Writer’s note: It’s 2020, and we find ourselves still fighting the same injustices that a prior generation fought more than half a century ago. Why? If we really knew our history, we might understand. But it wasn’t taught. In our textbooks, the historic plight of Black people, from slavery to present — in America, in West Virginia, in Wheeling — was oversimplified, whitewashed or completely ignored. If there is to be the sea change we want and need so that future generations won’t still have to fight those same old injustices, we must face and accept the whole, unpleasant truth. And we must do so, now. The full version of this article originally appeared in the Fall 2019 issue of Goldenseal Magazine. (All Photos provided by Archiving Wheeling)

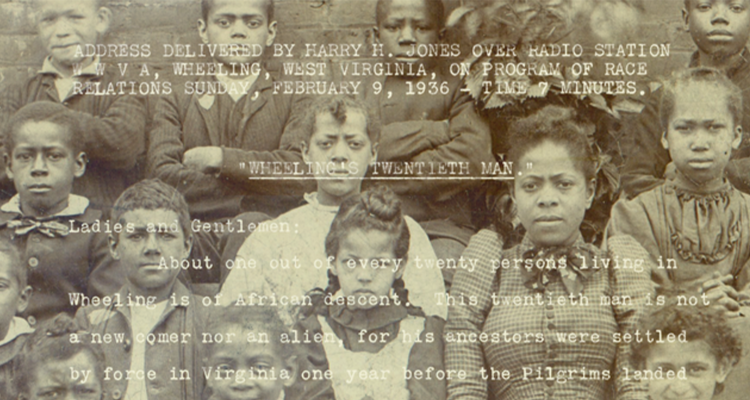

On Feb. 9, 1936, Harry H. Jones, Wheeling’s only practicing African American lawyer at the time, delivered an address over WWVA Radio titled, “Wheeling’s Twentieth Man.”

“About one out of every 20 persons living in Wheeling is of African descent … Justice and candor require attention to the handicaps suffered by Wheeling’s twentieth man… The group, as a whole, has been barred from employment in our local factories, mills, shops, and stores. The group generally has been restricted to personal and domestic service and coal mining… A reading of the ‘job want’ columns of our local papers will verify this complaint of discrimination. Apparently, the test is COLOR of the worker; not his or her training, experience and character…” [Read the full text of the speech]

Jones went on to describe an entirely distinct black community — one with its own doctors, restaurateurs, shopkeepers and even funeral directors. Wheeling in 1936 was actually two cities, side-by-side but completely separate. And black people were not welcome in white Wheeling. This was Wheeling under Jim Crow: separate, but decidedly not equal.

So how did this happen? How did Wheeling, a northern city that hosted the conventions necessary for the northwestern counties of Virginia to break free from the Confederacy during the Civil War, become so starkly racially divided, just like a city of the old South?

To answer, it is necessary to go back to Wheeling’s founding in 1769, when a white Virginian slave owner named Ebenezer Zane made a claim to a narrow strip of land in the Ohio Valley. In 2019, Wheeling marked the 250th anniversary of Zane’s claim with a citywide observation. While discussing plans, Wheeling Mayor Glenn Elliott reminded us to look at Wheeling’s history in a “holistic manner” as Wheeling was a slave city in a slave state.”

Indeed, many of the “first families” who joined the Zanes brought with them enslaved human beings with the legal status of property. Wheeling was part of Virginia, the first slave colony.

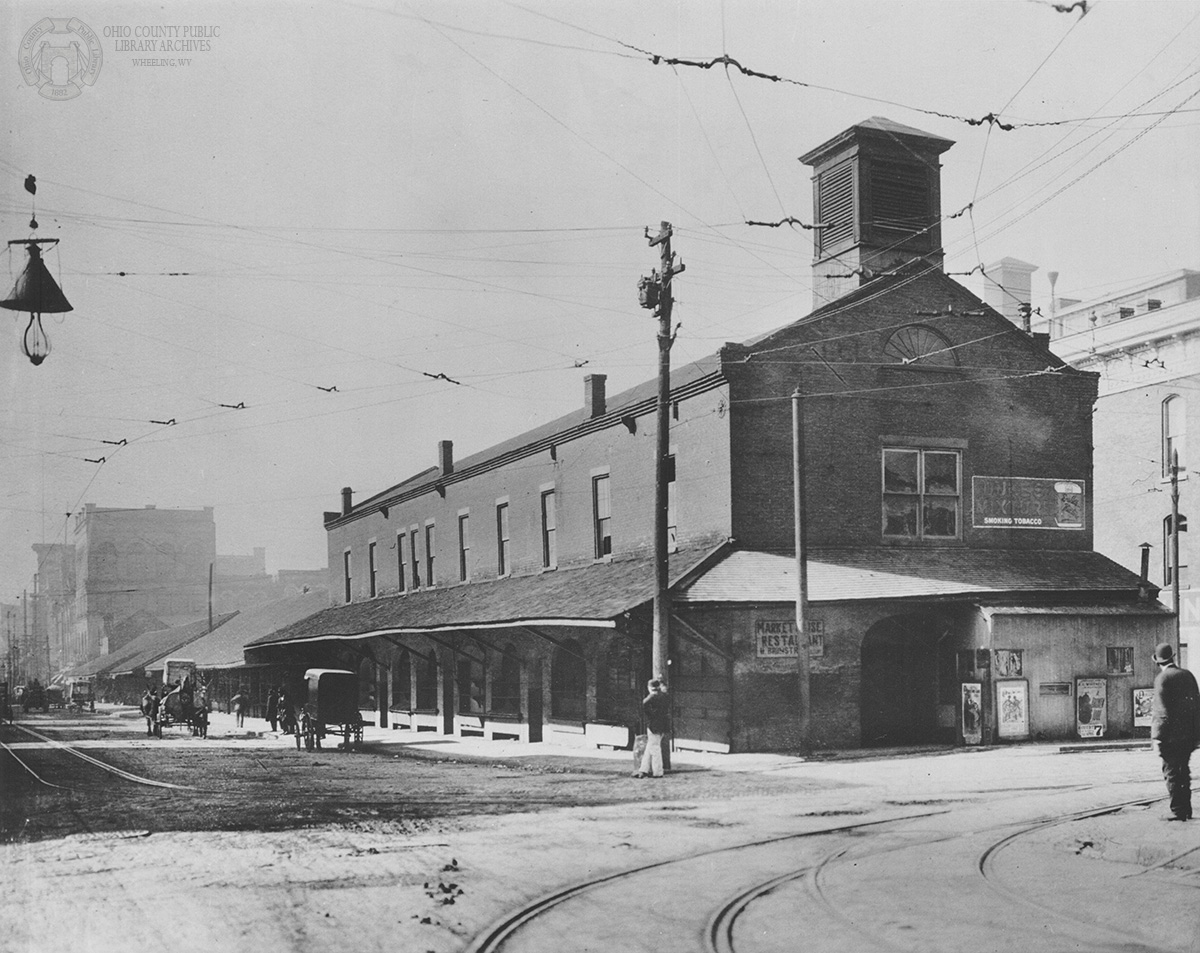

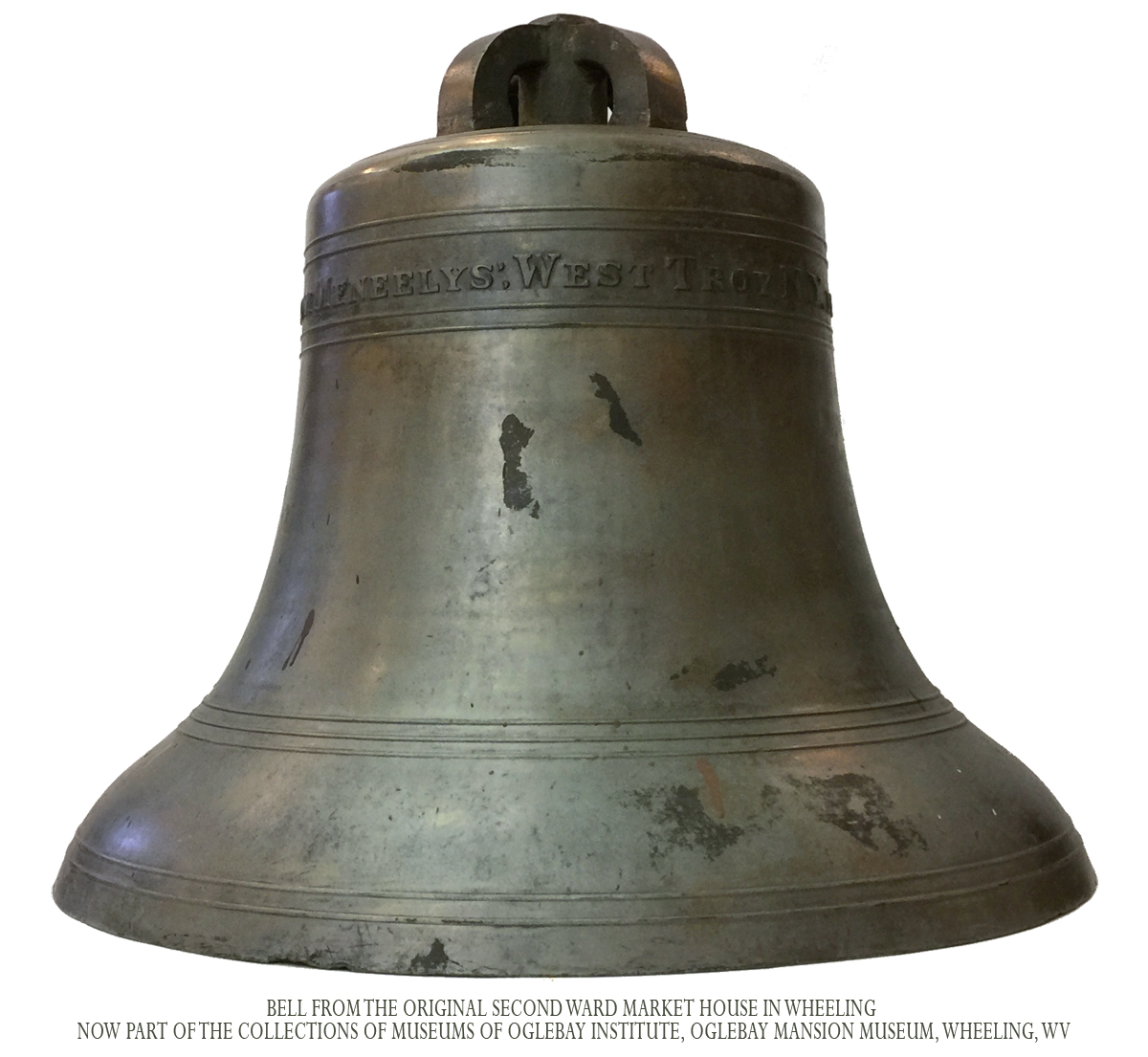

While the number of Wheeling’s slaves remained comparatively small, the city’s position as a transportation hub facilitated a prominent role in the sale of slaves to southern markets from an auction block at the market house on 10th Street.

Moreover, city and county codes often made participation in “slave patrols” a mandatory “civic duty” for white people, even those who did not own slaves. Some scholars argue that the idea of whites “policing” former slaves has influenced modern law enforcement.

By 1860, when Wheeling’s population was 14,100, there were 100 enslaved people in Ohio County. One of those, Sara “Lucy” Bagby, escaped from Wheeling and fled to Cleveland. Her “owner” had her returned to Wheeling under the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, making her one of the last “fugitive slaves” to be returned to her owner prior to the Civil War.

After a series of conventions held in Wheeling, on June 20, 1863, West Virginia broke from Virginia and became the only state to be born of the Civil War. But secession from secession was based on economic concerns rather than abolitionist sentiment.

When Congress and President Lincoln pressured statehood delegates to do something about slavery in return for statehood, a gradual emancipation amendment was ratified, and the new state of West Virginia was born with 18,000 human beings still enslaved within its borders.

Meanwhile, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation only applied to states in rebellion, meaning it specifically did not apply to the new state of West Virginia. Nevertheless, the African American people of Wheeling would mark the occasion for decades after the war ended with elaborate Emancipation Day celebrations.

The Reconstruction Amendments — the 13th, which ended slavery, the 14th, which made ex-slaves U.S. citizens, and the 15th, which extended suffrage to black men — were all ratified in Wheeling at the temporary home for the new state’s government now known at the “First State Capitol.” But a clause in the 13th Amendment was exploited in the southern states to replace slavery with convict labor. Freedmen who fled north to West Virginia to escape this convict lease system and other horrors still could not vote, serve on juries or hold public office.

While the defeated confederate states faced “bayonet rule,” during Reconstruction, federal troops were not sent to West Virginia (a loyal Union state) to enforce black civil rights.

West Virginia’s conservative Democrats leveraged the black vote to re-enfranchise former Confederates. If former black slaves were to vote, the reasoning went, how could white former Confederates be prevented from doing the same? During the 1870 election, Democrats pressured registrars to register ex-Confederates, resulting in a sweeping victory for the Democrats.

Nationally, northern interest in enforcement waned as southern whites re-established “white supremacy,” terrorizing blacks into submission through the use of Jim Crow segregation, the convict lease labor system, the erection of Confederate monuments, the violence of the KKK and lynching.

These tactics existed in West Virginia, even if less virulent. But racism in Wheeling remained systemic, and its practitioners unabashed.

A good example was segregated schools. Drafted by newly empowered Democrats, West Virginia’s 1872 constitution included Article XII, Section 8, which decreed, “White and colored persons shall not be taught in the same school.” This language would remain in the state’s constitution until 1994, and even then, 42 percent of the state’s population voted to keep it.

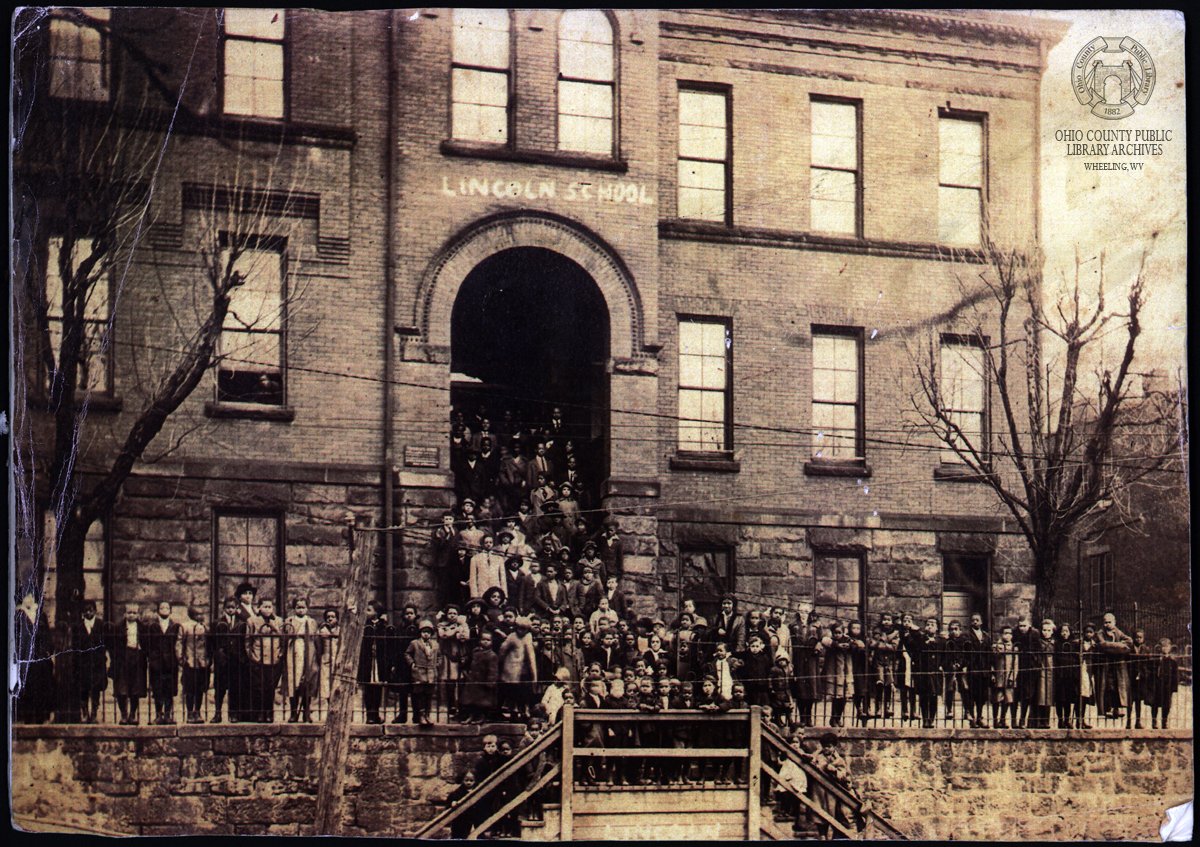

Lincoln, Wheeling’s segregated school, was founded in 1866. The school became a source of pride in the black community but remained underfunded and inadequate. While the 1954 Supreme Court case, Brown vs. Board of Education, ended legal segregation in the schools, the landmark case was by no means the end of “Jim Crow” segregation.

The term emerged from a minstrel song. Minstrel shows, musical comedy plays in which white performers wore blackface to mock African Americans, were quite popular in Wheeling, where fraternal organizations, churches and high schools organized blackface minstrel shows well into the 1970s

When Jim Crow laws were challenged in the late 19th century, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that such laws were constitutional, so long as public facilities were “separate but equal.” Of course, the reality was that separate facilities for African Americans, such as Wheeling’s Lincoln School, remained underfunded and inferior in quality.

For African Americans in Wheeling, Jim Crow meant separate everything — from restaurants and movie theaters to beauty parlors and hotels. Many Wheeling businesses were listed in the Negro Motorist Green Book, a guide for black travelers to hotels, restaurants and other public facilities where they could be served without experiencing the embarrassment of being told they weren’t welcome.

While the black population of West Virginia as a whole dropped significantly just after the Civil War, it grew in Wheeling. With the full effect of the Great Migration (during which some six million African Americans left the old South for opportunity), the state’s black population grew, primarily due to the lure of jobs in the southern coalfields and northern factories. Wheeling’s black population doubled between 1900 and 1930.

Despite segregation, Wheeling’s African American community thrived, producing many entrepreneurs, professionals and cultural leaders. Examples include Leon “Chu” Berry (1908-1941), a legendary saxophone player, and beloved community leader James S. “Doc” White (1901-1988), whose pharmacy became a safe gathering place for generations of African American young people.

As Jim Crow was on the way out in Wheeling and elsewhere, the modern Civil Rights struggle was heating up. But in post Jim Crow Wheeling, African Americans were further disadvantaged by exclusionary zoning regulations and racially restrictive covenants in real estate contracts.

When these policies failed, white people simply left, a phenomenon known as “white flight,” and black neighborhoods were “redlined,” appearing on “residential security” maps to warn white investors away. African Americans also faced blatant discrimination when seeking credit, both for home and business loans.

When these detriments are added together, the terms “white supremacy” and “white privilege” gain context and meaning.

The 1970s also brought “Urban Renewal” to Wheeling. This effort to redevelop “blighted” areas of town (based on redlining) had its greatest impact on traditionally African American neighborhoods, where black-owned businesses and residences were taken through eminent domain and razed.

From major slave market to segregated city, Wheeling maintained a southern attitude toward African Americans for most of its 250-year history. Though it served as the birthplace of a state during the Civil War, after the war, it maintained its custom of treating blacks as second class citizens, separating them from whites, creating a hidden subculture not unlike other northern cities that took an out of sight, out of mind approach to race relations. Shunned and ignored, African Americans created their own separate Wheeling with its own vibrant culture.

This neglectful past has heavily impacted the present. Wheeling continues to struggle to create an integrated, diverse community.

More to come in PART 2. Read the full story of Wheeling’s Twentieth Man: 250 Years of Race Relations in the Northernmost Southern City of the Southernmost Northern State

• Seán Patrick Duffy is the adult programming coordinator at the Ohio County Public Library and the executive director of the Wheeling Academy of Law and Science (WALS) Foundation at the First State Capitol in Wheeling. He earned a bachelor’s degree in history and an MBA from Wheeling Jesuit University and a JD from the Washington College of Law at the American University. He is the author or editor of four books and numerous articles on local history and the editor of the Upper Ohio Valley Historical Review. One of the founders of ArchivingWheeling.org, Duffy is vice president of the West Virginia Independence Hall Foundation Board.