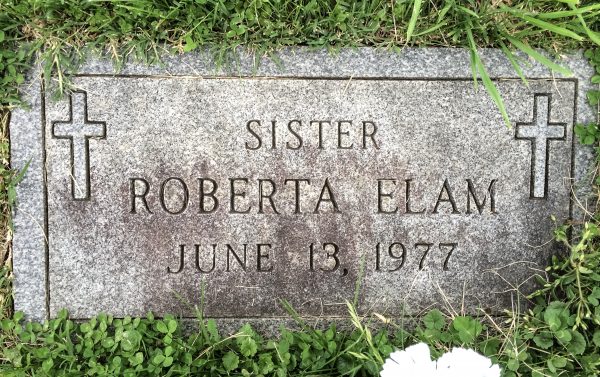

(Editor’s Note: This is the first of a two-part series examining the murder of Roberta Elam in Ohio County on June 13, 1977. The second chapter will be published one week from today.)

Thirty-nine years, two months, and one week ago the unfathomable took place on what most in the Wheeling area considered hallowed ground. The press reports told a brutal story about how a young lady preparing to become a nun in the Roman Catholic Church was killed in broad daylight on the campus of Mount St. Joseph’s, the home of a community of nuns and also a care center for aging sisters and their families at the time.

Roberta Elam, who lived in the Fulton neighborhood of Wheeling before she arrived at Mount St. Joseph’s for an eight-day meditation stay, strolled over to an area of the convent’s campus that offered an overlook of a couple of links of Oglebay’s Speidel Golf Course to contemplate her lifetime commitment. Elam was 26, the oldest of four children and a native of Minnesota, moving to Illinois and New Jersey before making the move to Wheeling in 1976, and was last seen alive in the convent kitchen while grabbing a quick snack before taking her final trek.

The facility’s staff told investigators she visited the kitchen around 10:30 a.m. on June 13, 1977, and traveled to a secluded location near the orchard to meditate about life as a full Roman Catholic nun. Prior to enrolling with the Sisters of St. Joseph in the fall of 1976, Elam, for a little more than a year, was the coordinator of adult religious programs presented by the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston throughout the state of West Virginia.

Known as “Sister Robin,” she was pleasant, according to those who once worked there, and yet Elam was never seen alive again by anyone else but her murderer. The bench on which she likely sat was knocked over; Elam was obviously dragged by her throat away from it; she was raped; and then she was strangled to death and left where she gasped her final breath.

“The next day I had to call up to the infirmary to see what time they needed me to work, and the girl that answered immediately said, ‘Vivian, there was a nun that was murdered and raped here.’ I said, ‘WHAT?!’ And that’s when the phone went dead,” remembered Vivian Elliott, who, at the age of 20 worked at Mount St. Joseph’s as a nurse’s aide. “Immediately I thought someone must have been listening because the connection just died, and I didn’t call back.

“And that’s when I thought about what the girl told me. A nun was murdered and raped? And as soon as I did return to work, the officials were interviewing everyone who worked there and stayed there,” she continued. “I guess the investigators thought that someone had to have seen something since it took place in the middle of the day. But apparently no one did because it’s still unsolved after all of these years.”

According to media reports, Elam’s partially clothed body was discovered by a groundskeeper approximately three hours after the crime had been committed. Her neck and legs were bruised, and her slacks and white blouse were soiled with residue from the ground and from the attacker.

Leads flowed into the Ohio County Sheriff’s Department and to the West Virginia State Police because people thought they saw something along Pogue Run Road. Elliott was among those.

“I can remember everything about that as if it was yesterday, and I remember the night before this occurred there was girl who came into where I was working to relieve me right around 10:30 p.m.,” Elliott explained. “The girl asked me, ‘Do you have someone waiting for you that has a black van?’ I told her no, and that’s all she said then.

“Then my mom came to pick me up at 11 p.m., and I asked her if she saw a black van, and she told me that she hadn’t, and as we left the property I didn’t see any kind of car,” she continued. “I never did hear anything more about a black van. The investigators did talk about a car but nothing about a black van.”

Elliott worked at Mount St. Joseph’s, a facility situated on the former Holloway Estate adjacent to land owned by Oglebay Park, to gain entry-level access to the region’s healthcare industry because her goal was to find employment at a local hospital. The duties involved helping the sisters with their aches and pains and to assist the nurses and physicians employed in the convent’s infirmary.

When it was her turn to speak with investigators, she did so one-on-one in an office with only a desk and a couple of chairs in it on the first floor of the building that housed the medical care area at the time. And she did recall seeing something at that time.

“There were areas at the time along Pogue Run Road where cars could pull off of the road, and that’s also where a lot of the lovers were parking so they could make out there,” Elliott said. “And there was a car in one of those areas that I remembered seeing. It was blue, and I think it was a Chevrolet, but I’ve never been sure of what model it was. I knew that it wasn’t a new one.

“I remembered seeing the same car a couple of times, and I told the officials that when I was interviewed,” she said. “I wasn’t really sure if I had met Sister Robin, but when I did return to work, some of the nuns told me that I did meet her. I know that I had seen her but not that we had met.”

Also at one time deputies and troopers examined what similarities, if any, existed between Elam’s murder and a series of rapes and murders that haunted nearby Washington County, Pa. Nothing has ever panned out despite the involvement of various law enforcement agencies, but it left the public to wonder whether or not a serial killer was loose. The West Virginia State Police are in charge of the cold case today because of mandated jurisdiction, but four decades ago they were joined by the sheriff’s office and the Federal Bureau of Investigation, too.

“Everyone involved with the investigation was pretty frustrated at this point because everyone believed it should have been an open-and-shut case,” said retired FBI agent Tom Burgoyne. “It was a shocking situation to everyone and not just for the investigators on the case. No one in the community could believe someone would do such a thing to a nun let alone believe that it could take place where it did. I remember being very surprised when I first heard about the murder because of who it involved and where it happened. I was shocked, really.

“But you also have to remember that back in 1977 Oglebay wasn’t how it is today. There was the golf course but not much else in that area,” the former special agent said. “The nuns went there because it was quiet. They could think there, and that meant no one was around. So when this murder took place, there really wasn’t the chance for anyone to see or hear what was going on.”

A Frightened County Locked Down

It seemed off limits to a parochial school kid who knew it was never a good idea to anger a nun, especially one with a ruler in her hand, but you knew they were up there, and you left it at that out of respect and a little bit out of fear.

Mount St. Joseph is the same sanctuary today that it has been since the estate was transformed into a home for the sisters during the late 1950s. Bishop Richard Vincent Whelan, the very first bishop in Wheeling, requested sisters to work with the development of the new diocese in 1853, and four nuns arrived soon to work in a new hospital. After two more sisters joined the group the six formed the Sisters of St. Joseph and, in May 1860, the sisters were established as an independent Congregation by Bishop Whelan, according to the organization’s website.

The population of nuns in 1977 in the Wheeling area numbered many more than the sisters do today in the entire Upper Ohio Valley, but Mount St. Joseph continues operations with 32 nuns currently in residence and approximately 51 still serving in the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston. The infirmary still offers care, and a strong Auxiliary organization works to raise funds for the sisters.

Despite the addition of several cabins and a second professional golf course on nearby Oglebay land, the property remains a tranquil place today, but the loss of Sister Robin has become something of a legend of the land. People with roots in Ohio County and who are between the ages of 60-80 years old lived it; those between 30-59 years old may have heard about it; those younger likely noticed the deadly tale during recent cold-case coverage.

“Everyone in the whole area was shocked and everyone was living in fear for a while,” Elliott recalled. “She was very young, and she was studying to become a nun, and I don’t think anyone could imagine something of this magnitude ever happening on that property. Who knew who was out there waiting for another one?

“The nuns no longer ventured out, and the nuns would go to the pool and swim, and that stopped, too,” she continued. “After the first few days no one wanted to talk about it anymore. And the nuns that operated the place never came to us to tell us to be careful going outside. I think they wanted to try to forget it, but no one really could.”

Doors were locked, and windows were secured despite a summer season during which the mercury reached as high as 87 degrees and the fact the majority of homes in Ohio County relied on fans instead of central air-conditioning. People were scared. What line would this animal not cross if he would rape a nun on convent grounds in broad daylight and then strangle her to death?

Bill Hanna, a retired associate professor of English and journalism at West Liberty University, has lived with his family for the past 44 years in a small neighborhood situated in very close proximity to Mount St. Joseph’s. He recalled his reaction about living less about a mile from the crime scene.

“All of a sudden we had to lock our doors. We had to look up and down the street to see if there was anyone new that we didn’t know. No one seemed to know anything, so we didn’t know what to think,” he said. “It was simply unbelievable to everyone, not just here where we live, but everywhere I went. Those things didn’t happen around here; they happened in bigger cities far away from us.

“A state trooper came to our house and knocked on the door. He was a pretty big guy, I remember,” he said. “He asked us if we had seen anyone run out of the woods, run across the street, and down through the woods toward G.C.&P. Road. He said that they thought that could have been how he got away from the scene. But we hadn’t seen anything.”

Hanna and his wife, Jane, had two children at the time, David and Stephanie, and they followed the press coverage on a daily basis.

“We were in stunned disbelief to think that such a thing took place in our own backyard,” he said. “A nun? I personally never thought that was possible.

“The story was all over the place, and it was Page 1 every day because, I think the editors were in disbelief, too,” Hanna continued. “We had police walking all over our neighborhood for more than a week, but then it just felt as if whoever had done it was going to get away with it.”

Before deciding to retreat to Mount St. Joseph’s, Elam was assigned by the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston to travel to West Virginia’s most rural areas to offer information about available Catholic-based social services. It was a mission involving helping people, and it was, according to the interviews of those in residence at the time, exactly why she was working toward her vocation.

She often took those trips alone or with another sister, and the nuns trekked the campus freely, never fearing harm. But after June 14, 1977, the written and the unspoken rules for those living, working, and visiting Mount St. Joseph’s underwent a drastic change.

“Everything changed for everybody. Everything about how we did things there, and they even got a German Shepherd to guard the property,” Elliott reported. “It was devastating for the entire community. People were talking about all of the details for weeks because they couldn’t believe someone could do such a thing, especially to a nun. That was just unbelievable.

“The place was on total lockdown, and no longer would I go outside to enjoy the quiet and look up at the stars while waiting for my mom to pick me up,” she said. “We knew there was a chance someone could be out there waiting for another opportunity or something like that. None of us wanted to put ourselves in the situation where that could happen again.”

The case file, according to Det. Doug Ernest of the Ohio County Sheriff’s Office, remains off limits to media members simply because it is an active case. Most of what has been collected during the past four decades rests in a few banker boxes, and inside are many details of the crime that only the perpetrator and investigators would know.

“We’ve received several requests for file reviews, but those have been turned down,” Ernest explained. “That tells me there is still a lot of interest in this case, and that’s likely because it’s one of those sensationalized crimes that have never been solved.

“We don’t have a lot of murders around here and definitely not one like this one. And because of some of the sisters who were living there at the time Roberta Elam was raped and murdered, I’m not going to stop,” Ernest added. “I want us to solve it for them.”

Weelunk.com publishes daily, to receive notification of new stories like this one, be sure to like us on Facebook here: Weelunk