Editor’s note: Today’s post on two gem-like chapels launches a new occasional series on lovely but lesser-known facets of Wheeling’s architectural heritage.

You’ve driven past them. One tiny chapel on National Road — all pale stone, tall spire and a surround of gravestones. And, yet another in the heart of residential Woodsdale — all dark-and-light façade and doors red as holly berries.If, like Weelunk, you’ve ever wanted to peek inside these ribbon-tied-present-like places of worship, this post is for you.

Read on for an inside look at Bishop’s Chapel of Mt. Calvary Cemetery and St. John’s Chapel, two of the most beautiful yet rarely-seen sacred spaces in the city, and a tale of how these chapels came to be.

BISHOP’S CHAPEL: BUILT FOR THE DEAD AND THE LIVING

(Information about and historic images of this chapel were provided by Tim Bishop, spokesman for the Wheeling-Charleston Diocese of the Roman Catholic Church; from historical documents in the charge of Jon-Erik Gilot, diocesan historian; and from Deacon Doug Breiding, who manages Mt. Calvary Cemetery for the diocese.)

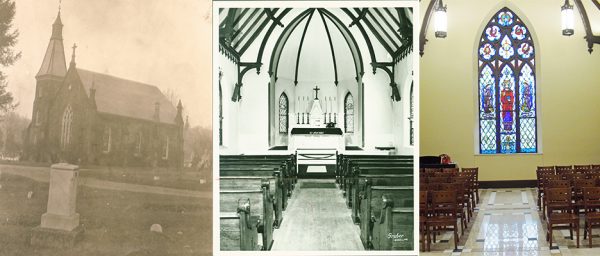

At its heart, Bishop’s Chapel is a 140-year-old crypt, situated in what was once the middle of a final resting place for the Roman Catholics of Wheeling.

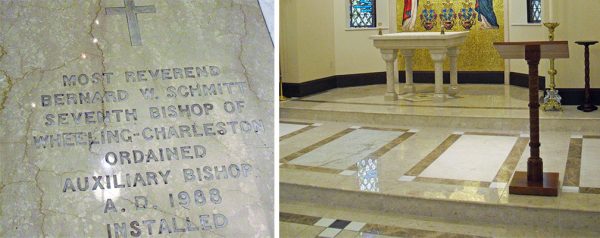

The 1872-founded cemetery has long since crept up the hillside to allow for more generations of burials, but the bishops remain in their chapel. Indeed, the pale marble floor of this 50-seat sanctuary also serves as gravestone for six bishops whose ministry concluded here.

The first five to be buried are remembered in Latin: Richardo Vincento Whelan, 1809-1874; Patritio Donahue, 1849-1922; Joanni Swint, 1879-1962; Thomae McDonnell, 1894-1961; Joseph Hodges, 1911-1985. (Whelan was initially buried elsewhere in the cemetery and moved to the chapel when it opened in 1879.)

The most recent burial — Bernard Schmitt, 1928-2011 — is in English. Counting slabs, there is room for at least another 20.

Death may be literally underfoot, but the space seems to shimmer with life.

The interior walls, ceiling and floor gleam like a gilded cloud. Gothic Revival elements — high ceilings, dark beams and massive, arched windows (stained glass since 1941) — seem to be all that tie it to the earth.

The altar is simply adorned with a cross and a trio of candles. But, at its back, a half-ring of Ikea-modern lights makes another recent touch, a mosaic with a metallic gold field, sparkle like the sun.

“It’s a good gathering spot for the final commitment,” said Breiding. “Especially in inclement weather or for elderly people who cannot handle the uneven terrain (of a graveside service).

Readers who would like to see Bishop’s Chapel for themselves need not wait for a funeral, however. The chapel hosts a Mass 5:30 p.m. on the first Friday of each month.

JOHN’S CHAPEL: BUILT FOR THE CHILDREN

(Information about St. John’s Chapel, part of the St. Matthew’s Parish of the Episcopal Church, was provided by the Rev. Richard Skaggs, associate rector for St. Matthew, and church historical documents.)

When what is now the tightly populated Woodsdale neighborhood was little more than a grand home here and there, St. John’s Chapel was built as a way to bring St. Matthew’s Sunday School programming to children living “out the pike.”

Since its dedication in 1912, the small, cross-shaped building has served in various ways — as a Sunday School, a place for communion on saints’ days and a parish in its own right during the Baby Boom.

Interestingly, it was once a bit of a country club for “churchmen.” In its earliest days, the chapel basement was a lockerroom (including showers) for two tennis courts that were also constructed on the Churchfield grounds.

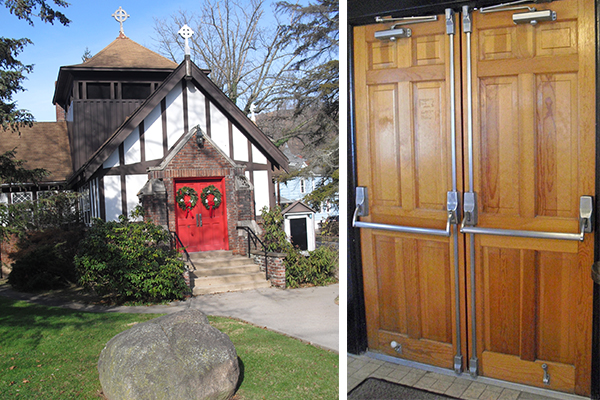

One of modern Woodsdale’s only remaining green spaces, the property was a gift to St. Matthew’s Parish from Mrs. H.C. (Jessie) Franzheim. A granite boulder shipped in from Massachusetts and placed near the chapel’s front doors still carries a plaque bearing her name. The building itself carries another connection: Edward Bates Franzheim, the donor’s son, served as architect.

The building, while much smaller in scale, echoes some of the same Gothic Revival elements of St. Matthew’s. Large, dark-framed windows let in enough natural light to keep the church functional during the day without electric lights. Dark beams support a high ceiling.

“This building’s a lot like an English country church,” Skaggs said of its general appearance and simplicity.

That may be one of the reasons St. John’s makes it to nearly the top of his list of special spiritual places. (At the very top is a hermitage cell used by St. Julian of Norwich, England. Skaggs tracked it down during one of many visits to the Episcopalian church’s home turf. “When I walked into the cell, the spirituality in there drove me to my knees. It was an incredible experience.”)

“I find it (St. John’s) a very sacred place,” Skaggs said in comparison. “I get here about an hour before church starts and take some time to just sit. … There is that kind of holy here — and that’s a good thing.”

At times, it has also been quite busy.

When it was dedicated, St. John’s Chapel took up only one arm of the building’s cross and could be enclosed with folding doors. The Baby Boom led to a full-footprint chapel (and parish designation) and the construction of an education building next door. By the late 1980s, however, population/attendance decline caused St. John’s to return to being a chapel of St. Matthew’s.

Today, St. John’s is open to visitors during weekly services at 5 p.m. Saturdays. The education building is also used for weekly children’s ministry and summer Vacation Bible School.

• A long-time journalist, Nora Edinger also blogs at noraedinger.com and Facebook and writes books. Her Christian chick lit and faith-related non-fiction are available on Amazon. She lives in Wheeling, where she is part of a three-generation, two-species household.