(Writer’s Note: This is the second in a series of stories that will concentrate on the history of one of the most storied restaurant franchises in Wheeling since the 1950s.)

They wanted to try roller-skating waitresses, those Boury brothers did, and they even attempted it for a very brief time at their first Elby’s, but curb service in the end was still a tray-on-window experience that was very popular in the late 1950s and 1960s.

Then the trend redirected toward the eat-in experience, and that’s where “the rules” really set in. There were many standards established that concerned recipe guidelines, and other service-related requirements that would be impossible to implement today because of the current work ethic as compared to when an Elby’s Family Restaurant rested in more than 70 different communities in Ohio, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Maryland in the 1970-80s.

The servers were mandated to have their shoes polished, their uniforms clean, any tattoos hidden, and only one ring on each hand was permissible. Waitresses were not permitted to wear nail polish, they had to have their hair pulled back, and they were permitted to wear only one pair of earrings. Waiters could have a mustache but not a beard, and they had to be clean shaven when reporting to work. Facial piercings were not acceptable, period.

Those guidelines, though, allowed three first-generation American brothers to own and operate the most successful Wheeling-based restaurant chain in the history of this Friendly City.

If pressed to offer an estimated number of total employees that Boury Enterprises employed between the opening of the first Elby’s in Wheeling to when the brothers sold the chain of 76 eateries to Elias Brother Inc., Gregg Boury’s guess was, “A little more than 100,000.”

At the corporation’s absolute peak, Boury said, Boury Enterprises possessed a grand total of 6,800 employees.

Each Elby’s was staffed with busboys, servers, salad preppers, dish washers, food preps, short-order cooks, one assistant manager, one manager, and then during the 1980s, the breakfast/salad bar attendants. On the ladder above were district managers and service supervisors, and then on the level just below the Boury brothers was a man named Tom Johnson, a Valley native who was hired only five years after the first Elby’s Big Boy opened in Wheeling in 1956.

“Tom was as meticulous as anyone in the company was, and that includes my father and his brothers,” said Boury, one of four children reared by co-founder George Boury. “He was adamant that our formula was followed, whether it involved the labor, the production, or customer interaction. He set that bar really high, and that translated down to the district managers, and it continued spreading from there.

“Tom, for as long as I recall, was always present, and I always saw him, but we didn’t start working directly with each other until the last decade or so,” he recalled. “And Tom always had the same attitude about the job. There was only one way to do it, and that was the right way.”

Bill Bryson, the marketing director at Boury Enterprises for nearly two decades, recalled Johnson vividly as the conduit between the restaurant chain and George, Mike, and Ellis. Johnson, he says, was the hammer that would come down hard but without inflicting pain.

“He was the guy who went from restaurant to restaurant to set the standards. He delivered the rules, and if he noticed those rules were not being followed, he would communicate that to the district supervisors,” Bryson recalled. “He was hands-on, and when Tom chewed you out about something, he had a way of convincing you that he was right.

“For whatever reason, you knew that you had been chastised, but boy, you couldn’t wait to fix it to make Tom proud of you,” he continued. “He was tough, and he came from the other side of the tracks, but I believe he won the respect of the brothers and of all the employees in the company because of the way he went about what he did.

“Tom was the glue between the restaurant side and the Boury brothers. He always made sure their wishes were followed because he wanted to make sure that he was doing his job and that the Bourys would be proud of him.”

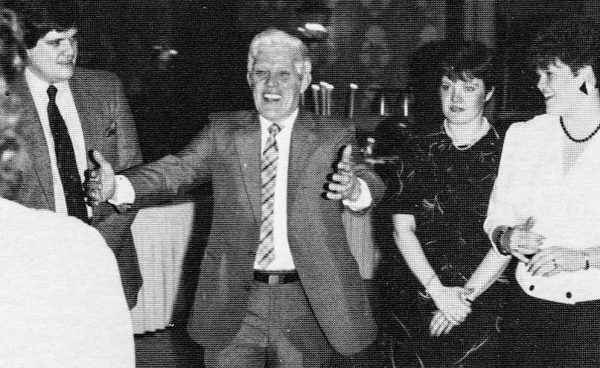

Johnson was honored for his 25th anniversary with the company in 1986, the same year Elby’s celebrated its 30th year in business.

“There is no question that he was an integral part in the success and the growth of Elby’s. He was demanding, but he was fair, and most importantly, he was consistent,” Boury said. “He expected the same tomorrow as he expected today, and what he expected from the employees in Columbus, he expected the same here in Wheeling.

“There weren’t any surprises when it came to Tom Johnson. He had a drive and an energy level that were through the roof,” he continued. “His approach was contagious, thankfully, and that’s because of how he went about his duties for many, many years.”

Those Nine Steps

The process was simple for the customer and the server. The customers walked in and were greeted by the hostess; the hostess then led the customers to an available table; and that’s when the nine steps took over.

- The server is to approach a table within one minute of their seating with waters for all guests and collect their beverage orders.

- After delivering the beverages, take their orders while using suggestive selling.

- Turn the order in to the kitchen.

- Return to table to deliver all necessary setups and condiments, as well as the cole slaw or the dinner salad, to the table.

- Serve hot food hot and cold food cold – the servers were expected to pay attention to the number system that hung upon the kitchen areas and to the short-order cook’s window.

- Check back with the table a few minutes after the meal is delivered to make sure everything is OK; check for drink refills; remove any dishes.

- Return to the table to place the check on the table, and let them know you will return shortly.

- Dessert anyone? Hot Fudge Cake? Strawberry pie?

- Either deliver desserts or return one last time to deliver the final check and remove all empty dishes.

“The funny thing about that nine-step process is that if you do number one, a lot could be forgiven after that. If the server got right to that table as soon as those folks sat down, all the steps that were to take place after that could have a little flexibility because of how much it means to the customer to be acknowledged by their waiter or waitress,” Boury said. “It was very important for the employees to get that first step right.

“And I really do not know who developed the nine steps, but at Elby’s we demanded 100 percent compliance to them,” he continued. “The nine-step process was The Bible for Elby’s, and it made it easier for the servers because it really broke it down to the basics. Serving a table is a difficult process if you think of everything that goes into it, but those steps really spelled it out.”

Every Elby’s employee was mandated to attend a training session to learn those steps and also to gain an education about the ingredients, the process, and the expectations. Twenty-two ounces of strawberries in each pie; two-and-half squirts of hot fudge; and no, the Big Boy does not come with tomatoes on it.

“All of it fell in line with the attention to detail, and the training was very important if not the most important aspect of working at an Elby’s,” Boury explained. “The customer-employee interaction was critical to the success of the restaurants. And it had to be consistent. There had to be consistent service and consistent food quality so a customer’s experience was consistently a very good one.

“And that was imperative across the entire chain of restaurants,” he continued. “My dad said one time that if you ate breakfast at an Elby’s in Columbus, and then you drove to eastern Pennsylvania and ate dinner at an Elby’s there, he wanted you to have the same kind of experience at both restaurants.”

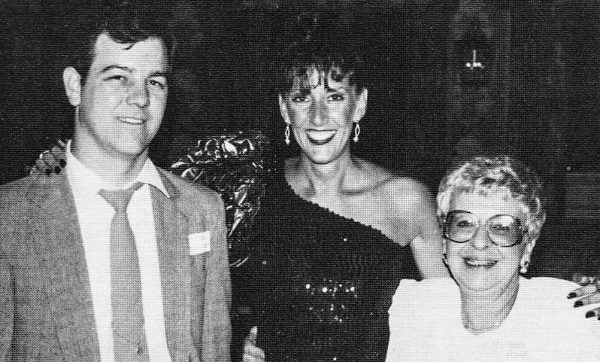

Donna Holmberg began her career with Elby’s in 1976 as a part-time waitress at “No. 6,” the Big Boy located near the Ohio Valley Medical Center and Wheeling High School. She worked some curbside but mostly inside, and when she was close to quitting because she started working at a Wheeling photography company, she decided to work both jobs.

“I stayed on at Elby’s because I didn’t want to disappoint my manager, Rick Anderson. Then my district manager, Dan Connors, told me he thought I would make a good supervisor,” recalled Holmberg, now a district merchandiser with the Kroger Company. “But after that I quit my job with the photography studio, and I went full-time with Elby’s. I had a company car, and I would travel to 12 different stores in the beginning to check on service procedures, the processes involved with human resources, and the appearance of our staff members.

“There was a way to go about it and a way they were supposed to look, and there weren’t exceptions made,” she said. “The rules were the rules, and when they were followed, people made more money. That I knew was true.”

“Donna was the quintessential Elby’s employee,” Boury reported. “She was the front-of-the-house model for the way things should be done. She was as meticulous as anybody in the company, and she took offense if anyone violated the nine-step process.”

Those nine steps. It’s a formula for serving tables that is universal, really, because it makes so much sense. Communicate with the customer; deliver the food soon after it is prepared; keep beverages full; and suggest some pie near the end.

“That’s the way the Boury brothers felt about the quality of their service, and if there was a breakdown with one of those steps, you’ve skipped something for your customers,” Holmberg explained. “I know I was very strict about those nine steps because of what they meant to the customer experience at an Elby’s.

“When I would notice a waiter or waitress skip a step or go about one of them in an incorrect way, I definitely would say something to them at the time so they could fix it for their customers,” she continued. “I had to address it immediately so providing the wrong service to the customers didn’t become a habit for a particular server and the entire staff.”

Once promoted to Service Director for the entire chain of Elby’s, Holmberg was always on the road bouncing from location to location because it was Johnson and she who were charged with the inspections so the Boury brothers could concentrate on continued expansion. Before tendering her resignation, she assisted with opening 48 of the family-style eateries.

“My dad and the brothers didn’t travel to the other stores very often unless there was a specific reason,” Boury explained. “Otherwise, they depended on the network of supervisors and managers that they put into place, so what I used to tell my employees was that if they were going to make a mistake, make it while waiting on George Boury because I know he’d come back and eat again.”

A number of uniform changes occurred over the years, so it was certain current-at-the-time fashion trends were followed to ensure the customers were as comfortable as possible when visiting Elby’s.

“I believe the uniform ideas initially came from the Big Boy franchise because that was the fashion for a family restaurant at that time. There were a few different choices, and then my father, his brothers, and the upper management people would review them and choose what they thought would work best in the areas where they had Elby’s,” Boury explained. “I can remember the fashion shows that they had in the office. They had options, and they collected as much feedback as they could get before making their choices.

“Most people may not realize it, but the brothers always collected opinions,” he continued. “Sure, the final decisions were theirs, but they wanted to know what others thought before making them, and the uniforms were not different.”

A Waitress Named Flo

It was not uncommon for Elby’s employees to remain with the company for years and years, and they recall everything from their favorite customers to the time when the boys would go off to Vietnam but would never return.

Flo McNickle is no different. As a 25-year veteran, she felt like a family member.

McNickle began her career at the Elby’s in Weirton in 1965, and in the very beginning she was a curb-service waitress.

“It was always interesting, but it was always very cold in the wintertime; that I definitely remember,” McNickle confirmed. “I never really understood why the people would want to stay in their cars instead of going inside the restaurant, but it always seemed very popular.

“After the people would put their order over the speakers that were at each parking space, I would take their drinks to them, and then when the food was ready, we would hang trays off of their car windows,” she recalled. “They would hook down in the area where the window was, and the people would eat off of those trays.”

Her late husband, Harry, was working as a short-order cook at the Weirton store at the time, and before long the two were dating and then decided to wed.

“He was from the Wheeling area, but he was a cook at the Weirton Elby’s and that’s how we met,” McNickle explained. “After we got married, I got pregnant in just a couple of months and, that’s when we decided to move close to Wheeling.

“Except when I took time off to have my kids, I worked at Elby’s from my first day in Weirton until they closed,” she said. “I liked the company because it was run the right way, and we were almost always busy.”

A couple of years later she returned to work at Elby’s at the location on 12th and Chapline streets in downtown Wheeling. As a North Wheeling resident at the time, she would walk to and from the family’s home.

“We were always crowded when there was a big movie playing at the Court Theater and also after the Wheeling Central basketball games,” McNickle remembered. “We would have a lot of young people on those nights, and we had a lot of Central students at lunchtime, too.

“I worked mostly day-turn and I had a lot of regular customers that would come in almost every day during the work week,” she said. “And then when the restaurant moved down the street to 12th and Market, I continue working there for a lot of years.”

Flo could not recall each of the nine steps and admitted that it would take some thought before being able to list them in order. But she remembered one thing – she knows she followed them and enforced them as a head waitress.

“The system worked, and once you did it so many times, you got used to it, and it was because of the way you went about it all of the time,” McNickle said. “It got to be automatic for me. It got to the point to where I didn’t even think about the nine steps because I just did it that way and that’s how we trained the new servers.”

While some of her memories have faded over the years, McNickle is still able to rattle off items on the Elby’s menu.

“I always thought the food made my job pretty easy because it was really good and I remember eating a lot of strawberry pies,” McNickle said. “The people really enjoyed the food; I can tell you that. It was very seldom when one of my customers had a complaint about any of the food.

“There were a lot of people who loved the Big Boy, the Slim Jim, and the Brawny Swiss, but the spaghetti and the fish was really popular, too. And then there were the dinners like liver and onions and the ham steak. Those were very popular, too,” she continued. “And I can’t forget the hot fudge cakes. They loved those for sure.”

There were many more good parts of the job than aspects she did not enjoy, McNickle says, but some of the side work assignments were not something she fondly recalled.

“I enjoyed most of it but every job involved things you didn’t like, and for me it was the amount of cleaning I had to do,” McNickle chuckled. “There were some days I felt like I was working in housekeeping instead of being a server.

“The best part was all of the people I got to meet, both the people who worked there and the customers,” she said. “There are a lot of those people who I still talk to because of how long we all worked together.”

Flo recently celebrated her 70th birthday, and many of those former co-workers attended the party staged by her daughter at Quaker Steak & Lube at The Highlands.

“It was like a family, but I was really shocked when I saw how many of them came to wish me a happy birthday,” she admitted. “It was amazing, and it was like an Elby’s reunion. Almost everywhere I looked more and more memories came rushing back because of the people who were there.

“I guess that just goes to show you how it was back then,” McNickle explained. “It’s an example of how we still feel about those years and about the people we used to work with. I know I still talk with a lot of the girls that I worked with every day because we became friends and not just co-workers.”

Flo McNickle still works in the waitressing game as a three-days-a-week server at Cracker Barrel near the Ohio Valley Mall in St. Clairsville. After the Big Boy business collapsed, she gained employment at Endsley’s in downtown and remained there until former Elby’s manager, Terry Endsley, closed the restaurant in 2008.

She is aware that her first place of employment still stands today along Freedom Way in Weirton, but she refuses to get close enough to peer inside the windows.

“I always see the sign and the old building when I travel through Weirton, and I’ve always thought that is was a shame it closed with all the others. I’m surprised whoever owns the building has never done anything with the property since.

“I’ve not stopped to look at it, and I’m not sure I would want to. It’s was too good a thing, and to see it just sitting there like that makes me sad every time,” she said. “I’ll just keep the memories that I have because I loved that job. That’s why I stayed there for so long. It’s what many of us did.”

Made for Marketing

Bill Bryson did not prepare the food, nor did he serve it, but as the company’s vice president of marketing, one of his duties was to promote the people following the strict service standards.

Bryson first gained employment with Boury Enterprises in 1981, when he was hired as the general manager of four of the Gift Shop/Factory Glass Outlets. In December 1982, though, he was offered and accepted the position of Director of Marketing for Elby’s Family Restaurants.

“What I remember as far as the employees were concerned is that there was always that ‘team’ atmosphere, and it started with management and filtered down from there,” said Bryson, now the owner of UniGlobe Travel in downtown Wheeling. “It all started with the Boury brothers; then it went through Tom Johnson, and then to the district supervisors, and so on. It seemed like everyone was pulling for the same thing.

“There was a lot of pride involved, and the brothers realized, I believe, that they were the ones who touched the customers the most,” he continued. “It was a great system that was in place, and it worked. It really did.”

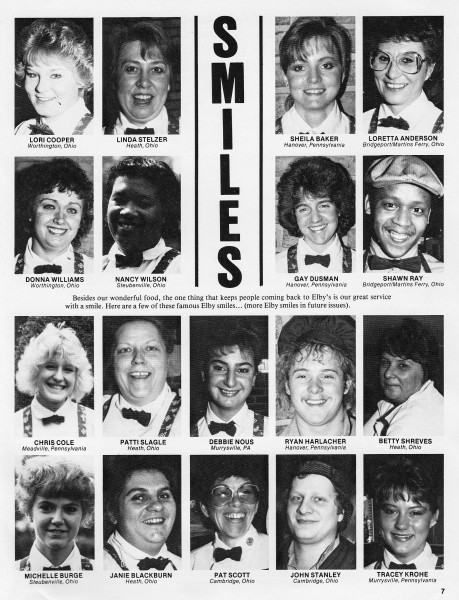

Bryson was charged with producing a 32-page company-wide newsletter that was distributed to every single employee. Performance statistics, family news, restaurant openings, new management hires, engagements and weddings, births, promotions, parades, and the distance race were all covered with a few words and a plethora of photographs.

All publication space but a half-page on the inside cover was dedicated to the employees at Boury Inc., TriAd, the commissary, and at the restaurants and hotels.

“The brothers started creating and distributing that newsletter primarily so they could further recognize their employees because they really believed they deserved it,” Boury recalled. “I can remember when one of the newsletters would arrive at the Elby’s where I was working at the time, and every single employee wanted to see if they were in it or if their store was in it. It was a big deal to them.”

The marketing director still recalls his meetings with George, Mike, and Ellis, and when the topic of the newsletter was addressed, the brothers were usually pleased but consistently wanted more.

“From the top down, the owners and those in management appreciated their employees tremendously, and I was involved with two special things while I was with the company,” Bryson recalled. “Every quarter we would do the magazine, and I can remember the brothers telling me, ‘More pictures! More pictures!’ We got to the point to where the only way I was going to be able to get more pictures in it was if the number of pages increased.

“Every chance we got we would take a picture of the people who worked for the chain so they could see that they were a key part of the organization,” he said. “The only space that wasn’t necessarily about the employees was right on the inside cover of every one of them, and on that page one of the brothers or Tom (Johnson) would write a note to everyone in the chain. My instructions were to make everything else in those newsletters about our employees.”

Bryson was also involved with organizing celebrations for the employees during which awards were given for employment anniversaries beginning, he said, at three years.

“The people looked forward to those banquets, and I think there were some employees that stayed as long as they did because of how much they appreciated those banquets,” he said. “I remember a lot of employees would travel to Wheeling and get hotel and motel rooms just so they could go to them and that’s because the brothers really didn’t spare much expense.

“It all played into the ‘team’ thing we had there, and that’s because the Boury brothers and Tom Johnson always recognized just how important every employee in the company was,” Bryson said. “And it was real. Sure, there were rules, and those rules were enforced, and in the position I was in, I got the chance to see both sides of it. I know what they wanted me to do as the marketing director, and then I got to see how the restaurants were operated and why they were operated the way they were.”

“The Boury brothers went all out for us because they were three small-town men who wanted to take care of their people,” Homberg added. “That’s what it was and it’s something you don’t see anymore.”

The brothers opened “No. 1” on National Road in 1956, and then “No. 2” opened in Moundsville a few years later. Success came quickly, and the Bourys soon constructed Elby’s in St. Clairsville, downtown Wheeling, Weirton, Center Wheeling, Steubenville, and many more until six districts were well established in four states.

The banquets continued until the sale of the chain to Elias Brothers in 1987, and since Bryson accepted a similar position with the new company, the newsletter distribution continued until Elias decided to close down the eateries just a few years later.

The food was different under Elias Brothers, and many changes continued all the way down to the coffee. No longer was the Big Boy brand synonymous with what Elby’s had provided for more than three decades.

“In the end, everybody was blaming everybody else, and there were no winners at that time, and that’s a shame because there were a lot of winners during those first 30-plus years,” Bryson said. “A lot of people raised families by working at Elby’s, and then those kids got jobs there when they reached the age. There were a lot of winners through the years; there really were.”

Weelunk.com publishes daily, to receive notification of new stories like this one, be sure to like us on Facebook here: Weelunk