(Editor’s Note: This introduction is the first entry of a series of stories that will focus on the history of the game of baseball in the Wheeling area.)

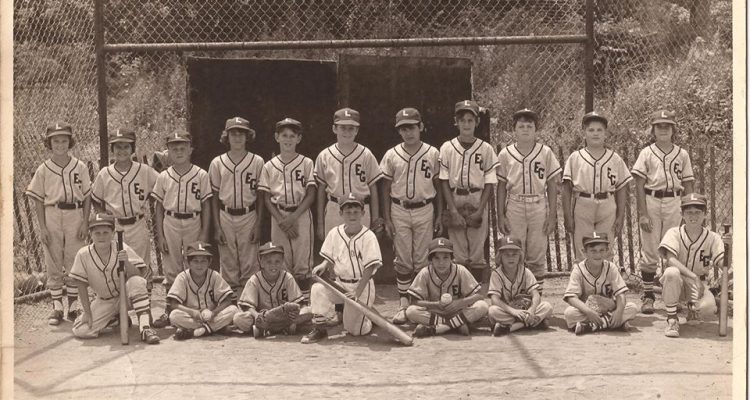

See the kid in the white, wool uniform, in the middle, holding the bats?

That’s me.

Age 5.

I was the bat boy because I was still a year too young to play Mustang ball back in the summer of 1971. That’s when the Mustang Division of Little League Baseball included kids aged 6 to 10. Then there was Bronco for two years, Pony after that for 13-14 years olds, and then the Colt Division, and American Legion Post 1 Baseball entered into the equation once a local, Ohio County ballplayer turned 15.

And that was, of course, four decades ago, and since then youth baseball has added some changes, including new divisions to involve 4-year-old boys and girls, participation trophies, mercy rules, and more in-game, player-with-coach counseling than ever allowed before.

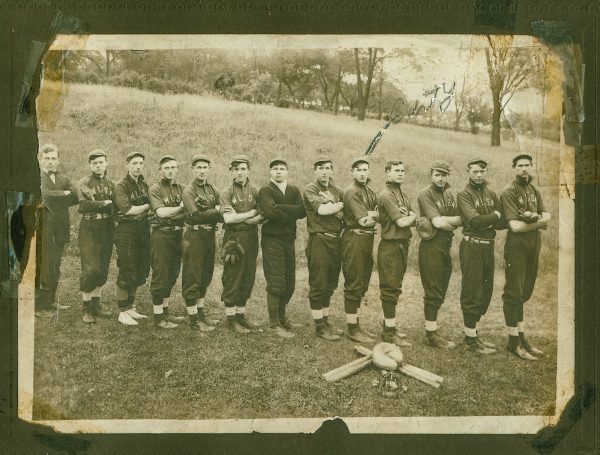

The game of baseball has a storied history in the Wheeling area, dating all the way back to late 1866, when, just three years after West Virginia became the 35th state, the Hunkidori Base Ball Club played the Union Base Ball Club from Washington, Pa., at the Wheeling Island Commons. It was, according to materials archived by the Ohio County Library, the very first baseball game played in the Mountain State.

The Hunkidori club’s roster was comprised of mostly Civil War veterans, and just two years later more than 20 teams had been founded throughout the city of Wheeling and in a number of East Ohio communities. Several clubs represented neighborhoods like East Wheeling, Bellaire, and Wheeling Island, and others were sponsored by local companies. By 1877, the city of Wheeling possessed its very own professional baseball team.

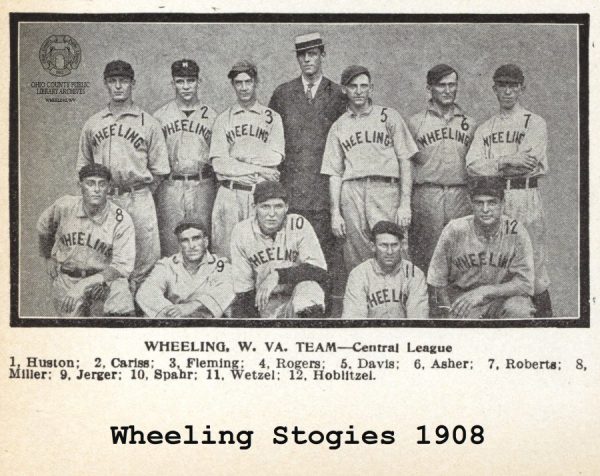

The ballclub had several names under different ownership groups, including the Standard, the Nailers, Mountaineers, and finally the Stogies. The Stogies, according to Baseball-Reference.com, were affiliated with the New York Yankees for two years (1933-34), and that is when Babe Ruth paid a visit to the Friendly City, said local legend Bo McConnaughy.

“Post 1 used to play their games on the field in Fulton that was close to the school. The trucking company is there today, but when I was a kid it was a pretty prominent field,” McConnaughy said. “And that’s where Babe Ruth played when he was touring with the Yankees and they came to Wheeling. He hit a ball to right-center field that traveled into the parking lot of the grade school, and most people had never seen a ball hit like that.

“Home plate used to be near the creek, and you hit toward National Road,” he said. “There used to be stands at that field, but when I reached the age to play Legion ball there weren’t any stands. People just stood along the sides in foul territory. When Ruth was there, though, it was a decent field. But that was before my time, back in the early 1930s. But we always heard the stories about The Babe in Wheeling.”

As a child growing in East Wheeling, McConnaughy was told many more tales about baseball in the Wheeling area that involved big games, huge crowds, and the dream of becoming a professional player as many had through the years.

“Shoot, when I was a kid and it was summer, we started playing in the morning and didn’t stop playing until the streetlights came on. And every single game we played in the middle of the street, or wherever, was the seventh game of the World Series. We weren’t playing for fun. We were playing to win, and we all wanted to be the hero like Bill Mazeroski was in 1960,” McConnaughy said. “Maybe after the game everyone would go have a pop, but during the game we weren’t friends. We were enemies.

“I can remember some knock-down, drag-out fights after a safe call at first base,” he said with a laugh. “And we played wherever we could with as many guys that we could round up from the neighborhood. Every single day, even in the rain sometimes. We didn’t care. We wanted to play ball.”

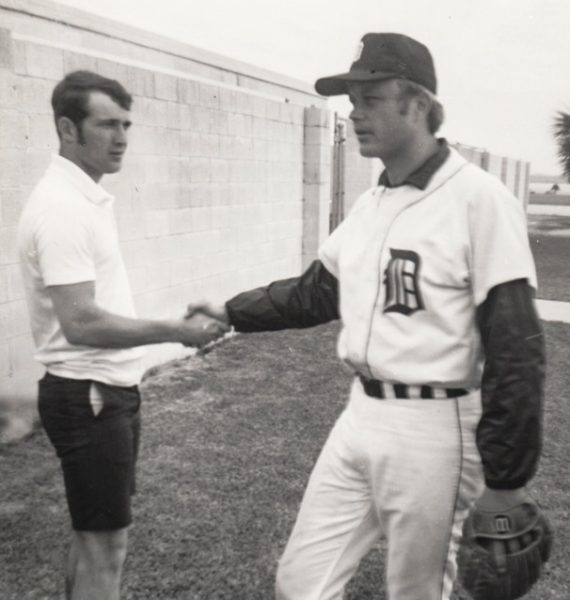

McConnaughy graduated from Central Catholic High School in 1966 as an all-state performer in baseball and then continued his education at West Liberty State College. He arrived two years after the Hilltoppers captured the NAIA World Series championship with a pitcher by the name of Joe Niekro on the roster. Born in Martins Ferry, Niekro was drafted by the Cubs in June 1966 and pitched in the big leagues for 22 seasons for Chicago, Detroit, Atlanta, Houston, the Yankees, and the Twins.

The right-hander passed away in October 2006 at the age of 61.

“A lot of people think both of the Niekro brothers went to West Liberty, but Phil actually went to the pros straight out of high school,” McConnaughy said. “But it was a big deal that Joe was an alum of the program, but he was just one of many great players who played there. I know I had some really great teammates when I was there before I dropped out to sign with the Orioles in 1970.

“No, we didn’t win the World Series,” he said, “but we were good and won the conference before I left.”

Before his departure, McConnaughy was named first-team All-WVIAC as a shortstop, and he spent four seasons in the Baltimore organization before receiving his release.

“I was in Miami in my third year with the Orioles, and we were playing the Mets in Pompano Beach, and I was on first base after hitting a single,” he remembered. “The next guy hit a ground ball to third base, so I was going into second to break up the double play, but when I slid, my spike got caught, and my ankle twisted, and I ended up with a high-ankle sprain that took forever to heal. I would have been better off with a broken ankle.

“One of my biggest assets as a ballplayer was a quick first step. My first move was always very quick, and the coaches loved it,” he said. “But that injury took that away. I had lost that quick step, and I was behind three or four weeks. I played catch-up the whole season and didn’t really start hitting until later in the year.”

It didn’t help that what the team doctor prescribed set him back nearly a month.

“They immediately put me on crutches, and I went to see the team doctor the very next day,” McConnaughy explained. “The doc looked at it and told a nurse to put a heating pack on it, and my ankle swelled up three times the size it already was, and it cost me three weeks of recovery because that doctor thought heat was the best idea. Needless to say, the Orioles fired that guy the very next day.

“But my game wasn’t the same,” he said. “Not as infielder and not at the plate. At one point my batting average was all the way down to .208, and that was the worst I had ever hit during a season on any level. It was a very frustrating year, and even though I had a pretty good season the next year, it was over because I’d lost that first step.”

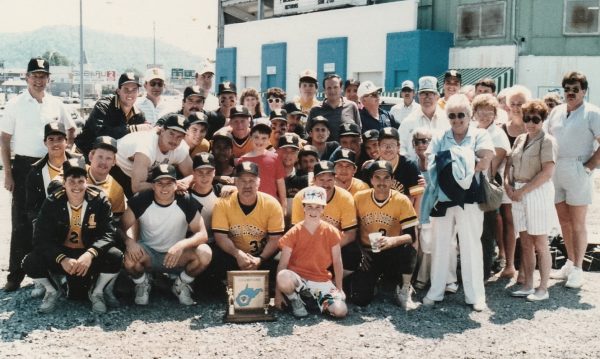

Following his professional days McConnaughy returned to Wheeling, gained employment, and restarted his career with the Warwood Reds.

“I loved playing, and that’s where I could play, and there was always good competition in that league during those days,” he remembered. “Plus, we had a group of guys on that team that were dedicated, and they were there every single game. And we were good.

“But that’s the way it was back then. Baseball in the Wheeling area was something a lot of people took seriously, and we played until we couldn’t anymore,” McConnaughy said. “If you were asked to play for Post 1, it was an honor. It was huge, and there wasn’t anything better than that. As a kid, you followed Post 1 and adult leagues, and you dreamed of playing for those teams, and we played into September. These days the Little League are done playing by July, but that’s not how it was back then.”

He also returned to West Liberty and accepted an assistant-coaching position in 1980 with the ladies basketball team. Two years later he was the head coach for women’s hoops and head baseball coach, a position he would keep until retiring after the 2012 season.

“At one point about five of the players decided to go to the athletic director to tell him that I was too old to coach and that the game had passed me by,” McConnaughy said. “But that was only because those players didn’t appreciate the way I believed they needed to be coached. This game takes repetition in practice, but those guys just wanted to show up, hit, take some ground balls, and then leave.

“So, after 30 years as the head coach, I decided the time had arrived for me to retire. There were other reasons, too, but that weighed on my mind. I knew the game hadn’t passed me by and that it was those players who had the wrong approach to it on the college level, but it was certainly something that I didn’t want to encounter ever again in that position.”

But he’s returned to the dugout as the skipper for Central Catholic’s baseball team, taking the helm following the unfortunate passing of James Conlin in October 2016 at the age of 49. McConnaughy once again will serve as co-director of the Edgar Martin Beast of the East Baseball Classic, a 28-year-old tournament that attracts thousands of visitors to all parts of the Upper Ohio Valley.

These days, though, this soon-to-be 69-year-old sees himself as a man who lived his life wedged in the middle of two very different eras of the game of baseball.

“I’m not sure when exactly it happened, but I did notice that, other than the Legion team, the kids in the Little Leagues weren’t playing the game as much as what we did. Even on the adult level, there weren’t the numbers of guys because of the loss of jobs and population, I guess,” McConnaughy said. “Plus, the economy changed, and both parents had to start working, and that took away the time if you still wanted to raise a family.

“We all had jobs back when I was playing for the Reds, but we were at the field at 6 p.m. to play that game, and if we had the kids, we would take them to the games, and they knew how to behave,” he said. “It’s a different time now; we all know that, but baseball in Wheeling was really something when I was growing up. It was a big deal; it was about winning and having the bragging rights over another team or an entire neighborhood; it was baseball in its purest form, and I consider myself very lucky to have grown up in Wheeling when I did.”

(Photos provided by Bo McConnaughy)