Editor’s note: April is National Poetry Month, inaugurated in 1996 by the Academy of American Poets. After you read about West Virginia’s poet laureate, find ways to celebrate poetry’s vital place in our culture here.

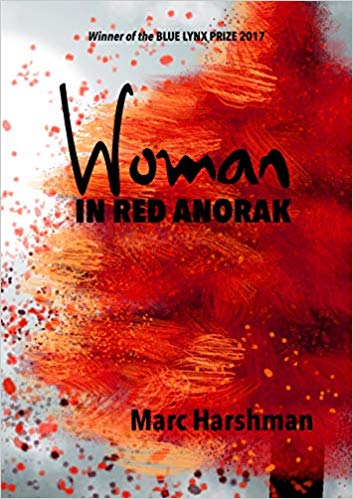

He’s particularly pleased that his latest book came out sooner than expected, and it won the prestigious Blue Lynx Award.

That book, “Woman in Red Anorak,” follows closely on the heels of “Believe What You Can,” which was released in 2016 by West Virginia University Press and won the Weatherford Award from the Appalachian Studies Association.

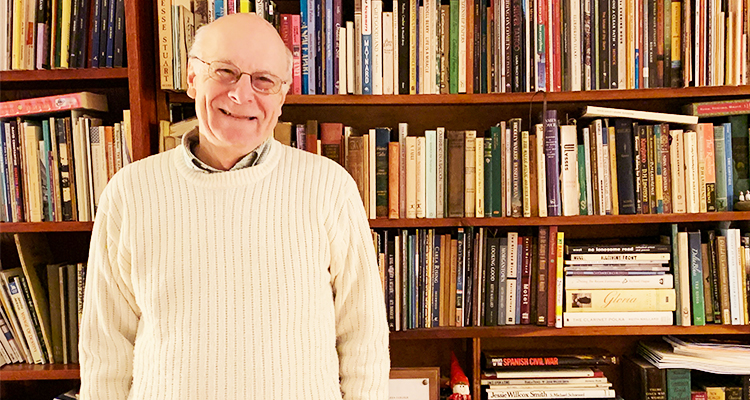

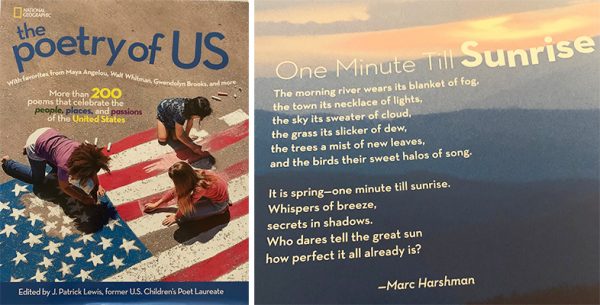

Harshman, West Virginia poet laureate since 2012, has published numerous books of poetry as well as 14 children’s books, many of which have won awards.

BLUE LYNX FOR ‘RED ANORAK’

He was not expecting “Woman in Red Anorak” to make its way to bookstores in 2018. It’s “really usually a long, long time before I get a collection published, and to have this book out after the WVU book came out not even two years ago, [was] completely unexpected,” he said.

He was not expecting “Woman in Red Anorak” to make its way to bookstores in 2018. It’s “really usually a long, long time before I get a collection published, and to have this book out after the WVU book came out not even two years ago, [was] completely unexpected,” he said.

But he had the manuscript ready and submitted it to a few places, one of which was for the Blue Lynx Prize bestowed by the Lynx House Press, a publisher in Spokane, Wash.

“These poems are very new to me; I wasn’t sure I had gotten them in the right order … I’m usually used to waiting for several years, of trying and fiddling and being rejected a dozen times … OK, I need to re-order this, give it a new title, but no … I didn’t have any of that … They just took it,” Harshman said.

He was up against several hundred manuscripts, he noted. “But I got lucky, the right judge on the right day or something like that.”

A DAY IN THE LIFE

It’s tough to peg a “normal” day in the life of a poet laureate, but Harshman describes his “ideal day” and admits, “I don’t get enough of them.”

Morning is spent at the computer completing correspondences. The job of poet laureate takes “a huge amount of time,” … requests for favors, answers, help, blurbs. Also as poet laureate, he’s often commissioned to write poems for specific events, such as West Virginia’s sesquicentennial or Wheeling’s 250th.

“I’ve written a lot of blurbs for poetry books in the last few years and nearly in every instance — they’ve been old friends or poets that I truly respect — I’ve been quite happy to blurb these books. A couple of them have gone on to win awards,” he said.

He also may work on revisions, gathering and sending out poems to journals and magazines, or working on the “business of putting a book together.”

It’s in the afternoons when Harshman puts pen or pencil to paper or fingers to keyboard.

“An ideal day is I’ll have an hour or two free in the afternoon where I’m just sitting at the dining room table or else in the backyard in nice weather, and I’ll have a stack of journals and magazines and books beside me on one hand, and I’ll be reading, and I’ll have my notebook and pencil on the other side and as I read, ideas are always sparking, and the next thing I know, I’m scribbling away. Not that you’d see any connection between what I’ had just read and what I’m writing necessarily, but that’s the process.”

FROM INDIVIDUAL PAGES TO PUBLISHED COLLECTION

A flashback from last summer came to Harshman as he spoke about gathering poems into a collection.

“All the leaves of our dining room table were covered with all these pages … the chairs, top of chest of drawers, everywhere there were … pages of poetry. … That is how I begin shuffling them; they’re not scattered, they are in order. I keep changing them and taking some of away. … I try to feel how they go page to page, so there’s not some jarring change in style or tone. Or, if there is, it’s intentional.

“Let’s say we’ve had two or three prose poems, and they’re a little slower I think — not in a negative way — “so I feel like we need to leaven this a bit, let it have a little air, a little light, and so I’ll put in a more traditional poem. Let’s say I’ve had a real series of serious poems that were dark … I’ll try to breathe some air into that with a little haiku about nature or something like that,” he said.

But first, the poems have to get to the page.

“I’m writing all the time, and, at some point, I think ‘do I have enough to gather … that might make a book, and do I feel like I have a collection that might somehow cohere?’”

Sometimes poems just don’t fit into a certain collection, because of tone or style.

“There are a few poems that are really quite good poems that are not in this volume, and I knew that even before I began gathering, that as much as I like some of these other poems, they somehow wouldn’t fit. Not that they’re better or worse necessarily but just in terms of tone and style,” he explained.

Harshman also wants a certain percentage of poems in a collection to have been published in magazines or journals. “That’s not a necessity, I mean to the world it’s not a necessity, but to me I think it is somehow … [there’s] some kind of validation beyond my own instinctual feelings about the poems,” he said. At least a dozen or so from “Woman in Red Anorak” have been published elsewhere.

EPIGRAPHS, TWISTS AND VOICES

In his latest volume, Harshman utilizes epigraphs to introduce each section of the collection. “They seem to suggest a tone for what may follow.”

He quotes author Neil Gaiman, “There’s no big apocalypse/Just an endless procession of little ones,” at the beginning of the first section in “Woman in Red Anorak.”

“That somehow felt right, that there was a kind apocalyptic sense to these, but not in some huge dystopian vision of the world necessarily; but, in individual situations, individual people, there can be the high drama, life and death drama.” He points to “Shroud,” “which has a woman … she’s falling asleep, taking the dog out to pee, there’s a lovely snowfall, but you begin to realize she’s considering lying down in the snow, and a kind of suicide. … ‘Even now she’s warming to the idea/as she lay herself down/inside all this feathery luxury.’”

Walt Whitman’s quote, “This hour I tell things in confidence/I might not tell everybody, but I will tell you,” opens section two in Harshman’s latest.

“That would be perfect introduction to more personal poems, perhaps, something about my secret life … and it’s not that … for me, here, is that I wanted the reader to imagine a voice, not Marc Harshman necessarily, but the voice in the poems taking you into its confidence,” he explained.

“That would be perfect introduction to more personal poems, perhaps, something about my secret life … and it’s not that … for me, here, is that I wanted the reader to imagine a voice, not Marc Harshman necessarily, but the voice in the poems taking you into its confidence,” he explained.

The voice Harshman hears in many of the poems in the second section of “Woman in Red Anorak” is that of Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer.

“I hear the voice in his poems … inspiring these poems … and informing them to a certain degree,” Harshman said. In fact one poem, “Small Town, W.Va.,” is “after Tomas Tranströmer,” as noted in the book.

“It’s like he … shows little everyday vignettes, little glimpses of life, and you kind of nod your head and go, ‘yes, yes.’ And then there’s these funny little twists, and you suddenly see something you see every day, you see from a completely different angle. There’s almost suddenly a slightly surreal cast to what you’re seeing that hadn’t been expected, and yet doesn’t seem completely foreign.

“It’s not surreal like a surrealist poem, which you’re always kind of struggling to figure how the hell does this fit together, but they seem almost as if it would be natural, and yet you know they’re not.”

An example, “The Teacher,” … “she’s clearly not right, ‘she’s climbed up a tree,’ and yet the imagery, ‘the trees are bare high above except for a few fistfuls of oak leaves persist in waving goodbye’ — there’s that kind of exaggerated metaphor … a little later …’the clouds have stood watching all day.’ So there are little things like that strike me like Tranströmer,” he said.

“In a poem like ‘Relic’ … they found something, which I never define what it is … it’s something small, and I say it’s ‘a small scintilla of truth’ … it doesn’t tell you anything, what is this thing, all you know in the poem is that it’s a thing … the wife has actually pegged it on the clothesline to dry but you still don’t know what it is, and you think, this is all silly … a dragon’s scale, a secret or a bit of history… and at the end, ‘maybe it was a tear, maybe it was that one of hers that he should never have forgotten’.”

“It’s those kind of twists, that if I get it right, I’m really happy. And I feel that with Tranströmer, he always getting that twist right.”

GETTING IT RIGHT

Harshman believes this latest collection is full of poems that are more challenging than others he’s written.

“I don’t mean them to be that way … but it’s the only way to speak true in these poems. … I like to think that they catch you by surprise, a lot of the poems, but in good ways. … You don’t have to have a college education — but I think if you just come at them slowly, you will see something new, that there will be a discovery within the poems, a realignment of your vision, a re-seeing, and I think that’s what I’d want from any poem, that’s what I want from the poems I read by other people. I want to see things in a fresh way and a new way.”

Two of his favorites from the book are “Violets,” the last two lines of which he uses when he signs the book — “a small drop of rain/in each of their throats,” and “Restless,” which is “as good as anything I’ve ever written. I don’t know why or how it all came together,” he said.

“I really feel it’s the best collection I’ve ever written. … Of course, there’s a famous quotation about that by somebody — ‘Each new book is the best book you’ve ever written’ … It’s what you want to say. And I do want to say it; and, in this case, I’m even silly enough to say it’s true.”

• After nearly 38 years as reporter, bureau chief, lifestyles editor and managing editor at The Times Leader, and design editor at The Intelligencer and Wheeling News-Register, Phyllis Sigal has joined Weelunk as managing editor. She lives in Wheeling with her husband Bruce Wheeler. Along with their two children, son-in-law and two grandchildren, food, wine, travel, theater and music are close to their hearts.