ONE: PEACE CORPS

When we arrived in Cove, Benin, West Africa, starting our assignment as Peace Corps volunteers, we were driven to our village by a Beninois driver, Antoine, in a pickup bâche, a canvas-covered frame on a pickup.

When we entered our place, and a very nice one it was, we were surprised to see a walled-in yard with many fruit trees and two decorative fan palms framing the porch from the entrance gate. We had a house of over 1-foot-thick walls, living room, kitchen with a kerosene refrigerator and three-burner propane stove, which we brought with us, two bedrooms — one in which we set up our bed with the kapok mattress we bought en route. There was a storage room with a short hallway to the back door from the kitchen.

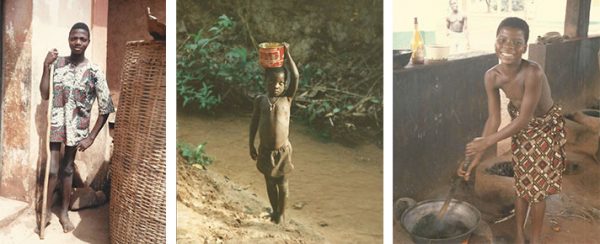

The windows had shutters on side hinges, and the plâfond — or ceiling — made of thick bamboo with about six to eight inches of dirt to insulate the dwelling from the heat generated by the sun hitting the sheets of tin roofing. It was truly an elegant home in a town/village surrounded by “concessions” made up mostly of mud huts with dirt floors and straw roofs in small groups scattered around the outskirts of the village.

The bathroom was a separate little building with a high-level toilette (as opposed to a hole in the floor) — both technically called drop toilette. I remember my first train ride from Cotonou up north on a beautifully made French train. I went to the toilette, and the seat was down, and there were footprints on it. Someone having never seen a regular — high level — toilette had climbed up the seat and squatted on it.

The bathroom was a separate little building with a high-level toilette (as opposed to a hole in the floor) — both technically called drop toilette. I remember my first train ride from Cotonou up north on a beautifully made French train. I went to the toilette, and the seat was down, and there were footprints on it. Someone having never seen a regular — high level — toilette had climbed up the seat and squatted on it.

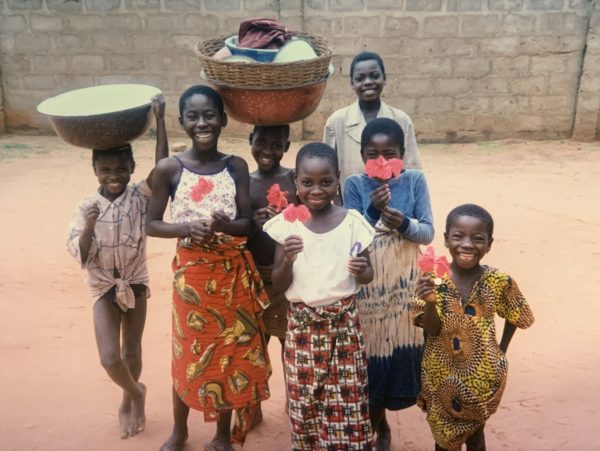

The water for the bathroom shower was in a jarred, a 3-foot to 4-foot-high earthen jar that was fired in a village that specialized in making them. They were fired in an open bonfire in such a way that, when filled with water, they wept through the sides, and the evaporation cooled the water providing a delightful shower as well as drinking water. The jarre was kept filled by the water carriers, women who carried water in large basins on their heads from the well to the customers. The gathering at the well by the women in the morning was the social equivalent of bridge clubs or twigs in the U.S.

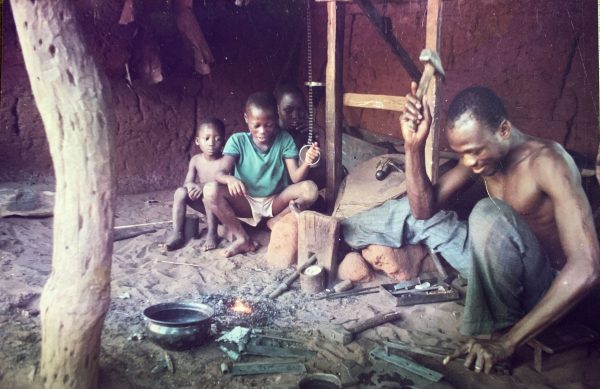

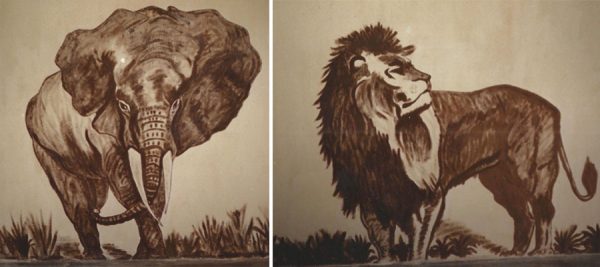

You can imagine our surprised amazement when we entered our bedroom and discovered the walls were decorated with beautiful drawings of African wildlife, elephants, giraffes, etc.! We later found out that one of our propriétaire’s 32 children had done them.

His name is Borgia and is a truly talented artist.

I tried to encourage Borgia in his art and gave him a notebook to use. I found that his only artwork was laboriously done so as not to waste paper. There was no paper in our village (they still used slates in the school) except what was sparsely used by les bureauecrats.

When we returned home for a leave between our second and third year, I brought back large tablets of newsprint and encouraged Borgia to sketch freely by sitting with him in our yard and doing quick sketches of the chickens running around. He was amazing, catching them jumping up and trying to fly. He was not only accurate in his depiction of the birds but caught the flow of the motion.

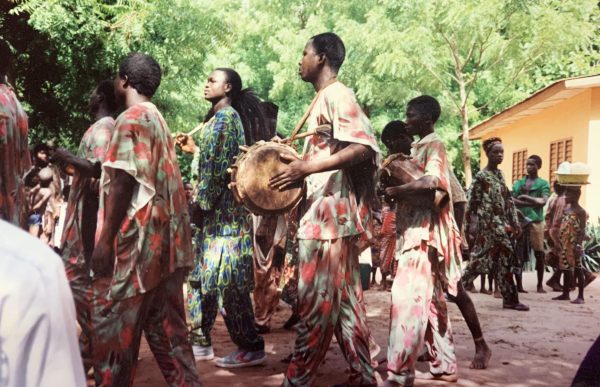

Later during our tour, my wife Susan and I, and Jane Ferguson, a Peace Corps volunteer from a small village a day’s bike ride from us, took a week of vacation and went to Ghana. This country prospered with cocoa production after independence in the 1960s and had made some remarkable progress such as the establishment of a university in the city of Kumasi, capital of the Ashanti region legendary for its gold reserves and its kente cloth, which made the world’s fashion runways at one time.

On arriving in Kamasi, Jane wanted to stay at a Presbyterian guesthouse. Sitting on the second-floor porch outside of our rooms in the cool shade of large trees, Jane told us her father was one of the golden boys, a star football player at Princeton, then a Presbyterian minister who marched with Martin Luther King into the segregated south. Our stay there was silent tribute to her father, who died at a relatively young age of an illness.

Sunday, we attended the service at the Presbyterian church. I tried to stay in the back of the church so I could sneak out if it got too lengthy. We were greeted with warm, loving smiles, ceremoniously ushered up the aisle to three chairs that were placed directly in front of the pulpit and given prayer books (I assume) that I couldn’t read; and so we sat and stood through the singing of the service.

I noticed the leading families were dressed in the traditional tribal attire, sandals with a big gold knob between the big toe and the next. Kente cloth wrapped around them in a precise manner. Very impressive, indeed! We learned that the cloth was woven in silk, and the different patterns designated the various positions who served the king, and the patterns were authorized by him. The ordinary folks were dressed in business suits and lovely dresses. This was undoubtedly a wealthy congregation

The minister mounted the pulpit behind us and proceeded to give a sermon in Twi, the language of the Ashanti people. We sat patiently facing the congregation when suddenly he leaned over and addressed us in fluent American English and asked us if we as white people didn’t try to darken our skin with lotions, as well, so we could present a healthy-looking and attractive tan during the summer months. Startled, we nodded our heads and mumbled our agreement.

After the service, we rushed to greet the “American” Ashanti minister. Of course, his sermon was about humanity always wanting what someone else has. In this case, he was ridiculing those in his congregation who were trying to lighten their skin. We also discovered he had a degree from Ohio State University and had preached in the Macedonia Baptist Church in Wheeling when I was living in an apartment next door!

One of our first stops in Kumasi had been the university where we discovered a well-equipped art department with talented instructors. There were displays of student art that were truly impressive to us. Although the lange franca in Ghana is English, it is generally difficult to understand. The instructors were easily understood, and I discussed Borgia in great detail. They would welcome him as comrade in art with no problem of his being a foreigner.

Before we left the minister and his church, he assured me that if Borgia did attend the university, he would keep an eye on him for his father. People in the West African culture did not commit to this lightly, as he would, as a point of honor, supervise him the same as if he were his son.

When we returned to our home in Benin, I was excited to tell Borgia’s father, Monsieur Djenontan, Andre, who was our landlord, the oversight arrangements we had arranged in Kumasi. Long story short, Msr. Andre was not going to encourage Borgia to pursue a career in art as there was no money in it. Damn!

So we regrouped and put the problem to our friends — Beninois and PCVs (Peace Corps volunteers). A proposed solution was developed. One group of PCVs in the country was on a campaign to build latrines of a special aeration design to replace the morning walk to the fields with the frayed stick in their mouths — brushing their teeth as they provided organic fertilizer to their fields. The problem was, they were not being used; the idea was too foreign to their culture.

Solution to two problems. Hire Borgia to paint designs on the outhouses of his design, making these strange little buildings more culturally attractive and user-friendly. Borgia was making money doing art, and the public hygiene was improved. A gifted lad was earning hard cash and developing his talent and hopefully would be sent to Kumasi, Ghana to study art. The culture of a people was being changed, which would result in healthier communities.

Peace Corps is successful because volunteers live with the people and work with them. After about a year or so, people become used to the étrangers and discuss problems with their friends and wonder what they do in such a situation in their country. Everyone contributes to the solution because the PCV is now a trusted member of the community, not some stranger telling them what to do. They work together, everyone contributes because neighbors trust one another but not foreigners with “how-to” manuals.

A little sidebar: One very important piece of Beninois culture is their tremendous respect for their elders, especially the men. When we first arrived at our post, I was asked by a group made up of locals and another seasoned PCV to attend a formal presentation of a project they wanted to do in this little village.

A little sidebar: One very important piece of Beninois culture is their tremendous respect for their elders, especially the men. When we first arrived at our post, I was asked by a group made up of locals and another seasoned PCV to attend a formal presentation of a project they wanted to do in this little village.

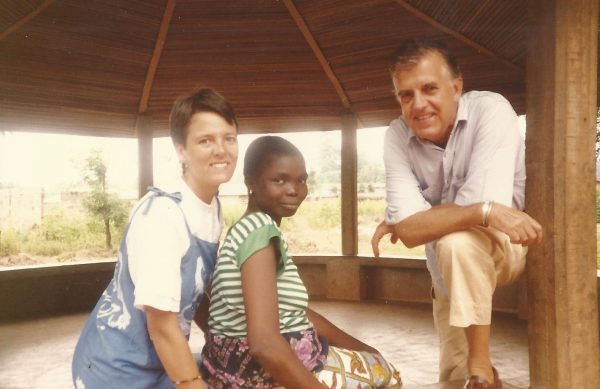

I was 58 at the time, an old man there. We arrived on time and were greeted by the délégué, a holdover from the French system, and the traditional chief. The chief spoke no French, and my three-month crash course with total immersion didn’t make me fluent by a very long shot. Our group was invited to partake of a big spread of food laid out on the ground and a couple of rounds of Sodabee, a strong drink made from double distilled palm wine, in a demonstration of their hospitality.

It was absolutely necessary to eat and drink, as a refusal of their gracious respect would be considered a grave insult. So we ate, and I always made an arrangement with a buddy sitting on the ground next to me to down my drink on the sly after I faked taking a drink on the many toasts. After the formalities that took at least an hour and the goodwill of both parties stimulated by food and drink, we moved into our discussion of the project. The chief and I were seated in chairs, the rest on the ground.

The discussion went on and on, when the chief and I started to glance at one another bored by all the talk we couldn’t understand. He and I were there strictly to lend gravitas to the positions of both parties as “elders.” After a number of glances to size me up, he with a dignity that he wore naturally, stood up and walked over to me and extended his hand for a handshake, which I accepted with a big smile and mumbled a few broken French words of gratitude. And the deal was approved!

Susan really knew what she was doing, spoke passable French and a little Fonbe. I got by on my advanced age.

TWO: BACK HOME

Back home in Wheeling. Kate Marshall bought a house on 14th Street in East Wheeling in 2014 at a tax sale and moved in with her three young children, Gabby and the twins, Noah and Sam. She came to learn to love and become a neighbor of all whom she encountered, and the Wheeling House of Hagar came into being. She has operated successfully according to some vague words of a sort of mission statement, which is not written but always comes out as “love your neighbor as yourself.”

She is somewhat established now as a fixture in the neighborhood after the complaints by a few neighbors sent her to the Planning Committee and Zoning Committee, a number of times to each. She was a hot potato that had been dropped in the lap of city government. She was not a corporation and had no tax-exempt status, so she just didn’t fit neatly into the ordinances governing the city. Politicians all, many new to the game and all wanting to do the right thing for the citizens, finally resolved the dilemma of their consciences, I believe, by coming to the conclusion that it was not good politics (government) to try to satisfy the anger of a few by upsetting, possibly, hundreds of fellow citizens. I believe they should be given credit for making difficult decisions.

One day, a gang of kids came running into the House of Hagar, one of them with a badly cut hand. Kate administered first aid, one of her multitude of skills. When asked how he was cut, they replied they were playing in an abandoned house. She admonished them, saying that it was dangerous.

Their response was as a unit — “What are we supposed to do? Where are we supposed to play?”

It seems they were screamed at when trying to climb the fence at the ballfield; then again climbing onto the roof of a shed at the Elk’s Playground; then again for running down the sidewalk and screaming; then again while kicking a ball they had taped together from junk; and now Kate, whom they had grown to trust, was giving them the devil.

Kate asked them to sit down and come up with an idea of what they would like so they could play. After a while, she was interrupted by the boys who said they wanted a “Fun-Raiser.” She, of course, thought they said fundraiser. After the clarification, they explained they wanted a truck outfitted with balls and other toys and games that would go to different locations for a few hours and allow the kids to play with the stuff. They would make these predetermined stops on a schedule.

And the Fun Mobile came into being. Kate wrote a grant and got a used panel truck. Lots of folks pitched in to buy the truck and the toys. The kids got the old paint off the truck using Kate’s hairdryer. The truck had been a plumbing company panel truck. She told them they would have to run the program and explained how an operating board of directors works. The operation is run by the kids with their “Never Bored Board of Directors.”

It is a rousing success and has expanded operations to other parts of the city. West Virginia University has had faculty and students here to observe.

They were present when the Never Bored Board of Directors made a pitch to a local foundation and won their hearts as well as a grant in the most joyous and effective presentation they have seen in 20 years.

Every once in while I show up and try to encourage kids who are interested to draw. I get their attention by doing quick sketches of them. It does it for me because they think I am really good. One kid went into the complex and brought out a stack of notebooks. He has been drawing really good comic strips for years and never showed them to anyone. The next week his father was out bragging about not only the young artist but his other two, also.

That Friday, on arrival and walking up to the Exley Center, this heavyset little boy with slits for eyes came running out to greet me, stretching out his hand yelling, “Hi, Bill.” I thought Kate had put him up to it. She told me she had noticed he was always by himself and asked him why he wasn’t playing with the other kids. He was ridiculed for being fat. Kate asked him what he would really like to do, and he immediately said a puppeteer. He now puts on shows, has a following and is the cock of the walk. His greeting to me was his own stuff.

THREE: TYING IT TOGETHER

What do these people have in common, that is, the ones working in Africa, and the ones working in East Wheeling? It is not “programs.” It may be that they have discovered a good approach to happiness by not trying to change anyone but themselves, which enables them to love their fellow human beings by being with them and listening with their hearts to the hearts of those who are really only different on the outside.

And aren’t we all different together? An old illiterate sign painter who had the same disease told me years ago, “God never made two people alike and, if he did, one of them wouldn’t be necessary.” A Merton-like statement who said we are not only interrelated but also interdependent.

A Life

Beating this cold iron*

on the anvil of God

seems like futile work.

Until we activate

the bellows of love

and then the hot fire

will reshape the iron.

And the bang-clang

of the hammer

becomes the clear ring

of truth taking shape.

Bill Hogan, August 2019

*The first line “borrowed” from Rumi.