If you celebrate Easter, then you already know that a trip to the local grocery store for eggs and a dye kit is expected in preparation for the holiday celebration. But apparently not for everyone. As I was perusing the local digital newspaper archives (as one does), I came across a silly snippet that felt too timely not to share.

The headline read: “Inmate Gets Easter Eggs, Then Leaves.” With such an attention-grabbing title, who wouldn’t be persuaded to read on?

As it turns out, on April 12, 1968, an inmate who was being held at the West Virginia Penitentiary was given a work assignment at the prison’s chicken farm. This must have afforded him some time away from the watchful eye of the guards because he took this opportunity to make an escape, but not before collecting some eggs on his way out. The article claims that“[the] inmate apparently got his Easter eggs early, then scrammed.”1 This crime shouldn’t have come as a total surprise, as the article also notes that this person was already serving a short sentence for breaking and entering.2

Unfortunately, that’s where the story ends for the penitentiary’s Easter egg escapee. However, this quirky story did inspire a quick look at the role that farming and other trades played at the West Virginia Penitentiary during the years it was in operation.

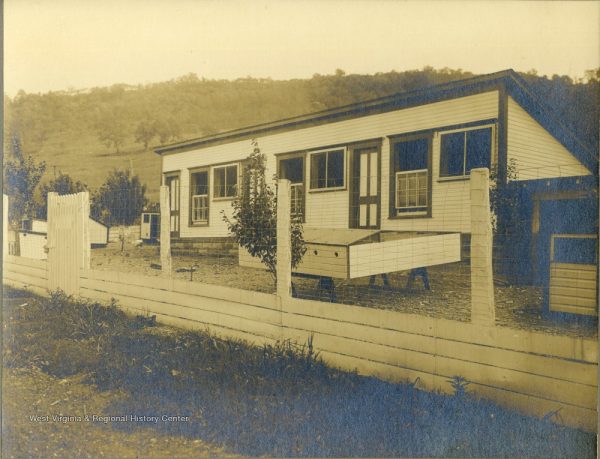

According to the National Register of Historic Places Nomination for the West Virginia Penitentiary that in addition to a poultry farm, the penitentiary also operated its own blacksmith and wagon shops, carpenter shop, brickyard, stone yard, paint shop, shoe shop and tailor shop. Originally, the prison had a 10-acre farm that was later relocated to a larger, 200+ acre space where fresh produce was grown for use in the facility’s kitchen and preserved for later use. 3

The people who worked in these trades were a part of the trusty system that provided certain privileges to inmates in exchange for their work. While there is plenty that can be said about today’s prison industrial complex and the unfair work practices associated with it, at the time, the West Virginia Penitentary’s trusty system provided work and a sense of accomplishment to those who participated.

So, whether you get your eggs from the grocery store or sneak a few from your neighbor’s backyard chicken coop, we hope you have a happy and crime-free Easter.

References

1 “Inmate Gets Easter Eggs, Then Leaves.” The Intelligencer. April 12, 1968.

2 Ibid.

3 National Register of Historic Places, West Virginia State Penitentiary, Moundsville, Marshall Co., West Virginia, 10024-0018