Recap: In Part 1, we find my youthful 10-year-old self, 50 years my present-day junior, has been called to the principal’s office without apparent reason or explanation. Worried I had done something wrong I was unaware of — or worse — was being blamed for something I did not do, I sat and listened to a short list of good things I had done during my almost three years at Chamberlayne Elementary School. What was going on? Why in the world was I in the principal’s office?

The principal of Chamberlayne Elementary School paused in his comments to me during our mostly one-sided conversation. He was leaning on the front corner of his desk closely watching me and said, talking to the room far more than to me, “So … Mr. Strong … what … are we … going to do … with you?”He eyed me — I thought he was looking at me as if he were a fisherman, and I was a freshly caught trout. The catch in my throat tasted like a worm-flavored hook. I visualized a thick fishing line between my lips passing over my tongue tickling inside my cheek before turning downward where that hook held fast deep within. I imagined him for a moment wearing one of those fishing hats both of my grandfathers (Hyrum and Fendley) owned. Their fishing hats were covered in fishhooks, lures, and various sizes and colors of hand-made, feathered fly-fishing flies. I envisioned the principal thinking and wondering “now which of my knives do I gut and clean this fish with?”

He was talking again and looking at me; he repeated the phrase “… Mr. Strong … what shall we do with you?” There was that “we” again … My grandmother Nora was fond of saying with a twinkle in her eye and that wonderful voice that always made me feel all cozy, warm and relaxed “We? You got a mouse in your pocket?” Then she would laugh her small laugh that sounded like a combination of the gentle summer wind high up in the trees, the soft cool clear water gurgling in a mountain stream, and the soothing purring and mewing of a 2-week-old litter of kittens. Then she would tickle me and ask, “We? Show me your little mouse friend. Robert, empty your pockets of all your mice.” Then we would both laugh until we were breathless.

He was talking again and looking at me; he repeated the phrase “… Mr. Strong … what shall we do with you?” There was that “we” again … My grandmother Nora was fond of saying with a twinkle in her eye and that wonderful voice that always made me feel all cozy, warm and relaxed “We? You got a mouse in your pocket?” Then she would laugh her small laugh that sounded like a combination of the gentle summer wind high up in the trees, the soft cool clear water gurgling in a mountain stream, and the soothing purring and mewing of a 2-week-old litter of kittens. Then she would tickle me and ask, “We? Show me your little mouse friend. Robert, empty your pockets of all your mice.” Then we would both laugh until we were breathless.

Somehow, I did not think it would be suitable to ask the principal about the possibility of there being a mouse in his pocket, nor did it seem wise to tickle him into revealing the location of his mouse.

In a swift motion, he stood up and walked in a half circle to sit behind his desk, he leaned back in his large padded chair, his fingers interlaced behind his head. While watching me, he crossed his arms, leaned farther back in his chair and made his lips tight while squinting at me. I thought, here it comes. He was winding up like a spring toy. The room grew quiet. He held his breath, I held my breath, the clock in his office had stopped. No, the second hand was moving, but very, very slowly. The silence was broken as he took a deep breath. At the same instant, his two front chair legs hit the floor with a loud double th-thump. He was leaning across his desk intently looking me in the eye.

I felt I had moments to live, a fish out of water, the grill fired up and the proper fillet knife being chosen for the task at hand. I envisioned being disemboweled from stem to stern.

“So tell me, Mr. Strong, you will be leaving us in a few weeks for middle school — have you enjoyed yourself here at Chamberlayne?”

I said softly, “Yes sir.”

“Good, good … your teacher tells me you have taken full advantage of your personal science library area when you finish early with your classwork. Would you like to continue doing science during the summer?”

There it was. He was suggesting summer school. He was holding me back, but why? I just sat there quietly stunned. He waited for me to respond, I did not.

He continued. “Well here it is, here is why I asked you into my office … there is a special regional program that started a couple of years ago in 1966, called the Mathematics and Science Center. The City of Richmond (East-Virginia) and the surrounding five counties of Chesterfield, Goochland, Hanover, Powhatan and here in Henrico have teamed up to create a special six-week-long summer program for high-achieving students in science and mathematics, specifically for sixth-graders going into seventh grade.”

He paused for effect and to let that sink in.

“Each elementary school in this consortium, including Chamberlayne Elementary School, is authorized to send a single student as our school ambassador to the Mathematics and Science Center for this special summer program.”

He leaned in watching my blank face. “We here at Chamberlayne are allotted to send one single student to represent all of us here at Chamberlayne.”

Without taking his eyes from me he slowly leaned back. “The teachers, librarian and I all thought that you (he was pointing at my chest with a powerful index finger) would make a fine science and mathematics ambassador for Chamberlayne Elementary School.”

He picked up the trifold brochure from atop my personal folder and handed me the brochure in a grand gesture. My eyes slowly focused … there was an intricate circular logo containing science equipment and mathematics symbols. Written across the top of the folded page was “Mathematics and Science Center’s Summer Camp Offerings for 1969.”

Stunned, I opened the brochure. Here was a choice of Summer Science Camps by topics and short descriptions. There was Weather, Chemistry, Computers and Ecology. These science camps were eight hours a day, five days a week, for six weeks! There would be a special school bus to pick me up at my house, take me to the camp and would bring me back home at the end of each day. All I had to do was bring a bag lunch each day. I needed to fill out the form and mail it in with a check for $25.

I looked up from the brochure, speechless. I was not being held back. I was being offered a slot in a prestigious summer science camp I did not even know existed 60 seconds ago. The principal was watching me — he was smiling a broad grin.

“Now Mr. Strong, I have already talked to your parents a couple of weeks ago, got their OK for you to attend — they suggested I wait until today to let you know, I agreed. I have already filled out the form for you.”

He pointed to the brochure in my hand. “The school has paid the $25 fee needed with the form, and I sent it to the Mathematics and Science Center along with your test scores and our recommendation letters. All that you have to do is decide over the weekend which of the four topics you want to start with. And, Mr. Strong, you are only allowed to attend one …” He held up his index finger, he softly laughed, “and only one … topic per summer science camp at the Mathematics and Science Center — there will always be future summers for the other topics.”

I nodded and said, “Thank you, sir.”

He stood, pushed his chair back and came around his desk, stood in front of me towering over me and put out his formidable right hand. “Make us at Chamberlayne Elementary School proud, Mr. Strong.”

I slowly stood and shook his hand the way my grandfathers had taught me. “Thank you very much, sir,” I softly said. “Not at all, Mr. Strong. I have kept you from your party long enough,” he winked. “You need to get back to class.”

Party? The principal thinks school time is a party? I guess to voluntarily be the principal of a school with all the hard work there is to do, you need tell yourself you are the host of a nine-month party. I thought not — for the last time — adults are weird. Gently clutching the Mathematics and Science Center trifold brochure to not wrinkle the paper, I left his office and passed by the secretary at her desk. She did not look up.

I scarcely knew what was going on. First I am scared out of my wits by being sent to the principal’s office, and a few minutes go by, and everything could not be any better — I was going to a summer science camp for six weeks!!! Standing outside the entrance of the office building, I glanced across the canopied sidewalk at the entrance to the cafeteria/auditorium building with its all-too-familiar, seemingly random, rectangular mosaic panels of small blue-hued tiles.

Maybe it was my new outlook, or maybe it was the lingering after effects of adrenalin shock. I was seeing the blue-hued mosaic, seemingly haphazard patterned arrays, anew. There were no new recognizable patterns, but there was new meaning in the randomness. Each of the blue-hued tesserae appeared as if taken from the color pallet of Vincent van Gogh while painting his other “Starry Night” masterwork.

Each colored tesserae suddenly resembled a small window looking on to the sky of another world, perhaps another universe. Each mosaic was an array of different windows, a wide array of possible futures vantage points, parallel universes that would never have been before my meeting with the principal just now. Being nominated to attend the Mathematics and Science Center felt big. Big enough that my future — the future — was altered. Not only did I realize that my future had just been altered, I realized that I had the power to choose which possible future I wanted by choosing which class I attended. I had the ability to choose my future from all possible futures. I was no longer a simple floating plankton being carried by the inexorable currents and tides of time and events outside of my venue of choice. I had been given the ability to set my own destiny, set my own course. This was a power I had never felt. I dare say few adults have understood.

The world looked considerably different as I walked down the shrouded sidewalk back to my classroom. The dappled sunlight coming through the pine trees caught my attention, while the bees hummed softly in the clover near the sidewalk. I watched both for a few moments, savoring the feeling of a condemned man on death row being pardoned, acquitted and vindicated. I was a free man, ’er boy, who was about to start a new life — I was going to be the science and math ambassador for Chamberlayne Elementary School attending a summer six-weeks science camp at the Mathematics and Science Center.

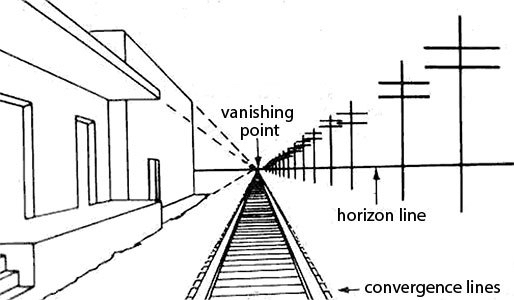

Lost in thought, I turned left to return to my classroom down the long optical illusion vanishing point roofed walkway I had so grown to admire.

Before I reached the library building on the right, I stepped out on the grass and looked up high in the southern sky. There to the left of the sun should be the moon, a two-day old crescent moon, lost in the hazy warm spring sky. The moon was there, even unseen, masked by a hazy sky. I knew it was there, using science — it is all about understanding simple periodic patterns; that is the way the universe works. The use of science is how the Apollo 11 astronauts would make it to the moon’s surface in a few months’ time.

Science, I was slowly understanding, was the systematic looking for, finding and testing of patterns in the physical world. These notions would be reinforced and amplified many fold in the coming seven years where I would be attending summer science camps and fall-winter science camps hosted by the Mathematics and Science Center. I would learn that mathematics is not separate from science but is in fundamental essence, the “language of science.” Mathematics is literally a language of patterns, designed or discovered (lots of debate here) to allow humans to speak “universe” — a universal language about and concerning the rules, laws and patterns found in the physical universe of which we are not separate but an integral part. Life is sometimes said to be the universe’s way of knowing itself. We are perhaps the self-aware reflection of the universe.

Lost in thought, I slowly made my way back to my classroom, while imagining spending six weeks at a summer science camp with other kids my own age having my level of interest. I found my classroom was dark — had they gone to recess while I was gone? I reached for the doorknob, the door flew inwards carrying me with it. As I regained my balance, the lights came on, and familiar kids jumped out of the coat closets yelling in unison, “Surprise! … Happy Birthday.”

I noticed a table with cookies and punch. On the blackboard in large letters and in various colors of chalk was written “Congratulations and Happy Birthday, Robert.”

A close friend came up and said, “Teacher told us after you left about the summer science thing — that’s great.”

It was great — for me the real science and math party started that afternoon on April 18, 1969, and has continued unabated now for half a century.

The next and final part to this essay will outline the events and circumstances in next 25 years that led to the inevitable conclusion that would eventually be the origin of the SMART-Center and it existing now for 25 years.

• Robert E. Strong received a bachelor of arts degree in physics with minors in mathematics and philosophy and has a master’s degree in space studies. Robert taught secondary school math and science in Benin, West Africa, (Peace Corps volunteer) and in American Samoa. He worked as a physicist in a research laboratory. Robert is president of the Near Earth Object Foundation dedicated to educating the general public about Near Earth Objects and providing public StarWatches. Robert and his wife Libby started the SMART-Center in 1994, a hub for science- and math-related activities for area schools, educators and the community. They also operate the SMART Centre Market — an interactive hands-on science store in Wheeling, featuring Orion telescopes, science toys and Kirke’s ice cream.