On Sept. 1, 1907, two German immigrants, Valentine and Anna Reuther, welcomed their second child to the world. A healthy baby boy, Walter Reuther was one of 41,641 souls who would be counted in the 1910 Wheeling Census three years later. The sheer size of the city reflected the changes it had witnessed since the end of the Civil War just over 50 years earlier.

The Industrial Revolution had Wheeling firmly in its grip, with heavy manufacturers popping up in every part of town, drawing thousands of migrants like the Reuthers looking for better wages or to simply escape the monotony of rural life. It was in this city, and amidst this industrial environment, that Walter would grow up and form many of the values and beliefs that propelled his rise in the labor movement, where he would eventually lead the powerful United Auto Workers union for 24 years until his death in 1970.

Though much has been written of Walter Reuther and his contributions to organized labor, the importance of his childhood in Wheeling in his formation is less emphasized. Though he went on to rub shoulders with Kennedys, and his face graced the cover of Time magazine not only once but twice, his life began with much humbler beginnings. Before he would lead the United Autoworkers in strikes and bring General Motors to its knees, he was scraping his own on the streets we drive and walk today.

The Reuthers — like much of Wheeling’s proletariat class — lived and worked in the old Eighth Ward, today’s South Wheeling. Dense and dirty, the neighborhood crammed over 6,700 people amidst factories and rail lines into the narrow floodplain between the Ohio River and the steep hillside, a density comparable with the modern-day borough of Queens in New York City. According to Callin’s City Directory of that year, in 1907, the Reuthers were living in a modest brick row house at 40 35th Street. Like many working-class families across the city, the Reuthers lived within close distance of Valentine’s place of work: the Schmulbach Brewing Company stables at the corner of 33rd and Wetzel streets, the building now inhabited by Kennedy Hardware.

Though South Wheeling earned a reputation for being a tough part of town full of factories, flames and foreign tongues, life for the working class across all of the city’s eight wards was difficult. According to the 1910 Census, the 7,809 wage earners employed in Wheeling’s manufacturing sector made an average of only $567 annually, just over $14,000 in today’s dollars. Despite their low earnings, these workers (predominantly men) worked 12-hour shifts six days a week, with Sunday work altering weekly. The work, especially in the iron and steel mills and glass factories, could be incredibly dangerous, with injuries or fatalities occurring regularly. Indeed, Walter himself would lose his right big toe in an accident while working at the Wheeling Corrugating Company’s tool and die shop at the age of 17.

It was in this harsh working environment that Valentine Reuther had become involved in Wheeling’s labor movement, initially as a young member of the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel and Tin Workers while working at the Riverside Iron Works, where he worked after first arriving in Wheeling. His admission into Amalgamated, however, was made possible only by his status as a skilled heater and his ability to speak English. In the mill floor hierarchy, skilled tradesmen in the union were the so-called aristocracy of labor, while the common laborers were seen by management and Amalgamated members alike as an expendable commodity. These laborers, more often than not recent immigrants, often worked the most dangerous jobs for the lowest wages. Valentine was disturbed by the discrimination his co-workers experienced from what he saw as their own kind. His youngest son Victor would later write of his father’s views, “It was bad enough, he insisted, that the employers exploited the so-called Hunkies, Micks, Wops, Polacks and others, why should workers scorn one another merely because of differences in birthplace and way of life?”

It was this experience working in the iron and steel mills that guided Valentine as he worked to organize his fellow brewery workers into a union while working at the Schmulbach brewery and living on 35th Street. Most importantly he ensured that membership in the union — a local of the International Brewery Workers Federation — was open to any and all workers in the Schmulbach brewery, not just the skilled craftsman. This led the men of the brewery to elect him as their representative to the Ohio Valley Trades and Labor Assembly, at that time representing approximately 4,000 workers spread out among 42 trade and craft unions.

Even though Valentine was working his way through the ranks of organized labor and earning a steady paycheck at the brewery, life was not always easy in South Wheeling. Living in what was perhaps the least-developed neighborhood in the city, the Reuther boys spent their earliest days in a house with no electricity, no running water and no indoor toilet. But despite their hardships, the Reuthers were members of a large and acceptable contingent of Wheeling’s culture and society, a privilege many of their fellow immigrant neighbors did not enjoy.

According to the 1910 Census, nearly a quarter of Wheeling’s population was either German immigrants or their children. The city boasted a German bank, a German insurance company, German churches in both the Catholic and Protestant faiths and numerous newspapers, clubs and cultural organizations. The Reuthers attended The First Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church on Market Street in Centre Wheeling (today’s Towngate Theatre), and Valentine was active in the Beethoven Gesangverin singing society. It was his German birth that — even as an immigrant — spared Valentine from the discrimination he witnessed Irish, Italians and Eastern Europeans endure in the mills.

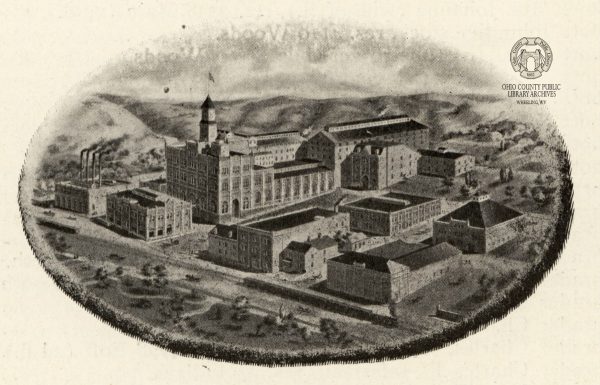

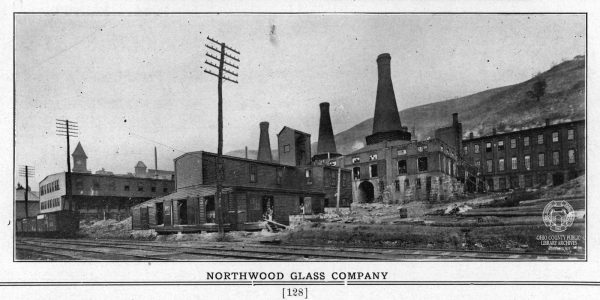

Within a few years of Walter’s birth, Valentine and Anna decided that their 35th Street home was too small for their growing family of three boys, with two more children to come. The Reuthers built a new house at the corner of 37th and Wetzel streets, still only a few blocks from the brewery but more spacious and with modern amenities. It would be in this house that Walter, along with his brothers Ted, Roy and Victor, would grow up. Their new house was directly adjacent to the Northwood Glass Company’s factory, which at that time took up nearly both sides of the 3600 block of Wetzel Street. The family’s new corner of the neighborhood provided ample opportunity for the rambunctious Reuther boys to play and get into mischief. Their house sat right next to an abandoned mine perfect for exploring, while the Ohio River flowed just blocks away.

But not all locations that beckoned the boys were natural or abandoned; the Northwood Glass Company was a popular spot for the neighborhood’s children to congregate, despite the inherent danger glassworks posed for young children. One day in 1916 at the age of 9, Walter followed his older brother Ted into the glassworks where Ted worked at the tender of age of 11, long before the advent of child labor laws. As Walter roamed the factory floor, either he or a glassworker was not paying attention, and the young boy was struck in the face with the hot end of a blowpipe dipped in molten glass. Walter nearly lost his eye and carried a scar on the side of his nose for the rest of his life. However, accidents like these were almost common in industrial South Wheeling, and he was fortunate not to have joined the rolls of accidental deaths that darkened working-class life.

Had the West Virginia voters not approved the state’s prohibition measure at the ballot box in 1912, Ted may never had gone to work at Northwood Glass and young Walter may not have been standing in the blowpipe’s path. Just a few years after building their Wetzel Street home, economic calamity struck the Reuther household as statewide prohibition took effect in 1914, shutting down the Schmulbach brewery and taking Valentine’s job with it. Valentine had campaigned heavily across the state against prohibition but could not stem the tide of teetotalers. The final election results were 164,945 in favor with only 72,603 against, though without the help of Ohio County, which was one of only three counties to vote against prohibition. Valentine struggled to regain steady work, and the family’s finances were greatly strained in the mid-1910s. Ted’s job at Northwood glass, though paying only 8 cents an hour, was a needed and much welcome contribution to the family’s coffers.

Things began to look up for Valentine and the Reuther family after he took a job with the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, selling “industrial insurance” to his neighbors and former co-workers in South Wheeling. Still well-regarded for his leadership in the brewer’s union and the Ohio Valley Trades and Labor Assembly, Valentine was able to capitalize on his reputation and friendships in his new endeavor and enjoyed modest success in the insurance business. The family’s newfound fortune allowed the four Reuther boys to attend school, a privilege not afforded to all of Wheeling’s working-class youth. Of Wheeling’s 13,682 school-aged children, only 9,290 were listed as attending school in the 1910 Census. At least 265 were working in the manufacturing sector like Ted had, while many worked as extra hands in small shops or in family businesses. Even during the hard times at the onset of prohibition, the Reuthers instilled in their children a deep appreciation for learning, with Valentine holding debates with the boys on topics such as politics, economics and religion.

Despite this, at the age of 15, Walter dropped out of his sophomore year in high school to work as an apprentice in the tool and die shop at the Wheeling Corrugating Company plant along Wheeling Creek. While in school, Walter had taken to the industrial arts program more than the academic subjects and was eager to learn a skilled trade, the memory of the hard times after prohibition still ingrained in his memory. He excelled in the tool and die shop, though an accident cost him one of his toes. Still a stubborn teenager, Walter reportedly took his severed toe with him to the hospital and demanded the surgeon sew it back on because he would need the aid of both toes to keep playing center in his favorite sport of basketball. Though he ultimately lost the toe, he learned how to balance himself on nine toes and continued to play basketball as center.

By the time Walter left Wheeling in search of better opportunities in the automobile industry in Detroit, his world — his Wheeling — had changed; his father had by then sold insurance longer than any other previous job, and the family had moved from South Wheeling to a quiet farm along Fairmont Pike (today’s W.Va. 88) on Bethlehem Hill.

As the Reuther boys grew, so too did the city they called home. Wheeling had grown literally, as the city annexed many of the National Road streetcar suburbs and swallowed up the more working-class areas of Warwood and Fulton. The city of under 42,000 that Walter had been born into swelled by 1930, three years after his departure to Detroit, to a peak of 61,659. The large immigrant communities began to assimilate, and kids with last names of Schafer, Proginsky and Flanagan lived on the same block, went to the same school, and said the pledge each morning with the same accent.

Though arguably no other Wheelingites would see the fame of Walter Reuther, the story of his family and their endeavor to provide their children with the American dream is one that is common throughout our city. Had it not been for Valentine and Anna’s hard work, sacrifice and emphasis on their children’s education, Walter Reuther likely would never have been on the cover of Time Magazine, and no kid from South Wheeling would have become known as the most dangerous man in Detroit.

Walter Reuther’s Wheeling was certainly a different Wheeling than we live in today, but the values that fueled his rise to fame are undoubtedly Wheeling’s values. Values such as hard work and an appreciation for education that still hold a central place in the Friendly City.

Reuther Source List:

- Brennan, Margaret. “A Brief History of South Wheeling.” Unpublished, April 23, 2007.

- Callin, W.L. Callin’s Wheeling City Directory. Vols. 27-89. Wheeling, W.Va.: W.L. Callin Co., 1904-1926.

- Dunham, Tom. Wheeling in the 20th Century. Bloomington, Ind.: First Books Press, 2003.

- Lichtenstein, Nelson. The Most Dangerous Man in Detroit: Walter Reuther and the Fate of American Labor. New York, N.Y.: Harper Collins, 1995.

- Reuther, Victor. The Brothers Reuther and the Story of the UAW: A Memoir. Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin, 1976.

- Sanborn-Perris Map Co. Insurance Maps of Wheeling, West Virginia [map]. 1890. Scale not given.

- U.S. Department of Commerce. Thirteenth Census of the United States Taken in the Year 1910: Supplement for West Virginia. Bureau of the Census. 1913.

• Nick Musgrave is a self-described history geek living in Wheeling, W.Va. He is a graduate of Hastings College in Hastings, Neb., where he earned his bachelor’s degrees in history and political science. When not writing for Weelunk or uncovering cool stories about the past, he can often be found reading in his hammock or trying to brew the perfect cup of coffee.