“Doctress”…“Lady Doctor”…“Girl Doctor”…These are just a few of the peculiar titles that have been given to some of the historic Wheeling women who worked as physicians. Today, most of us don’t think twice about women being doctors, but it hasn’t always been an acceptable career path.

In Wheeling, some of the earliest medical care has been provided by women. For example, the Visitation Nuns, and later the Sisters of St. Joseph, cared for patients at the first Wheeling Hospital in East Wheeling, starting in 1850.1 In addition, midwifery and nursing have often been seen as women’s fields. While there have been many female doctors and physicians keeping Wheeling residents healthy throughout history, check out these fascinating and complex stories of three Wheeling doctors.

Dr. Eliza Hughes

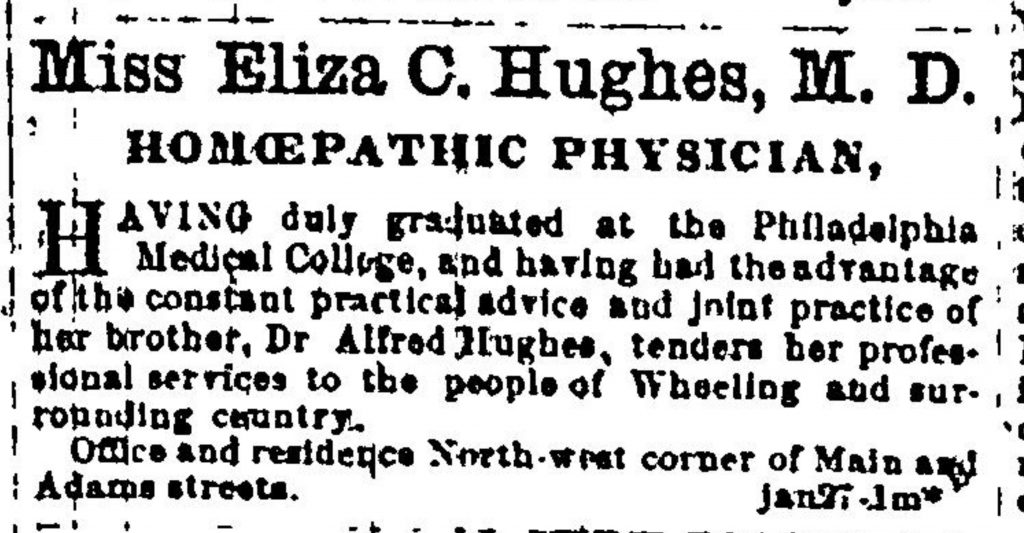

Dr. Eliza Hughes is the earliest professional female doctor documented in Wheeling and her story is full of medical intrigue, but also sensational drama. Hughes was born in Wheeling in 1817 to a prominent family.2 She graduated from the Penn Medical University in Philadelphia in 1860, at a time when women were just starting to obtain professional medical degrees and fight for their ability to practice medicine. The first woman to earn a medical degree in the US, Elizabeth Blackwell, only graduated in 1849—a mere eleven years before Hughes. Even though it was difficult, rare, and ostracizing to be a female physician during the mid-to-late 1800s, Hughes was perfectly positioned as a white woman from a prominent wealthy family—she had the means to attend medical school and a brother in the medical field to align her practice with.

After receiving her medical training, Hughes returned to Wheeling to join her brother Alfred’s medical practice in 1860. They both specialized in homeopathic medicine, a newly popular practice that prioritized more natural treatments with the belief that the body would work to heal itself.3 While working with Alfred, Eliza focused “her attention exclusively to Obstetrics and the Disease of Females and Children.” Their office was in Alfred’s home on the corner of 4th and Quincy (now Chapline) Streets.

However, the onset of the Civil War quickly derailed their practice. The Hughes family was passionately Confederate, which was a minority in the Union sympathizing city of Wheeling. Two days after the firing on Fort Sumter that began the war, Eliza wrote directly to Confederate President, Jefferson Davis, offering her medical services. In August 1861, Alfred was arrested at his home along with others, for being “suspected for signing up for the “rebel army.”” Alfred refused to take the oath of allegiance and was held for over a year at Camp Chase near Columbus, Ohio.4

Eliza herself was very briefly jailed due to her own refusal to take the oath in 1862, but according to the Wheeling Intelligencer, she “repented, took the oath and was released.” While the Civil War tensions and events in Eliza’s life were not directly medical, they did have a profound effect on her practice. With Alfred at Camp Chase, Eliza was left to practice medicine on her own. However, due to her arrest and involvement in highly publicized court cases, Eliza began losing patients.

After moving to Baltimore for a brief time after Alfred’s move out of Wheeling and her mother’s death in 1872, Eliza returned to Wheeling and was living here when she died, en-route to visit a patient, on May 27, 1882.5

Even though it is clear that Eliza practiced medicine in Wheeling, through letters, advertisements, and other testimony, she was rarely included alongside the other male physicians in Wheeling directories or other lists. For example, even though the 1864 Wheeling City Directory records Eliza’s occupation as a physician, she is not included in the business directory section with all of the other male doctors. In some of the other city directories, her profession is not listed at all.6

Possibly because she was a woman, possibly because she practiced homeopathy—which was not respected in some medical circles—Dr. Hughes is largely shut out of local medical societies of the time, such as the West Virginia State Medical Association and the Wheeling and Ohio County Medical Society. Throughout her career, Dr. Eliza Hughes was rarely seen as just a doctor—her profession was always accompanied by a gendered label such as “Doctress” or “Lady Doctor.”

Dr. Harriet B. Jones

Dr. Harriet B. Jones is often celebrated as the first woman licensed to practice medicine in West Virginia, even though Eliza Hughes was working as a doctor in Wheeling decades before Jones was even born.

Harriet B. Jones was born in Pennsylvania in 1856, but grew up in West Virginia. As a young woman, she moved to Wheeling to attend the Wheeling Female College. Almost a decade later, she graduated from the Women’s Medical College in Baltimore, Maryland in 1884. Moving to Wheeling in September 1885, Dr. Jones started her own medical practice and eventually established a women’s hospital in the 1890s. She specialized in obstetrics, gynecology, and abdominal surgery. Unlike Eliza Hughes, only a few generations earlier, Dr. Jones was able to be a member of associations like the West Virginia State Medical Association, the Ohio County Medical Society, and the American Medical Association.7

Dr. Jones’ medical influence reached much further than Wheeling. Between 1888 and 1892, Dr. Jones was the assistant superintendent of the West Virginia Hospital for the Insane in Weston (Weston State Hospital). Later in her career, she helped establish other institutions such as the Hopemont Sanitarium, West Virginia Children’s Home, and the West Virginia Industrial Home for Girls.8

In terms of public health, one of Dr. Jones’ largest campaigns was tuberculosis education. Tuberculosis, colloquially known as TB or consumption, is an infectious disease that primarily affects a person’s respiratory system. During this time, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, tuberculosis sanitariums popped up around the US to treat patients with the bacterial infection.9 Dr. Jones lobbied for these sanitariums, in addition to traveling around to at least 33 counties in West Virginia giving lectures about tuberculosis prevention. Traveling on unpaved roads in a hand-crank Ford, Dr. Jones and her companion, Frances McMahone, reached so many people that the WV Legislature allocated $9,900 in 1912 for a tuberculosis educational railroad campaign. Locally, Jones co-founded the first tuberculosis clinic in Wheeling.10

Dr. Jones’ medical accolades are only part of her story. In addition to her medical advocacy and tuberculosis education campaign, Jones was a leading suffragist in West Virginia and served as the president of the West Virginia Equal Suffrage Association during the 1906-07 term. She stayed involved in women’s voting rights through the League of Women Voters even after the 19th Amendment affirmed women’s suffrage. Dr. Jones was eventually elected to the West Virginia House of Delegates in 1924, just four years after women gained the right to vote. According to the Morgantown Post, as a “tower of political strength,” even in her retirement, she managed to successfully get every woman in Glen Dale to the polls for a presidential election.11 To read more about suffragist activities in Wheeling, click here.

Dr. Jones never married or had children, but she was heavily invested in the communities young people. She organized health examinations and pioneered sex hygiene education for school children, as well as her support for neighborhood playgrounds. As an elderly person living in Glen Dale, she created “travel clubs” for the young local boys where they could meet at her home and hear about her travels and adventures.12 Rarely known for being idle, Jones also authored at least five books including titles like: “The Health Laws of West Virginia” and “Facts Every Intelligent Voter Should Know About the Government of West Virginia.”

While not the first female doctor in Wheeling, Dr. Harriet B. Jones’ dedication to medicine, voting rights, and the wellbeing of her community has stood as an example to future generations.

Dr. J. Katherine Pronty (Davis)

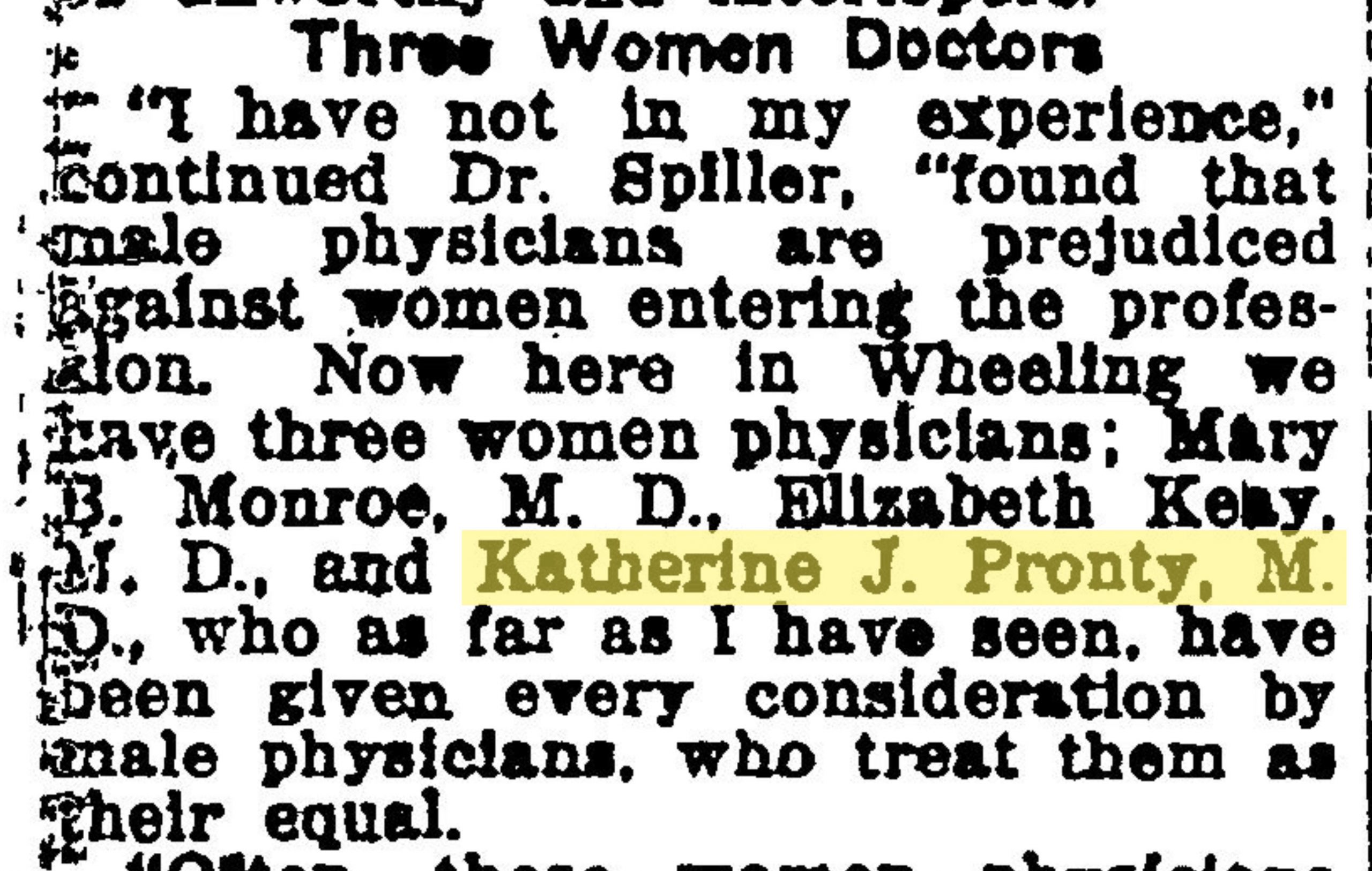

Originally from Virginia, Dr. J. Katherine Pronty was not born and raised in Wheeling, but she came to the city in 1911 to start her first medical practice shortly after receiving her M.D. and passing her medical exams.13 Dr. Pronty graduated from Meharry Medical College, in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1910.14

She kept a home office on 11th Street in what was the center of the vibrant African American neighborhood at the time. In addition to general medical treatments, Dr. Pronty is also noted for delivering babies and administering prenatal care for expectant mothers. She is included in the list of physicians by the Wheeling Health Department who reported monthly birth statistics in the Wheeling Intelligencer.15

Even though she did not grow up in Wheeling, she was joined by members of her family in the city, including her sister, Mattie, who taught at the Lincoln School.16 In 1919, Dr. Pronty married John H. Davis, who was a pharmacist at the North Side Pharmacy.17

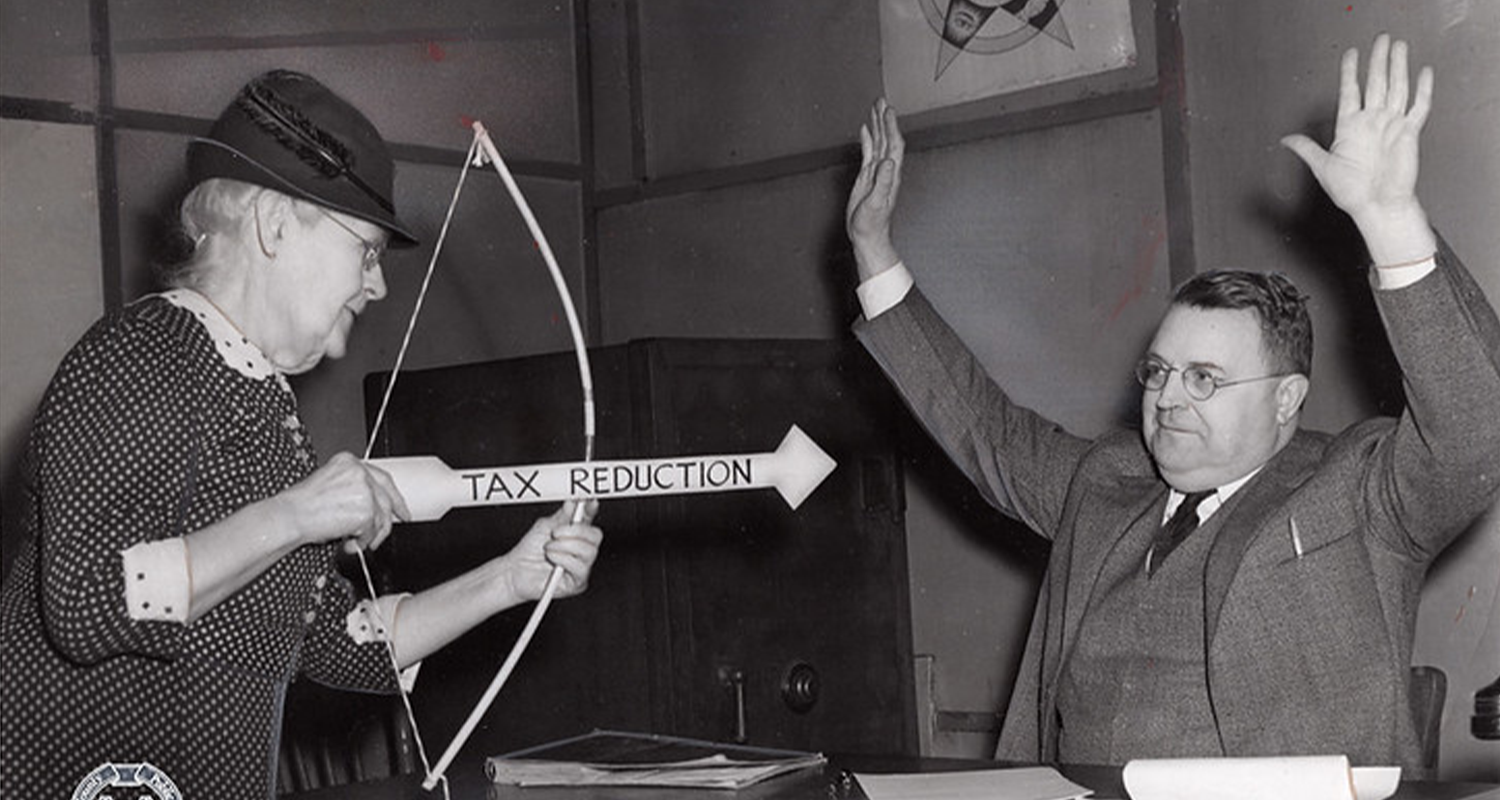

In 1927, Dr. Pronty is listed as one of three women physicians working in Wheeling in a Wheeling Intelligencer article by the Ohio Valley General Hospital Superintendent, Dr. H. F. Spillers. Even though Dr. Spillers was declaring that women could be just as effective physicians as men, his comments reveal the sexism that Dr. Pronty and others still had to contend with. For example, he explained that the reason that women did not become surgeons “is not because they are not capable and lack ability to do the work, but because they cannot get rid of their dread of blood.”18

In addition to her medical practice, Dr. Pronty was also involved in the community. During the annual “Negro Health Week,” Dr. Pronty would give public talks, with topics such as “Prenatal Care.”19 Most notably, she was a member of the Ladies Auxiliary of Post 89, which was the women’s companion branch to the historic Black Legion Post 89 in Wheeling.20

In addition to being a woman in a male-dominated professional medical field, Dr. Pronty also ran up against racial barriers and racism. She was practicing medicine during the height of Jim Crow segregation that was clear and ever-present in Wheeling. Only a few years after starting her medical practice in Wheeling, Dr. Pronty was assaulted by a white man in Downtown. Despite being intimidated by the police, Dr. Pronty pressed charges and the man was found guilty—yet served no jail time and was only fined $10.21 There are other accounts throughout her career of Dr. Pronty being the first medical person on the scene during racially-motivated incidents or assaults. For example, in September 1921, when Charles H. Moore, a Black man from the Fulton neighborhood was beaten by five white men while walking in Downtown, he called Dr. Pronty.22

Dr. J. Katherine Pronty Davis died on September 6, 1949 and is buried at Stone Church Cemetery.23 As an important part of her identity, “M.D.” is etched after her name on her tombstone.

Paving the Road

While each of these doctors worked in Wheeling during different times with distinct practices and attitudes towards women in the medical field, they built upon those who came before them. Drs. Hughes, Jones, and Pronty delivered important healthcare and medical services to the people of Wheeling, persevering through varieties of sexism, and for Pronty, racism. These three featured women were not always respected in the Wheeling medical world, but they paved important roads for the future female doctors that have come, and will continue to come, after them.

Special thanks to Margaret Brennan for her knowledge and research guidance about the history of female doctors in Wheeling. Additional acknowledgement to Sean Duffy and Erin Rothenbuehler for their original research into the lives and work of Dr. Pronty.

• Emma Wiley, originally from Falls Church, Virginia, was a former AmeriCorps member with Wheeling Heritage. Emma has a B.A. in history from Vassar College and is passionate about connecting communities, history, and social justice.