I don’t know a lot about horses. What little familiarity I have is mostly from betting them. I worked at Wheeling Downs when it was a half-mile horse track back when I was in school, but that comes later.

Back in the 1930s, when I was a pre-teen, I got to go to a summer camp called Camp Gauley, and we rode horses and ponies every day, mostly bareback playing cowboys and Indians running through the woods and jumping small creeks. It was wild and carefree and really exhilarating. The highlight memory of that experience was on the Fourth of July, when we wound down in single-file on a sort-of road (more like a trail) to the highway just outside of town to enter the big parade. No one had thought about the fact that these animals had never been exposed much to motor vehicles, and they became a little jittery when they saw the highway traffic. When the float came into view with the brass band on it, they started to dance a bit, but when that band struck up, those poor animals were really spooked. They thrashed and bucked, and kids were flying up and around like corn being popped. George Whitaker was a counselor from Wheeling and was afoot; when he yelled at me to jump, I did, and I was catapulted by the horse bucking. I sailed through the air, and George caught me. We didn’t ride in the parade that day.

Camp Gauley was like a Tom Sawyer style of boyhood. We swam in the river every morning in a pool made by a dam of rocks that we maintained. This was our daily bath. We gigged frogs at night with a flashlight out of a johnboat, and the cook served them in the dining hall. I will never forget the river covered with rhododendron petals moving slowly down the pool to the dam. We all used the “KYBO”, a multi-hole outhouse where a cup of lime was dumped in the hole after each use. The acronym stood for “keep your bowels open.”

We lived in cabins with two double bunks in each. We had shutters we could prop open for cross ventilation. The openings had screening nailed over them, and there was a screen door. The ponies figured out how to butt open the screen doors with their noses and get to the goodies that our mothers had sent in the laundry boxes.

The initiation was truly unforgettable. It was held in a big gymnasium constructed entirely of wood except for the big stone fireplace and chimney. We were taken in one at a time to be terrorized. We were screamed at the entire time. I remember two of the events vividly. I was shown a stepladder facing a pile of overturned chairs, and after being blindfolded, I was ordered to climb the ladder and jump onto the upturned chair legs. We were screamed at and threatened until we “jumped” — which turned out to be about three inches to the floor. Because of all the screaming threats, I didn’t notice that the platform at the top of the ladder had been moved and lowered with me on it to three-inch blocks on the floor. The grand finale was the “branding.” We were led to the fireplace where a big fire was roaring away. They turned our backs to the fire, and then four big counselors grabbed my arms and legs, pulled my pants down, and told me I was going to be branded by swinging my bare butt back and placed on a burning log. At the count of three I was placed screaming on the log, which turned out to be a large cake of ice that had been slid in front of the fire. One can imagine the effect that the screams had on the poor devils waiting outside.

My dad loved to go there. When he drove me down or picked me up or when Mom and Dad visited, they would stay overnight with the property owner, Dr. Kessler, in his large cabin. Dr Kessler owned the place, and his son Kent ran the camp. Dad thoroughly enjoyed listening to Dr. Kessler’s stories about the mountain people. I remember one he told me about “Rimfire” Hammrick, the inspiration and the model for the Mountaineer statue in Charleston. It seems that Rimfire drank a little over the national average and was prone to boasting and exaggerating his exploits, which were many. One night after a number of rounds Rimfire clamed he could jump the Gauley River, so they all went to the river and had a few more at which time he faded into an induced slumber. His friends decided to put one over on him, so they loaded him into a boat and crossed the river where they took off his boots, stuck them deep into the muddy bank, and then pitched Rimfire’s slumbering body face down, just out of his boots, into the muddy bank. When the sun woke Rimfire the next morning he looked around at where he had “landed” and swore ‘till the day he died that he had jumped the Gauley River.

But, back to the horses. The most embarrassing event was with a girl during my late teens. It occurred at Powell’s on Peters Run Road, which at that time was way out in the country. I had a date. and in order to impress her with my worldly sophistication I took her to Powell’s where they would “serve” anyone, and I was underage. It had two gas pumps in front on a cinder/dirt elevation from the road. The building was a one-story frame affair with a counter in the front part where you could buy general stuff like candy and tobacco products. A long rectangular room in the back had a few tables and chairs, a jukebox, and a very small dance floor. They sold beer and illegal whiskey. The whole outfit was pretty spartan. We were at a small wooden table against the wall with two chairs. I thought it was a choice table because it was under a window, which was swung open by its side hinges providing us with the night air coming down off the hill. I was making my best Charles Boyer impression, truly suave and very worldly, when a horse stuck its head in the window between us looking for sugar on the table. I mean to tell you that certainly destroyed the mood.

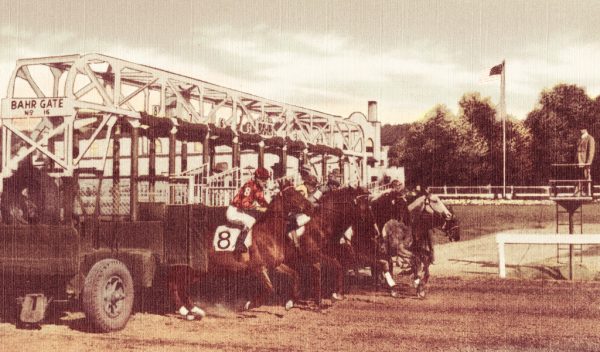

My professional association with horses was in the late 1940s when I worked at Wheeling Downs Race Track. I was on summer break from college, and we all spent many evenings at the Hilltop, a roadhouse owned by Wilson Seibert, who was also a vice president of the track. I asked him for a job at the track, and he told me to report to the track at 8 o’clock Sunday morning. I was there with a big group of men standing under the grandstand when they called out the names of those that were hired. I was among those whose name wasn’t called, and we were told to go home.

A couple of days later I was at the track standing at the grandstand rail when Mr. Seibert came up to me. He was hard to miss as he was a big man and walked with a heavy limp and always had a cigarette dangling from his lip. We exchanged pleasantries, and then he asked me what my job was. I told him I didn’t get hired. He asked if I was at the track on Sunday morning. I said that I had been. He wheeled around and said, “Come with me.” I followed him as he, with a rolling limp, went straight to the sellers’ windows and told one the sellers, “Get Mr. Barr!”

Mr. Barr appeared inside the window, and Mr. Siebert said, “Mr. Barr, this is Mr. Hogan; Mr. Hogan is working for you.” And he turned and hobbled away. Mr. Barr, I found out, ran the pari-mutuel, or betting, end of the track, and he said to me, “Come on in, kid. I don’t know what I am going to do with you, but I’ll find something.”

My first job was as a “runner.” I would run money from the money room to the cashiers should they run out of cash while cashing tickets. I then got promoted to “change boy” which was fast and exciting. The sellers started out each race with a wooden tray of tickets, with a wad of tickets for each horse in a rubber band in a slot in the tray and no cash. I was positioned behind, perhaps, 10 sellers. Before each race I went to the money room and and got change for the sellers. I had wads of five ones folded lengthwise between the fingers of my left hand and and six fives. When the windows opened for each race, the buyers would place their bets. If they bought a two-dollar ticket with a five or 10, the seller would cry out “change,” and I would take the fice or 10 , sometimes a 20 and give back either five ones or a five and five ones or three fives and five ones. It was very fast and hectic for the first few minutes of every race until the sellers got enough cash to make their own change.

It was an exciting time and great pay. On top of the pay, since I ran the whole length of the line going to the money room, I would buy tickets for the cashiers and cash tickets for the sellers. When they won, I was tipped very handsomely for my service.

When a big bet would come in at the bell and a seller believed it was a “boat” race (fixed), he would take the remaining tickets and “go short” against his pay. Often, he would hand me one and say, “Here kid, take your girl out to dinner.” It was a Damon Runyon time with lots of excitement and many stories.

One of our crowd was a tall handsome Irishman named Pat O’Shawnasey. He was selected to work in the owner’s office. After work we all asked what he did “in there,” and he said he just sat at the desk out front and kept the water pitchers filled. One day, he told us after work that one of Bill Lias’ men came out and and asked if he was a college kid and “could he write good.” Pat said yes and that he could. The man reappeared shortly from Lias’ office, handed him a name and an address and told him to write a letter saying “everything is fine” and “make it five pages.” So Pat wrote a letter describing the lovely layout of Wheeling Downs situated on the beautiful Ohio River in five pages. It was a huge success, and Pat’s summer employment became filled with addresses and instructions to write letters saying “every thing is fine” in three pages, eight pages, and so forth.

Wheeling Downs was a beautiful layout, and even though it was a half-mile track, it was considered a jewel in the world of horse racing.