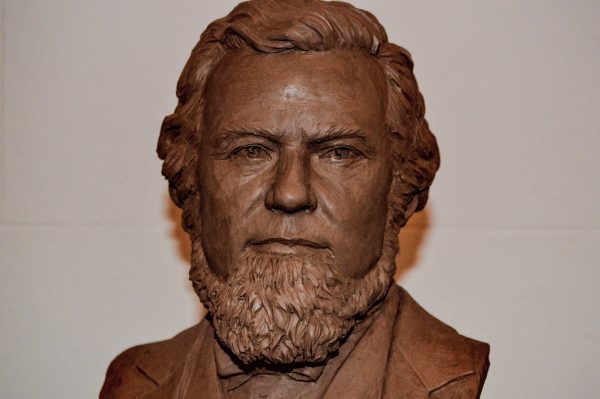

He’s a 9-foot bronze man, and he is the father of West Virginia.

The installation of the statue of Francis H. Pierpont is set for today – West Virginia Day – at noon on the corner of 16th and Market streets in downtown Wheeling in front of the West Virginia Independence Hall.

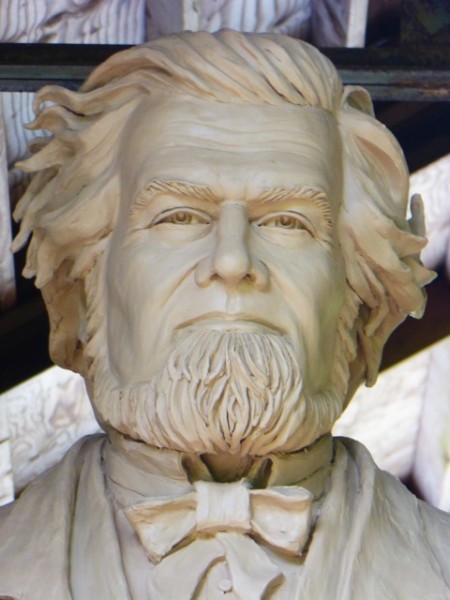

The statue represents the first public monument to Pierpont in the Mountain State and is the result of a $135,000 project that started three years ago by the Wheeling National Heritage Area Corp. Under the guidance of the Francis H. Pierpont Statue Committee, the project received support from the city of Wheeling, the Ohio County Commission, the state Senate and House of Delegates, and numerous private donors. Wheeling Heritage commissioned sculptor Gareth Curtiss of Montana in 2013, and the sculptor’s design shows Pierpont holding a copy of the U.S. Constitution.

Curtiss, Wheeling Vice Mayor Mayor Gene Fahey, U.S. Rep. David McKinley, Independence Hall site manager Travis Henline, Executive Director of the Wheeling National Heritage Area Corporation Jeremy Morris, and a representative of the Pierpont family will address those who gather for the unveiling.

The one and only problem, according to Henline, is that Pierpont is not that well known among current West Virginia residents.

“After everything he accomplished, not many people know who Francis is. That blows my mind. It really does,” Henline said. “I have large groups of West Virginians here (at Independence Hall) for tours, and I would ask them if they knew of anything about Francis Pierpont, and no one ever knows anything about him. It makes me wonder how so few West Virginians know anything about him although he is the father of the state.

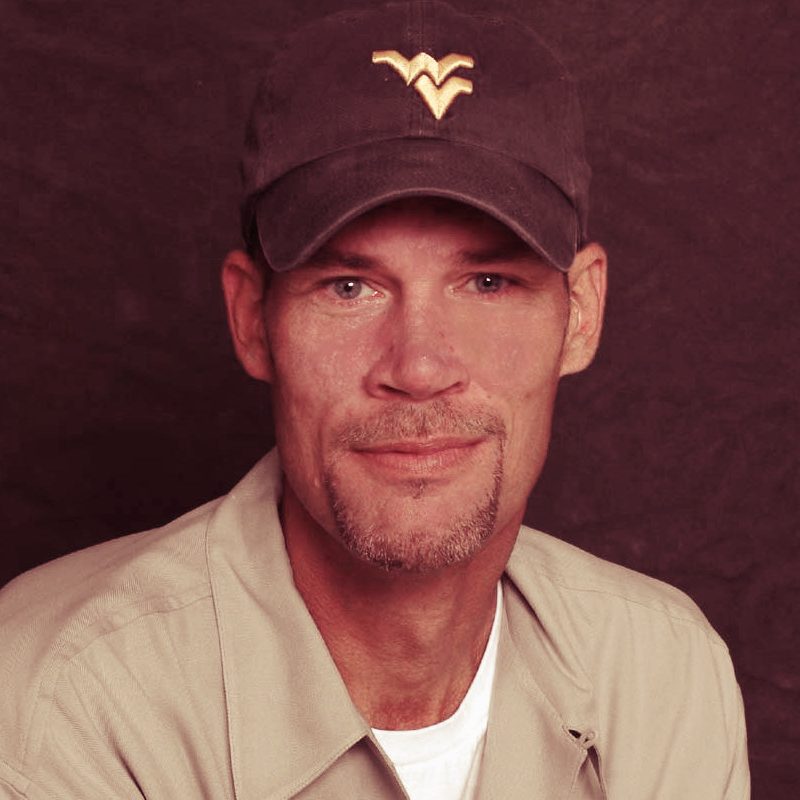

So, when searching for Pierpont’s story, who better to ask than Henline, the same man who will portray him during today’s unveiling ceremony?

“One of the things that I admire so much about Francis Pierpont is that he came from humble beginnings,” explained Henline. “His father was a tanner, so he worked with leather goods. That’s how his father made a living, but you don’t get real rich as a tanner.

“That is why Pierpont was self-educated for the most part as a young man while learning the tanning trade and working on the family farm,” he said. “The majority of the people from eastern Virginia saw themselves as coming from families they believed were part of the American aristocracy. They were from a privileged class, but not Francis Pierpont.”

Pierpont was born in Monongalia County in 1814. When Francis was still a young boy, the Pierponts moved their leatherworks business to Marion County. While he did attend class in a one-room school to learn reading, writing, and arithmetic, Francis was mostly self-educated, according to Henline. Once he reached the age to attend college, he enrolled in Allegheny College. Upon his graduation, Pierpont moved home and began his teaching career in Harrison County.

After a few years, Henline explained. Pierpont took a job offer in Mississippi, and that experience changed his outlook and opinion on America at the time.

“That was big in Pierpont’s life because for the first time in his life he is living with the institution of slavery as it was in the southern states,” Henline said. “He’s in one of the plantation states, and slavery is right in his face. He sees for himself how nasty and how cruel the system really was.

“People who knew him at the time he came back from Mississippi said he returned as an abolitionist because of what he witnessed there,” he said. “At that point in his life he got back into the tanning business, but he also started reading the law. That’s what you did back then under the tutelage of a lawyer so you could become an attorney. And he did pretty well because he became the general counsel for the B&O Railroad in Taylor and Marion counties in 1848.”

Not only was Pierpont pleased to be out of Mississippi, but after earning good money as an attorney, he also became an entrepreneur by purchasing a coal mine in Marion County.

“And Francis Pierpont was a very devout, spiritual man, and he was very involved with the Methodist church at that time,” Henline said. “If we did not remember Francis Pierpont as a war-time governor during the Civil War who became the father of our state, we would know him in history as one of the main players with the reforming of the Methodist church.

“He was a man of God and invoked God in many of his speeches,” he continued. “That is very important to understand about him because of the ways he went about becoming the founding father of West Virginia.”

Pierpont commented on the political landscapes in the state and throughout the country via letters to newspapers, but never did he consider anything more than speaking as a free American. But then he became familiar with the effort to separate from slavery again with the possible secession from the slave state that was Virginia.

“Francis Pierpont was never a politician until he had to be,” Henline said. “That is an incredibly important point to make. He never ran for an elected position. He was vocal about politics in his day; he would write to newspapers about the conditions he saw in the southern states, but those were just pieces in the paper.

“I don’t think the man ever really thought of himself as a politician, but he did have a way of being savvy when dealing with people. He knew how to handle people,” he said. “And then everything changes for him with the coming of the Civil War because the first votes about the possible secession from Virginia came back not in favor of separating from Virginia. He was the one who swung opinions the other way.”

Those in favor of the separation held a convention in Wheeling in 1861, but little organization was present, and that meant little was accomplished to forward the secession plan. But that’s also when Pierpont, who was in attendance, went to work.

“There is a story about Francis Pierpont reading the United States Constitution in his study at home in Fairmont, and then his wife heard him say, ‘Eureka. I’ve found it. I’ve found it,’” Henline said. “What he had found was the plan. He knew how to go about it at that point.

“He came across some of the sections of the Constitution that gave him the basis for the formation of the restored government of Virginia, and the idea for the way in which a new state could be created. In one section he found the guarantee that each state would have a Republican form of government that would protect them from invasion and from domestic violence,” he said. “He also found the section that speaks to the formation of new states, and it states that to create a new state from a parent state, the legislature from the parent state and the U.S. Congress had to give permission for it to take place. He knew he had found it. He found the mechanism that they were going to use to pursue a new state.”

Francis Pierpont was 48 years old at the time.

“He would probably tell you that providence placed him that situation,” Henline said. “So he attended the second Wheeling convention and he presents his plan, and then it was discussed and then adopted, and they decide that they are going to form this new government. They decided to go for it with no idea as to how it would go.

“Pierpont referred to it as, ‘the fearful experiment,’ and fearful is the operative word because of everything these men had to lose,” he said. “The confederate governor of Virginia put out a call for their capture, but they moved forward anyway and Pierpont was unanimously elected the governor of the reformed state of Virginia. He felt it was his duty to do the things that he did. The one word that I think people should associate with Francis Pierpont is, ‘duty.’”

Suddenly, Pierpont found himself of raising the funds necessary for war, and then he was the man who was commissioning officers and sending supporters off into a brutal, deadly war.

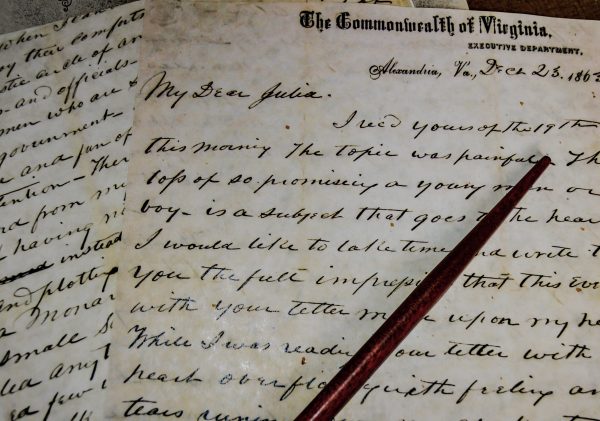

“When you review his papers most of the correspondence involves war-related issues, and this was the man who was responsible for sending men off to fight. When you read his letters to his wife, Julia, you can tell that it weighed heavily on his mind,” Henline said. “He was sending these men off to war, and that also meant that he was sending men off to die.

“He could see these young men from his office window. He saw them parading down the street to load onto the railcars. And then they would go off, and he knew that many of them would never come back,” he continued. “He felt that, and I believe that comes through in his letters to his wife.”

Pierpont’s role allowed him to meet President Abraham Lincoln on many occasions, and Henline said he believes Pierpont had some influence.

“Pierpont was influential with President Lincoln’s thinking when it came to statehood, and Lincoln stated that himself,” Henline said. “Pierpont’s influence was bigger than what a lot of people realize.

“Francis Pierpont could have been the first governor of West Virginia, but instead he felt it was his duty to see it through as the governor of Virginia,” he said. “And after the war, he rebuilt the government in Virginia.”

On June 20, 1863, the United States welcomed its 35th state, and Francis Pierpont was the governor of the restored government of Virginia.

“Francis Pierpont understood that there needed to be continuity, or it would have all fallen apart. If it was disrupted and there wasn’t a restored government after the war, then it would have discredited the creation of West Virginia,” he said. “What would that have said about the legitimacy of West Virginia if the government that created it would have fallen apart?

“He understood that. He knew the restored government could not dissipate. It was his duty to carry it through,” Henline explained. “He was compelled by providence and duty to go into Richmond while it was still smoldering so he could be established as the Union governor of Virginia. That took courage. He had been at peril for many, many years, and he had to move his family around because they attacked his properties, and in the middle of it all he lost a 4-year-old daughter.

“And Virginia was lucky to have Pierpont as their governor. He was fair, he was equitable during reconstruction, and he earned the respect of many people. He was very in line with Lincoln’s idea of reconciliation. He knew healing had to take place.”

Pierpont passed away on March 24, 1899, at the age of 85, and his grave is next to his wife’s in Woodlawn Cemetery in Fairmont.

Today, Francis Pierpont begins a new life in Wheeling.

photos by Steve Novotney