Nearly nineteen years ago Susan Haddad began renovations on the 1869 building that would become her iconic Centre Market restaurant, Later Alligator. In May 2020, Wheeling Heritage’s Betsy Sweeny purchased the 1892 McLain house in East Wheeling for $18,500 and began chronicling her renovation journey on Instagram. Though separated by generations, these two women share a common passion for and philosophy of restoration: recycle, repurpose, reuse.

“That’s all my hand…I just love design.”

Touring Later Alligator with Susan Haddad is like taking a crash course in historic renovation and collection. She zips from one item to another, recalling with absolute precision where and how she salvaged every brick, door, column, tile, and piece of Wheeling memorabilia. Her stories are punctuated by phrases like “I gutted this myself,” “I stripped everything,” and “I’ve climbed in many a dumpster,” weaving a common thread of sheer grit.

Let’s start with the doors. “99% of all the doors that are in here, I found.” The bar and bar wall are doors, stripped down of layer upon layer of paint and shellac. The oversized bathroom doors came from the old Fulton schoolhouse Haddad lived in for twenty-two years. She even took the plumbing access panels with her when she moved and used them to frame the doorway into the bathroom area. The two antique doors suspended beneath the My Club “Do Not Touch the Dancers” sign came from Haddad’s third grade classroom in Steubenville.

Then there are the floors. Haddad was determined to salvage the Wheeling Tile hexagonal flooring under the carpeting left behind by the former owners, but the thick layer of rubber paste attaching the carpet to the tile stumped many a local chemical company. “It was a nightmare to get up,” Haddad sighs. In the area where she was successful saving the original tile, Haddad filled in missing spots with shards of Wheeling bottle glass she found when the courtyard was excavated. Haddad still recalls chasing after the construction foreman mid-dig, shouting “‘No, no, no, stop!’—He wanted to shoot me!”

Where the original tile was unsalvageable, Haddad still sought a way to repurpose. One day in 2003 or 2004 she passed by the site where West Virginia Northern was renovating Wheeling Wholesale Grocery for its new Culinary Arts building. She spied “this beautiful wood” from the first floor in a dumpster and asked the foreman if she could have it. He turned her down, citing insurance policies that prohibited dumpster diving. “I’m sure he thought I was nuts,” she says. Fortunately, he gave her a call when they tore out the second floor and she got her original tongue and groove oak flooring after all.

The list goes on. Haddad rescued the building’s original Wheeling Corrugating tin ceiling from beneath multiple dropped ceilings. She repurposed slate chalkboards from the Fulton schoolhouse into a countertop for the back of the bar. Local artist Jeff Forster transformed an iron window guard from a now-boarded up window into an iron gate connecting Haddad’s building to one next door.

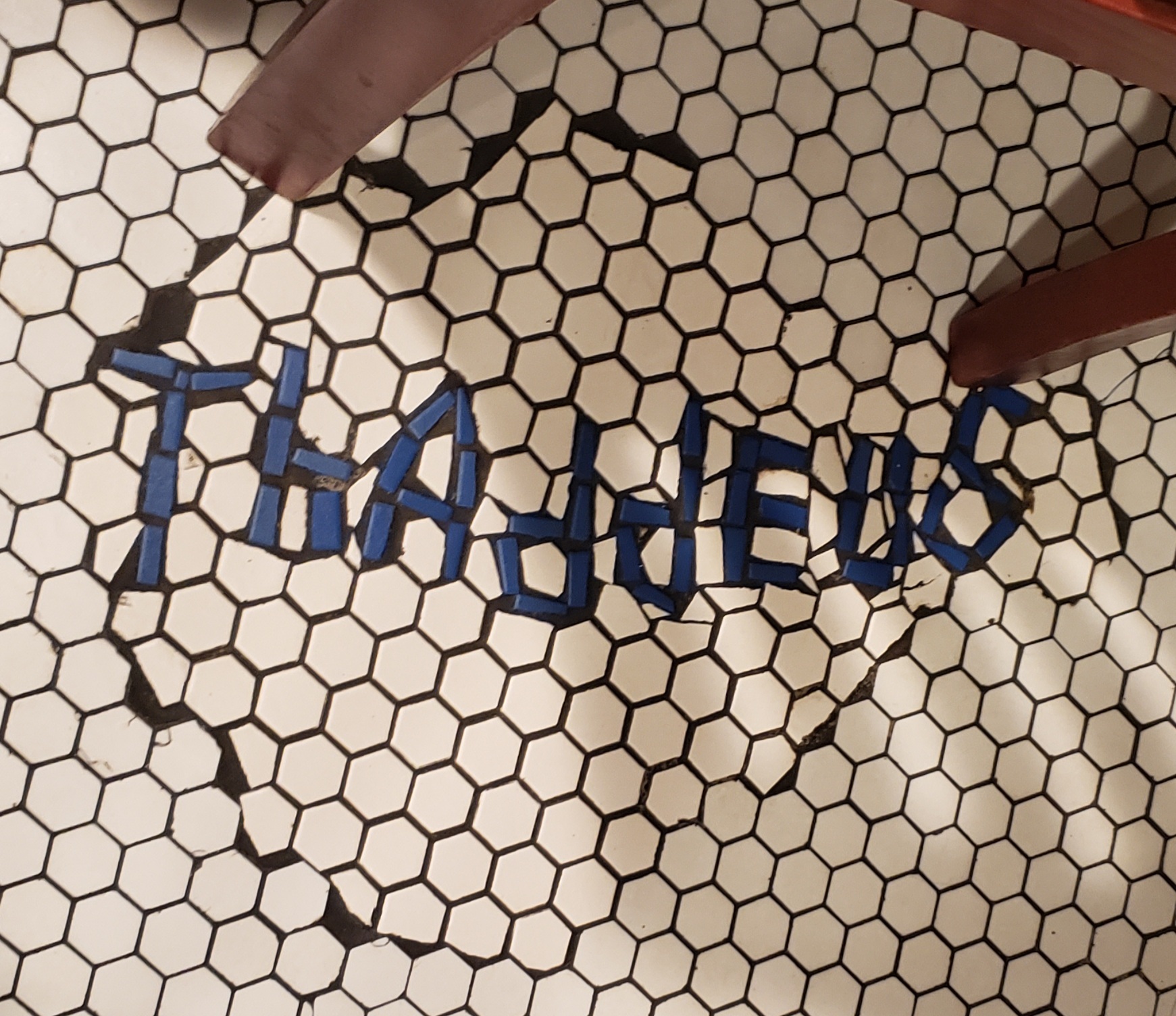

Haddad is the first to acknowledge that her one-woman mission to restore 2145 Market Street would not have been possible without the community of collectors that have helped her over the years. “There are a lot of scavengers in Wheeling!” she says. Her friend and co-developer, local collector Thaddeus Podratsky, earned a special place of honor in the rehabilitated tile floor, his first name spelled out in reclaimed glass. “Any historian in Wheeling knows who Thad is,” she says. Duly noted.

If there’s a single lesson to distill from Haddad’s renovation adventures, it’s to keep a sharp eye out whenever anybody discards anything in Wheeling. Haddad came across the S and T, and several letters besides, from the Main Street Stone and Thomas sign one morning before they were carted off to the landfill. The ornamental bricks framing the back patio walkway were salvaged from the old Straub Honda dealership downtown under cover of a “very, very dark” night. Even the slab that became the marble vanity in the women’s restroom was going into a garbage can when Haddad asked if she could have it. “Well that guy was smart and said, ‘for $60,’” she laughs.

When I ask her what advice she would give to someone planning to rehab an old building, Haddad sums things up nicely: “I had no idea what I planned to do and working alone for close to a year I very simply began to undo 150 plus years of the unknown. It probably was therapy. The longer I got into it the more I loved it. As for serious advice? Don’t wait until you are 60 years old as I did. Think positively. If there’s a plan, know at completion, it will likely be unrecognizable. And I think anyone would advise them to double what they planned on spending.”

“Pay attention to what you like versus what’s trendy”

Betsy Sweeny understands more than most the challenges of rehabilitating a “beautiful old mess.” As an architectural historian and Director of Heritage Programming at the Wheeling National Heritage Area, she helps historical building owners secure preservation funding and technical assistance. Now she’s restoring her own future home and taking her 64,000 Instagram followers along for the ride.

Like Haddad, Sweeny is dedicated to repurposing and sourcing as many local materials as possible. It helps that much of her 139-year-old house was locally sourced to begin with, built as it was at the height of Wheeling’s industrial era. She’s restoring the Wheeling Corrugating pressed metal ceiling in her kitchen and amassing quite the collection of LaBelle cut nails. Sweeny is a little surprised the tile surrounding her living room fireplace came from Cambridge, Ohio, not Wheeling, but she chalks it up to the sheer variety of options available in the region in the late 1800s.

Whatever she doesn’t find in her own home, Sweeny scouts out nearby and tries to keep consistent with the house’s historic character. She’s sourcing all her new lumber from Denoon Lumber in Ohio and glass from Dayton. She avoids plastics whenever possible and seeks out items readily identifiable as one material (“this is a metal, this is glass”). And just like Later Alligator, the McClain house is a community effort, sustained by the circulation of materials among friends. Her boyfriend supplied the brick for the back corner of her house from the Berry Building and her friend, Kellie Ahmad of Rust Belt Restoration, designed the stained glass transom for her front door.

Sweeny imparts three pieces of wisdom for anyone looking to embark on their own renovation project: First, don’t just rely on Instagram for the latest in vintage trends. She points out that you probably won’t be able to find the trendiest items in the local Goodwill store because someone will have already snapped them up. Spend some time figuring out the kinds of materials you respond to most – mixed metals, certain types of woods, etc.—and then keep your eye out.

Second, “things made of sturdy materials last a long time,” so there are certain items you can always find if you look hard enough: sinks, bricks, big rocks. Set an alert on Facebook Marketplace, she says, and they will come around to you eventually.

Finally, you don’t have to spend a lot of money on renovations, but you do have to be patient. The old contractor adage “you can have good, fast, or cheap: pick two” definitely applies here, she says. Poke around at Sibs, Goodwill, Construction Junction, and Restore in Pittsburgh and wait for the right materials to come along at the right price.

Sweeny is still mid-project, although she anticipates being able to move into her house sometime this Fall. Meanwhile, her social media profile continues to soar – she’s recently debuted a new website, betsysweeny.com, and is producing tutorials and behind-the-scenes videos on Patreon. Hers is a distinctly twentieth-first century approach to historic renovation, and yet it retains the values that drove Haddad in the early 2000s: keep it local and recruit your friends.