling-Ohio County Health Department. He explained that the disease is moving down the eastern corridor from the northeast. It’s now considered endemic in Pennsylvania and West Virginia and is spreading west across Ohio. Additionally, Lyme is moving down from the Great Lakes region. The two areas of prevalence will eventually merge.

Three species of tick are found here: the dog tick, the lone star tick and the deer tick. The latter is the one that carries Lyme Disease. However, Lyme is not the only tick-borne pathogen; they also carry Rocky Mountain spotted fever, ehrlichiosis and babesiosis, among many others.

Humans are helping the spread of Lyme Disease because land management practices have changed. More people are moving out into suburban and rural areas, where ticks are more prevalent. Also, as we allow farmland to be re-taken by forest, we create tick habitat. This habitat is frequented by deer and small rodents, and these animals are bringing the ticks with them as they move about the area. Deer are common even in urban areas now and facilitate the transmittal of the parasites.*

In addition, as the climate warms, so do our winters. Ticks survive these new, milder temperatures, and disease specialists warn that we’ll see regular tick population explosions this summer and in the future.

In addition, as the climate warms, so do our winters. Ticks survive these new, milder temperatures, and disease specialists warn that we’ll see regular tick population explosions this summer and in the future.

For now, it’s impossible to stop the spread of Lyme. With a disease like rabies, we can drop bait from above to vaccinate wild animals. But ticks are too small to bait. That means the best defense we have against them is vigilance.

BY THE NUMBERS

It’s difficult to know exactly how many people in any given area have contracted Lyme Disease. According to Howard Gamble, that’s because a) Lyme can mimic many other diseases, and b) when a patient comes to a medical facility complaining of Lyme-like symptoms after time spent outdoors, a physician will often begin treatment without waiting for the results of a Lyme test.

“It’s growing from the eastern panhandle and becoming more prevalent as it moves westward,” Gamble said. “So, our eastern panhandle, we would consider it pretty prevalent out there. In the eastern counties, it’s more than 100 per county. A lot of times, we don’t test when you come in. Nowadays, you just start the treatment. In Ohio, from 2008 to 2017, the number of cases dramatically increased in the in the eastern counties like Belmont, Jefferson, and Harrison. We probably have more cases of Lyme than what’s being reported.”

Lyme infections also are difficult to count because the disease so closely mimics others like multiple sclerosis, cardiac and pulmonary issues, ALS and autoimmune disease. Lyme can affect any organ of the body.

LIVING WITH LYME

Susan Hagan lives here in the Ohio Valley, but she was living in Greenwich, Connecticut, when she started to feel ill.

Susan Hagan lives here in the Ohio Valley, but she was living in Greenwich, Connecticut, when she started to feel ill.

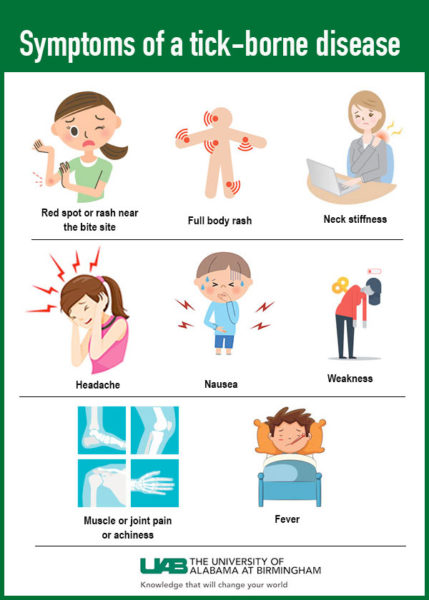

“I had been sick for a long time,” she said. “Off and on, because some days you’ll feel fine. It was flu-like symptoms, but it was also things like foggy brain, sore joints, some other odd things like allergic reactions. It’s so different for everybody.”

Though the town of Lyme wasn’t far away, her doctors never considered Lyme Disease because she didn’t have the infamous bullseye rash.

“Ten years ago, everybody figured the bullseye rash was a done deal,” she said. “Bullseye rash, you have Lyme. No bullseye rash, you don’t have Lyme. And they said chronic fatigue, they said rheumatoid arthritis, MS, Lupus. They said all those kind of things, but then the tests … wouldn’t come back positive.”

She also experienced nausea, headaches, stomachaches, anxiety and depression, and sensitivity to light and sound. Doctors kept leaning toward chronic fatigue syndrome and arthritis because Lyme Disease still wasn’t on their radar.

When tests finally confirmed Lyme, she began a two-year course of treatment, even getting a PICC line to deliver IV antibiotics.

Hagan continues to experience the effects of her infection and says there’s some disagreement in the medical community about whether or not Lyme Disease can be totally eliminated from the body. She’s had what she described as flare-ups for many years after the treatments ended.

Hagan advocates for herself—she says it’s imperative when it comes to Lyme Disease. To this day, she has a difficult time getting clinicians to investigate her Lyme suspicions. She’s since educated herself on the disease. It’s an ongoing task because what we know about Lyme keeps changing, and the medical community can’t keep up.

PREVENTION

The most important part of prevention is wearing the right clothing, i.e., long pants and sleeves, closed-toe shoes, and socks. Gamble suggested using insect repellant with DEET both on your exposed skin and on your clothing. Once you return home, do a thorough tick check, and ask someone to check your hair.

It’s also helpful to check your dog after a hike. Use flea and tick prevention, and ask for Lyme testing at the vet. My dog tested positive for Lyme in 2017 at her annual checkup and spent a month on antibiotics. Fortunately, the vet caught it early and she made a full recovery. Susan Hagan, who used to run a dog kennel, recommends Seresto collars for flea and tick prevention, as well as using a lint roller on both dogs and ourselves to pick up the insects.

After a tick bite, it’s vital to remove it and get treatment as soon as possible.

“A tick must be attached or embedded for at least 24 to 48 hours before the Lyme or the bacteria can be transmitted,” Gamble said. That’s why physicians start treatment without waiting for the results of a lab test.

GET IT OFF ME

According to Gamble, the proper way to remove a tick is to get tweezers close to the base of where it has embedded in the skin and pull out. You’re going to pull some hair and skin, but you’re going to get the whole tick out. (If the mouthparts detach and remain, don’t panic: Lyme cannot be transmitted this way.)

“If you see it [crawling] on you, knock it off, scrape it off, pick it off with tweezers, and just crush it,” Gamble said. “If you see it embedded, then you have to be a little more careful. Now, we don’t recommend—no one recommends—the folklore methods of removal, [like] burning a match and then placing it on the back of the tick. No. Usually, you burn yourself. Don’t cover it or smother it with nail polish.” Recent social media posts suggest smothering a tick with essential oils or Dawn soap. This is bad advice, as per a 2006 article in an infectious disease journal:

Experimental evidence suggests that chemical irritants are ineffective at persuading ticks to detach, and risk triggering injection of salivary fluids and possible transmission of disease-causing microbes. In addition, suffocating ticks by smothering them with petroleum jelly is an ineffective method of killing them because they have such a low respiratory rate (only requiring 3-15 breaths per hour) that by the time they die, there may have been sufficient time for pathogens to be transmitted.

People will often bring ticks into the Health Department for testing, but this isn’t necessary, as testing isn’t done on ticks that bite humans. A tick may test negative for Lyme, but you may have been bitten by another, unseen insect and infected by that one. Testing individual ticks isn’t a reliable way to know if you’re infected.

Nor can we rely on a rash as an indicator.

“It’s not always going to be the telltale bullseye that we see in textbooks,” Gamble said. “These rashes can be in the way of a blotch or a line. It can be a large rash. And then that’s when you have to think, ‘Okay, what was I doing? Yes, I was outside—maybe I need to go and check this rash and tell the physician I was outside.’”

WHAT TO REMEMBER

Unfortunately, Lyme Disease is here, so we have to take precautions. Remember, prevent tick bites by wearing protective clothing and insect repellent; check for ticks when you come inside; and see a doctor as soon as possible if you find one embedded in your skin. Never take chances.

*Animal Fact: The Virginia Opossum can eat 5,000 ticks per season. Opossums are also usually immune to rabies, so it’s a good idea to let them do their job in your yard.

Further reading:

Fact Checking: Liquid Soap to Remove Ticks

WV DHHR Office of Epidemiology

• Laura Jackson Roberts is a freelance writer in Wheeling, W.Va. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Chatham University and writes about nature and the environment. Her work has recently appeared in Brain, Child Magazine, Vandaleer, Animal, Matador Network, Defenestration, The Higgs Weldon and the Erma Bombeck humor site. Laura is the Northern Panhandle representative for West Virginia Writers, a blog editor for Literary Mama Magazine and a member of Ohio Valley Writers. She recently finished her first book of humor. Laura lives in Wheeling with her husband and their sons. Visit her online at www.laurajacksonroberts.com.