Their answers were safe answers. No one ever expected that anyone would ever know the answers — unless and until someone actually visited the lunar surface and returned to tell about it. A trip to the moon seemed logically impossible. Most people agreed — we may never know the truths of the Earth’s moon.

Numerous and varied are the phantasmal and whimsical literary notions of getting humans to the surface of the Earth’s moon alive and back again. (A future article topic will be on Ideas of Space Travel.)

Nothing the imagination of writers could conjure before the dawn of the 20th century came close to the actual manner used for the first human moon landing.

The truth of a human voyage to the lunar surface was indeed stranger than the pre-20th century science fiction and fantasy. No one ever imagined a rocket the size and power of a Saturn V, needed for getting three humans and their equipment and supplies, space vehicles and considerable fuel for the journey into Earth’s orbit.

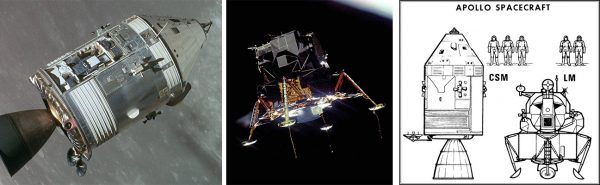

Nor was there ever imagined a Command Module (CM) that would ferry the humans to and from the moon but would never actually land on the moon. The job of landing on the moon was left to a lunar lander (Lunar Excursion Module — LEM) — a vehicle that was designed to never fly in an atmosphere but in only space. A space-flying craft without wings, rudder or any familiar design an Earthly pilot would recognize except rocket exhaust ports, windows, antenna and four wheel-less landing gears.

The Command Module and the Lunar Lander would “fly” joined together crossing the vast gulf of vacuum, cold and radiation that separated the double planets of the Earth-moon system.

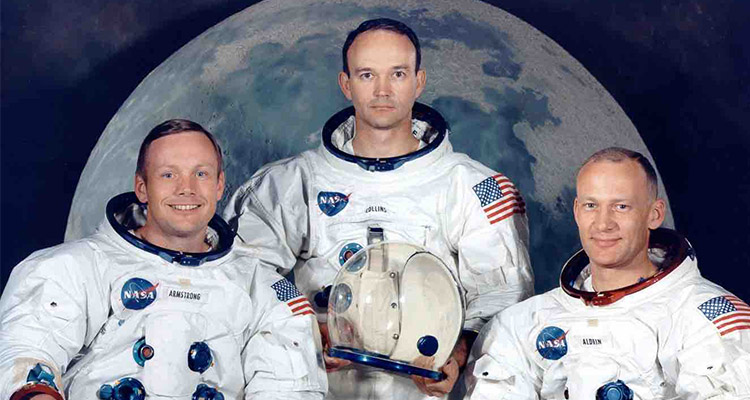

While orbiting the moon, the Command Module would separate from the Lunar Lander with two of the three astronauts (literally meaning “Star-Voyagers”).

The Lunar Lander would leave lunar orbit and gently land (without the assistance of parachutes or wings) onto the airless lunar surface.

The astronauts would exit the Lunar Lander, begin a short (just over two hours) exploration, gathering lunar rocks and soil, and setting up experiments. After returning to the Lander, the astronauts would take a short nap and then return to the orbiting Command Module.

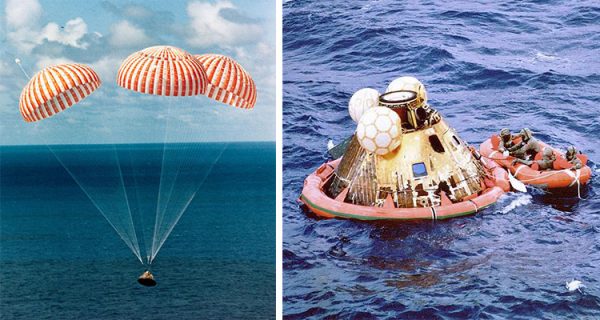

They would then leave the orbit and return to the Earth’s gravitational embrace, and back into the breathable atmosphere to float down into the Pacific Ocean beneath the slow grace of a trifecta of parachutes looking like a triangular collection of red and white circus tents. Straight forward. What could possibly go wrong in the nearly endless daisy-chain of interdependent mission-critical events? Answer “anything.” Privately the astronauts of Apollo 11 put their odds of making it back alive at 50/50.

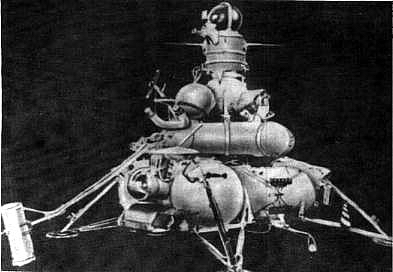

In mid-July of 1969, I was 11 years old, attending the Mathematics and Science Center’s six-week high-octane, hyper-science camp with two dozen other kids as interested in science and math as I was. The class topic theme was “Ecology.” The real topic for me was Apollo 11. A side topic was the Russians launching a spaceship to the moon at the same time. We later found it was named Luna 15. (More on Luna 15 in a future Weelunk article.)

Apollo 11 had launched on July 16, 1969, while I was in the middle of a multi-day science camping trip into the forested mountains of Virginia (East Virginia). I was in science-kid heaven. We spent each day investigating various ecosystems while measuring and gathering data to later analyze back at the M&S Center.

We worked and played hard all day, ate like you can only eat while camping, talked around the campfires until the summer sky darkened and went to our assigned tents for lights out. With dimmed flashlights and hushed voices, we talked late into each night about the pending Apollo 11 moon landing, the Russian moon probe, and Mathematics and Science Center. I was assigned a tent with five other classmates — a heavy canvas WWII or Korean War Army surplus tent that smelled like it was brand new and never saw the wars. One by one, we grew quiet and finally dozed off in science bliss camping exhaustion — each of us knowing he was the last to fall asleep

I woke up in the middle of the night. There was no moon out that night, no flashlights were left on, and it was pitch black in the tent. Amidst sounds of sleeping all around me, there was the soft ticking of a clock above my head. Turning I read the time, 3:15 (I missed pi but would soon see the square root of 10) in the faint scintillating Radium-226 glow of the hands and numbers of a Big Ben wind-up alarm clock belonging to the kid sleeping soundly above my head.

I did not worry about the Alpha particles, Helium nuclei racing away at 5 percent the speed of light from radioactive decaying of Radium-226 nuclei — the glass would easily stop them. It was the Radon-222 produced gas that I should be worried about. I absently held my breath, thought about it, smiled at the darkness of the room and the thought and resumed breathing. The Alpha particles impacting paint containing zinc sulfide crystals were causing numerous tiny momentary little flashes — “radioluminescence.”

These multitudes of flashes appeared as the faint glow of the clock’s hands, numerals and face minute markings. Complete darkness in the tent coupled with being entirely dark-adapted and having young eyes to focus on very close objects let me personally witness the individual luminous interactions of subatomic particles with the zinc sulfide on a scale 15 orders of magnitude (powers of 10) smaller than I was — I loved doing the math. It was relaxing. I had read about being able to see this effect, but slept in a house with bright night lights always on. I stared in wonderment … I was seeing the workings of the physical universe at a scale 15 orders of magnitude (a millionth of a billionth) smaller than myself — I was watching subatomic nuclei interacting with matter.

I wondered, “What object would be 15 orders of magnitude larger than myself?” … “That would be,” I thought doing the powers of 10 in my head, … “10,000 x bigger than the Earth-sun distance … almost a sixth of a lightyear across.” Somehow the Earth to moon voyage of Neil, Buzz and Mike now on their way to the moon gained a newer clearer meaning. The clock hands slowly crept to 3:16 during this pondering. “Square root of 10, a good time to fall back asleep.”

That Sunday, July 20, 1969, back at home, I sleepily watched the CBS Man-On-The-Moon late-night event, sitting nearly against the television tube glass so to not miss anything. At last, just before 11 p.m. my local time, I watched the fuzzy and ghostly wavering images of Neil Armstrong coming down the ladder of the LEM to touch the moon with his boot and heard his first words while walking on another world “… one giant leap for mankind.”

I ran out the front door, screen door slamming, turned right and stood on the dewy grass in my pajamas and bare feet and looked at the yellowing crescent moon and nearby Jupiter nearly setting in my western sky and knew the moon would never be the same. Amber Mars brilliantly shown a quarter the way up the southwest sky. I wondered aloud staring at Mars, “Would that be the next world?”

I heard my parents’ footfalls in the darkness behind me. “Which is the next world?” my dad asked. “Mars” I answered pointing to the bright amber point of light to the left of the moon. My mom asked, “Why can’t we see Neil?” giving me the opportunity to explain to them why that was impossible. We returned to the living room and watched Neil and Buzz bouncing around on the Earth’s moon as we fell asleep.

Little did I realize that I was a part of an estimated 96 percent of American households and 650 million people (some estimates exceed 1 billion) around the world to watch live as Neil Armstrong descended the ladder onto the lunar surface. There were an estimated 3.638 billion people on Earth on July 20, 1969. One out every five or six people on the planet saw the live televised broadcast event. The magnitude of this became clear to me almost 11 years later, at twice my then-current age, the Apollo 11 event I now witnessed would come back to haunt me.

I was teaching science and mathematics in the coastal village of Grand Popo, Benin, West Africa, where I was a Peace Corps volunteer.

In 2016, 7.6 million, or 70 percent of these people in Benin, West Africa, did not have access to electricity. I am reasonably sure the percentage without access to electricity was far higher in July of 1969. Yet on July 20, 1969, (so I was told by people in Grand Popo) a generator, satellite antenna, projector system and projection screen were brought to Grand Popo to allow everyone to watch Neil Armstrong set foot on the Earth’s moon — live. When I was a Peace Corps volunteer in Grand Popo from 1980 to 1982, no one had electricity. The Apollo 11 moon landing was deemed by the local government so important as a one-of-a-kind spectacular feat of our shared humanity that efforts were undertaken to bring this momentous event to the people in one of the poorest countries in the world. I was told thousands arrived (many reportedly walked all night from the surrounding areas) to watch the live televised moon landing of Apollo 11 in Grand Popo.

When I arrived in Grand Popo 11 years later, people were still talking about the Apollo 11 event. My presence in Grand Popo as a U.S. American would frequently bring up the topic. Upon learning my name, people would look at me in astonishment, and they asked for my autograph. If anyone in Grand Popo could afford a camera, they would have asked to have a picture taken with me. I was a rather major celebrity. For you see, as the Grand Popo’ians (I made up that word) understood it, “Neil Arm Strong” was the first human being to walk on the surface of the Earth’s moon. Benin is officially a French-speaking country, and as such, there were subtle French to English to French translational quirks. For most people in Benin, French was their second language. Add to this, few people at that time could read French — they could only understand it by speaking and listening. Given this interesting language background, it should have come as no surprise (and yet it was to me) to find that everyone in Grand Popo thought that I, “Robert Edward Strong,” was none other than the son of the first human to walk on the Lunar surface, “Neil Arm Strong.”

The more I tried to explain to the Grand Popo’ians that I was not the son of the first moon-walker, the more harden was the idea. I would say, “Thank you, but I am not Neil Armstrong’s son.” And they would say laughing, “Only the son of Neil Arm Strong would be so modest” or “We understand how hard it must be for you to never be able to get away from your father’s fans” or “OK, it must be hard for you to forever be in your father’s considerable shadow, we understand.”

Over time, with great reluctance, I slowly accepted the honors constantly bestowed upon me and entered a sort of local pantheon of legendary figures. The people of Grand Popo agreed to preserve my private celebrity status, and in exchange, they would outwardly act as if I were just another resident working in Grand Popo. However, the Grand Popo’ians had no trouble in letting the citizens of nearby villages know that the son of “Neil Arm Strong” lived in Grand Popo. I overheard the following whispered exchange in French “… but please don’t talk to him about his father’s accomplishments, Robert (Neil’s son) is a little shy on the issue and does not want people to make a big deal out of him.”

If any of our gentle readers will be in the Wheeling, West Virginia, area on July 20, 2019, we invite you to join us at the Towngate Theater in Center Wheeling at 1-3:30 p.m. to enjoy a free public viewing of the movie “First Man,” a cinematic story of the life of Neil Armstrong (not my father) and his adventure on the Earth’s moon.

• Robert E. Strong received a bachelor of arts degree in physics with minors in mathematics and philosophy and has a master’s degree in space studies. Robert taught secondary school math and science in Benin, West Africa, (Peace Corps volunteer) and in American Samoa. He worked as a physicist in a research laboratory. Robert is president of the Near Earth Object Foundation dedicated to educating the general public about Near Earth Objects and providing public StarWatches. Robert and his wife Libby started the SMART-Center in 1994, a hub for science- and math-related activities for area schools, educators and the community. They also operate the SMART Centre Market — an interactive hands-on science store in Wheeling, featuring Orion telescopes, science toys and Kirke’s ice cream.