The Beezer Brothers—Pittsburgh’s Twin Architects—Revisit one of their Legacy Projects and Find a Brewery Instead of a Church

Architects Louis Beezer, and his twin brother Michael died more than 8 decades ago, but on a sunny June early morning in 2016, their spirit forms stood side-by-side in silent observation from the old closed balcony of one of the grand structures their firm designed—St. John the Baptist Catholic Church in the Lawrenceville neighborhood of Pittsburgh.

“I still can’t get used to it and I don’t know whether to laugh or cry,” Michael whispered to Louis as they gazed down upon the altered interior of what was one of their crowning Pittsburgh achievements and the early morning light streamed in from the magnificent multi-colored glass of the gigantic round Rose window behind them.

“At least it is still standing,” reasoned Louis. “That’s more than we can say about so many of our other buildings.”

“But a brewery and restaurant?” Michael answered. “Nothing was further from my mind when we worked with the Diocese and old Bishop Phelan on this church. Now, they call it the Church Brew Works.”

“You shouldn’t let it bother you because John Comès did most of the design work anyway,” Louis said recalling the service of another once-famous but now largely forgotten Pittsburgh architect who worked as a designer for the brothers’ firm in 1902. “I wonder why we never see him around on our little visits.”

“My guess is he didn’t ask for that favor,” Michael said.

When the devout Catholic brothers from Altoona, PA were young and deeply immersed in working with Catholic Dioceses in Pennsylvania, Washington State, California, and even Alaska, they had agreed that when they both died, they would ask a favor of the afterlife—to visit some of their favorite buildings once a year on the date the corner stone for each building was laid. Louis passed in 1929 and Michael followed in 1933. From 1933 onward, their spirits made the rounds. Every year, there were fewer buildings to visit.

They had a particular affection for St. John. As with most of their projects, the Beezers poured a lot of attention into the new church. Even as their colleague John Comès tackled the basic design work, the Beezer Brothers supervised the building site, and acted as construction managers as they did on most of their major projects.

The cornerstone of St. John the Baptist was laid on a hot June 1, 1902 on Pittsburgh’s Liberty Avenue in Lawrenceville. A good-sized crowd was on hand and it was dotted with lacy white parasols held aloft as barriers to the sun by women wearing white gloves, flowing skirts, and gigantic floral hats. The men wore stiff winged shirt collars, black ties and black suits.

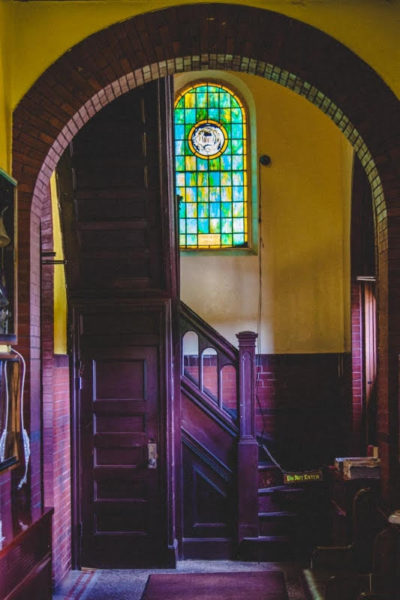

And so, in accordance with their wish, Michael and Louis returned every June 1 to the Northern Italian style architecture of St. John the Baptist Church. They watched quietly from the old balcony where the church’s massive pipe organ was played for 90 years’ worth of weddings, funerals, christenings, Christmas Eves, and daily masses.

Much remained of the splendor of the old St. John during their 2016 visit, just as much had changed.

The magnificent stained glass windows depicting religious scenes still glowed with vivid color in the daylight. The names of the Pittsburgh families who donated funds more than 100 years ago to finance the installations still stand out proudly because they were incorporated into the colorful designs.

Heavy, stone columns that featured decorative carved tops still held up detailed brick archways and stood majestically on opposing sides of the great sanctuary. Their scrubbed surfaces seemed brighter than ever to the brothers.

The eight original gold-painted lanterns that hung proudly below the brick arches from great chains continued to illuminate the details of the hand-painted cypress beams on the high vaulted ceiling—just as the architects directed in their drawings more than 100 years ago.

The rows of polished oak pews, however, had been significantly altered. Now, they no longer sat facing forward to accommodate a congregation. They had been cut from their original 24-foot lengths to 54-inch lengths to form mini pews and then arranged to sit on two sides of big wooden tabletops forming rows of restaurant booths.

The planks that were salvaged from shortening of the pews were used to build a long bar on one side of the old sanctuary.

The original Douglas Fir floors, which, for the last 50 years of the building’s life as a church had been covered with plywood, glowed with a reddish orange hue from an extensive restoration.

One of the old confessionals was completely gone and replaced with an entryway into what the brothers came to understand was now a kitchen. A second confessional sat behind the new bar on the left side of sanctuary and held Church Brew Works merchandise for sale like tee-shirts and baseball hats. That was a change that made both brothers scratch their heads in contemplation when they first saw it in 1996.

Big hulking silver vats now stood along a sidewall behind the bar that presumably held the wide variety of beers. Another set of copper vats, tubes and other brewing mechanisms sat behind a glass wall at the far end of the sanctuary where priests once said mass and delivered homilies, altar boys hustled to do their solemn duties, and countless couples took vows of marriage.

“I have to admit that it has been a spectacular conversion,” Louis confessed to his brother every time they visited since 1996.

“I was somewhat dismayed at first,” Michael admitted. “But this is better than the wrecking ball.”

During their 83 annual visits, the Beezers observed changes to the neighborhood, the city, and to the people as well as to their beloved old church.

During the Great Depression, they witnessed parishioners working together under the guidance of the priests and nuns of St. John collect and then distribute food to needy members of the Lawrenceville community.

In March 1936, the rivers of Pittsburgh overflowed their banks in the largest flood anyone had ever seen, causing widespread damage and homelessness throughout the city and the neighborhood of St. John. The Beezers, during their visit three months after the flood, saw the people of St. John open their church to accommodate flood victims who still had to sleep on the polished oak pews because they had no place else to go.

In the 1940s, they heard the prayers of hundreds of families who sent their young men off to war and watched the church mourn the men who didn’t come home.

And finally, they watched the fortunes and population of the neighborhood decline. It was the late 1950s when the industrial growth that brought steel plants and other manufacturers to the Lawrenceville neighborhood began a reversal of fortune. The mills gradually began to close and jobs began to disappear. Families moved away and the congregation of St. John dwindled.

In the 1970s, the Beezers watched the parish close its school. By 1993, the Diocese of Pittsburgh was forced to reorganize, closing and combining parishes. On their June 1, 1993 visit, the Beezers found their beloved church building deserted with boards over the windows and locks on the doors. That year, they gazed out over the abandoned sanctuary and asked themselves if this visit would be their last.

There wasn’t much for them to see on their visits of 1994 and 1995, but when they returned in 1996, the transformation from church to brew works and restaurant was complete.

The Beezer brothers had left Pittsburgh in 1907, setting up shop in Seattle with a branch office in San Francisco. They thrived as they continued designing homes, banks, and office buildings. But, they never strayed from their main work of designing churches, rectories and convents for their beloved Roman Catholic Church—and they would never stray far from them even in death.