By Steve Novotney

Weelunk.com

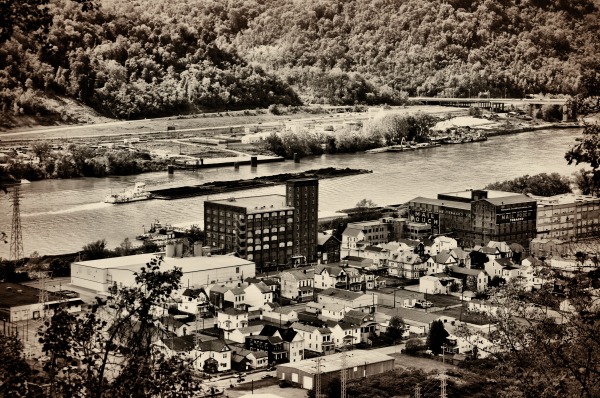

As the debate concerning the transportation of fracking waste on American rivers continues, local officials confirmed that several hazardous and non-hazardous materials already float past the Friendly City every day of the year.

According to Lou Vargo, director of the Ohio County Emergency Management Agency, mined coal accounts for the majority of what is transported on the river, but other materials include chlorine, propane, natural gas, and caustic soda.

Caustic soda, or sodium hydroxide, is used in many industries, mostly as a strong chemical base in the manufacturing of pulp and paper, textiles, and cleaning supplies. If this hazardous material is diluted with water and dripped once onto the human eye, the result would be instant blindness.

“If a load of 480 tons of caustic soda leaked into the Ohio River, it would be an ecological disaster, but that would have to be a catastrophic accident with a barge striking one of the bridges or something like that, “Vargo said. “How far down-river that impact would extend would depend on the concentration of the product that’s being shipped. Cincinnati? Louisville? All the way to New Orleans? It’d be anyone’s guess.”

Dr. Ben Stout, professor of biology at Wheeling Jesuit University, explained a few factors that would determine the total impact. “My hunch is it wouldn’t be that bad except during low flow. The travel time between Pittsburgh and Cincinnati would be about 100 days at these flow levels,” Stout said. “My main comment to the Coast Guard was to do a risk assessment concerning everything that’s allowed to float by this valley.”

Wheeling’s city manager, Robert Herron, said he and city officials are aware of what products are transported past Heritage Port and Wheeling’s freshwater intake facility in Warwood.

“Any type of accident that would impact the water quality of the river could impact the quality of our water supply, but the city has no jurisdiction over what goes up and down that river,” Herron said.

“But I feel confident that the Coast Guard and the Army Corps of Engineers have put into place safety measures that allow what does go up and down it. And if something like that were to happen, the fire and police chiefs would be the ones to handle it, and I have complete confidence in the both of them.”

Vargo remains uncertain as to when the U.S. Coast Guard will render an official opinion pertaining to the transportation of fracking waste on American rivers, but if it is approved, he will not be surprised. Barges chugging on the Ohio River have been a common sight in the Upper Ohio Valley for decades, and they still are today with as many as 5,000 carriers per year transporting a number of different materials north and south on the historic waterway.

Vargo reported that at least 65 million tons of coal are river-transported through Ohio County each year. Raw materials represent 7.5 million tons, and hazardous materials account for 3.5 million tons.

“The Ohio River is part of the corridor to the northeast, and what goes past us on barges has been produced locally and from around the country,” he said. “And, if you think about it, much more chlorine can be transported on a barge than on a truck. Economically, it works out better for the companies to use the river.”

“I’m not sure what rationale Coast Guard officials would use for not allowing fracking waste to be barged on the Ohio River because of what already is. Fracking fluid, when it comes down to its hazard vulnerability, is going to be low on the list compared to the other things that are barged,” Vargo explained. “What I told the Coast Guard commander was that fracking fluid – while it’s not a hazardous material – should be transported in the same kind of barge that’s used to transport chlorine. Those barges are double-lined and sealed shut and considered very safe.”

The extended debate over the fracking waste has not proven surprising to the EMA director, but Vargo said no matter what decision is rendered, he and local emergency personnel will be prepared. Vargo’s office works with Wheeling’s first-responder departments to develop emergency plans so local authorities are as prepared as possible for the “if” and the “when.”

“If a chlorine leak takes place on the river, our reaction would depend on wind currents,” he said. “A chlorine leak on one of our highways, interstates or on the river is a multi-state response because of our position geographically. We have never responded to a chlorine leak on the river, but if it took place near the Fort Henry Bridge, we would have to shut down Interstate 70, and maybe Interstate 470, too, depending on the direction of the wind.

“If such a leak took place near downtown Wheeling, we may have to evacuate the downtown, East Wheeling, North Wheeling and South Wheeling – depending on the way the wind is blowing,” he said. “It would also depend on what chemical it is and the properties of that chemical.”

While a similar action plan would not be necessary in the case of a barge accident involving fracking waste, the pending decision has attracted much reaction in the Upper Ohio Valley.

“As far as whether or not the fracking fluid will be allowed on the river, the Coast Guard has thousands of public comments to consider, and that means people are paying attention. It’s the culture around here. We are used to what we are used to, but this industry is new to us,” Vargo said. “At the time it became legal to transport things like caustic soda, chlorine, and the gases, there was no debate like there is now over the fracking waste. But I believe that’s just a sign of the times.

“Today, we have a cleaner Ohio River than we’ve had in the past 60 or 70 years. When these materials were added to the approved list, the river was already very polluted, so no one really thought it could get any worse,” he said. “But the environment has rebounded since those days, and there are a lot of people who want to see it stay that way.”