Editor’s note: In an ongoing commitment to discussing race and community, today’s Weelunk post offers the story behind an anti-racism petition drive organized by 2018 Wheeling Park High School grad Hinal Pujara.

No one ever doubted Hinal Pujara academically. She worked her way through an impressive tenure at Wheeling Park High School and into her third year of studies at Ohio State University with encouragement, in fact.

But, Pujara — the American-born daughter of Indian immigrants — said growing up brown in a city that identified as 91 percent solely white on the most recent U.S. Census has created an acute awareness. One person’s American experience may not be the same as even the kid sitting in an adjacent classroom desk.

“Who gets called on? Who is encouraged to excel or challenge themselves?” Pujara asked, noting that being of South Asian descent has worked in her favor more often than it has worked against her.

In June, as the death of George Floyd while in the custody of Minneapolis police expanded interracial support of the Black Lives Matter movement, Pujara brought such questions into the local arena.

She launched a petition drive on social media, asking Ohio County Schools to create a plan to address racism and protect students of color. The petition took off, garnering hundreds of signatures almost immediately and, more surprisingly to her, personal stories of racism.

“I read all the testimonials as they were coming in,” Pujara said. “It was just … jaw dropping for me. A lot of us didn’t know about it because we weren’t in those same classes.”

Ohio County Schools have since launched a multi-pronged response that includes a plan of action inside the school system and collaborations with other organizations outside the school system. (Read an earlier Weelunk story that includes more about this effort.)

“I’m pretty content with what they’ve come up with,” Pujara said. “I’m just hoping that they’re (goals) being regularly evaluated and followed through with.”

A LEARNING CURVE

The realization that her family was different than much of Wheeling — and that that difference would matter — came as soon as Pujara started school. It literally changed her first name.

In Gujrati, her parents’ native language, Hinal Pujara’s first name is pronounced HEE-null. At school, her classmates and teachers spoke it as hih-NAHL. The change stuck to the point that is how Pujara and her family now pronounce it, as well.

“It shaped who I am,” the former co-captain of Park’s illustrious speech and debate team noted. “It’s actually something that I’ve done speech pieces about.”

Other than the Americanization of her name, Pujara said school rolled along in a largely positive way. While her own parents are middle class — her father works in the same position at a local Kroger he took on as a new immigrant in the 1990s and her mother is a physical therapy aide at Wheeling Hospital — she said she was perceived to be part of a “model minority myth” known for top academic and professional achievement.

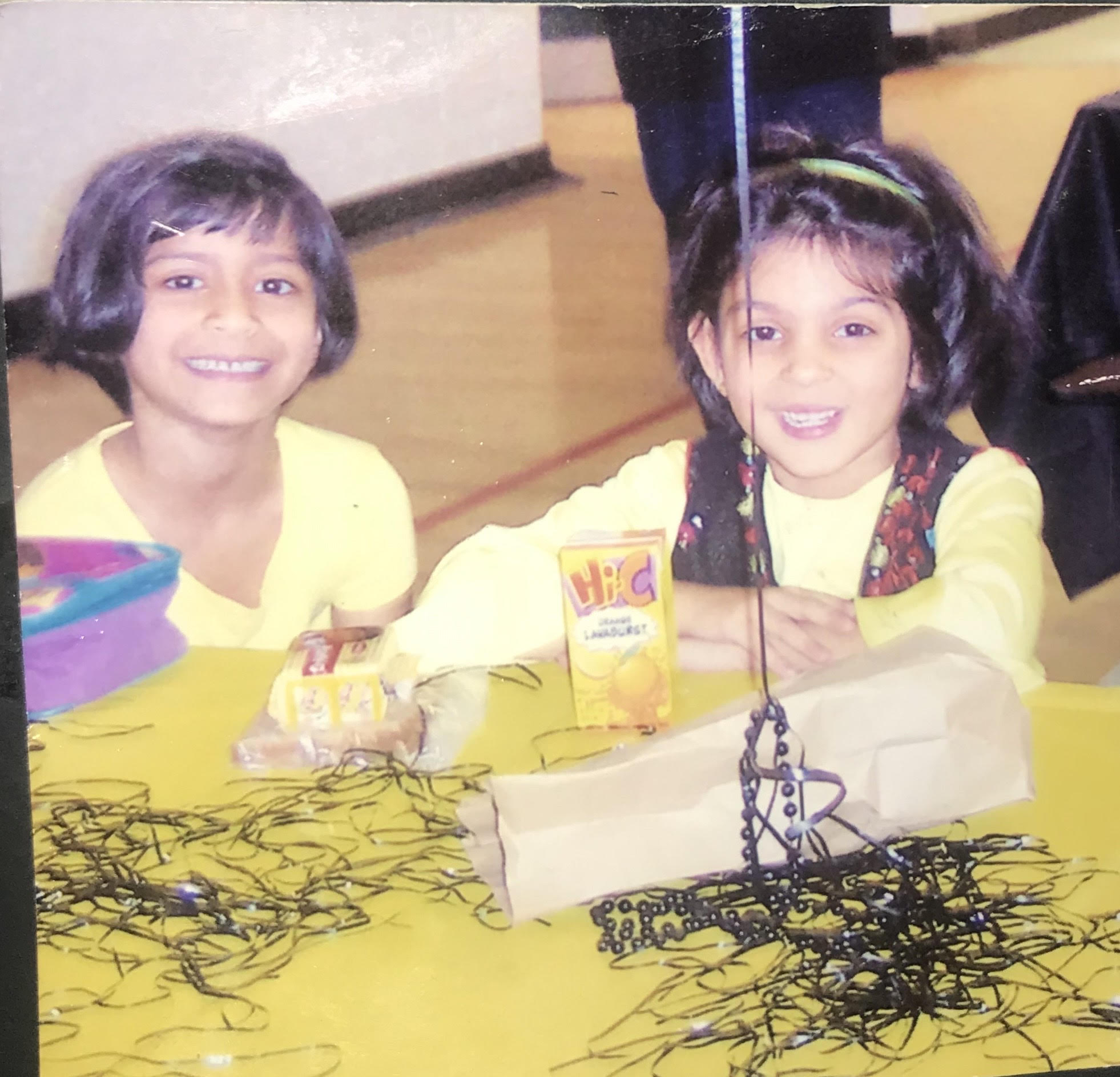

The perks of that meant school-based encouragement to excel and access to upper-income friends, she noted. The latter includes lifelong bestie Ritika Reddy. Reddy, whose mother is a pediatrician and whose father owns two convenience stores, is also the first in her family to be born in the U.S. She, too, attends Ohio State.

“Throughout our lives, we have definitely benefited from the model minority myth,” Pujara said of growing up with Reddy. “I don’t want to seem like I had it as bad as others.”

The two always had each other, as it was, another brown person with parents whose nation of origin was India. They ate the same foods, wore the same national dress for celebrations inside a broader Indian-American community, and attended the same Hindu Sunday schools and youth camps in Pittsburgh.

Yet, both born as 9/11 re-shaped American life, they said they have also experienced a particular immigrant-sparked form of racism that was in sharp contrast to a school and community life they each regard as positive.

Reddy shared two experiences, the first of which occurred in a middle school classroom.

In connection with a lesson, a teacher pointed out one white student and said he brought “successful businessman” to mind. Then directing attention to Reddy, he suggested an impression might be, “There is a terrorist with a bomb in her purse.”

“At the time, I didn’t realize what that meant,” Reddy said. “The other students laughed and I did, too. Later, I thought about it … I went back and talked to the teacher. We figured it out.”

Reddy had a similar experience in high school. In a conversation with a teacher who was reluctant to travel by air, she sought to reassure him.

“But, if you were on the airplane, I would be extremely scared to get on it,” the teacher startled Reddy by replying.

Pujara experienced a similar incident with a fellow student while in high school.

“I was going down the stairs at the end of the day and I heard a voice behind me,” Pujara said. “‘Hey, terrorist.’ He kept repeating it and I thought it was directed at me. Then I realized that it was directed at the Muslim student in front of me.”

Continuing her way on to practice for speech and debate, she surprised herself and others by breaking down in tears once she arrived. Pujara opted to later track down the student who spoke the words to tell him they were offensive. “It’s not a joke.”

INSIDER, OUTSIDER

The model minority myth may have been part of what made both women feel confident confronting those whose words hurt them. “It greatly benefited me,” Pujara said of the myth. “But, it hurts others other who are not Asian, particularly those who are black and Hispanic.”

That difference — the difference between being inside or outside of certain opportunities — really hit home for both women in their last year of high school. That year, a confrontation between black students and a group of white students identified by a slur suggesting low intellectual or socio-economic status briefly turned violent.

Both Pujara and Reddy heard about the incident from students and in a school assembly and were displeased, but neither saw it. They realized they barely knew the people involved. “There’s a barrier,” Pujara said. “We weren’t in the same classes.”

Ironically, that kind of insider/outsider issue is what sparked their parents’ immigration to America, Reddy noted.

“They came to work and to have the opportunity for a better life,” Reddy said.

For Pujara’s parents, the situation was similar. Her father, Haresh Pujara, came to the U.S. in the 1990s. His arrival was sponsored by his uncle, whose own immigration was made possible by his ability to teach business and economics at the college level. The uncle worked for what is now Wheeling University.

FULL CIRCLE

Varsha Pujara, Pujara’s mother, who arrived in the U.S. at age 21 after an arranged marriage, said she has truly enjoyed living in Wheeling in spite of a couple of immigration-related incidents on the job in recent years. (Two patients have refused to work with her. One passerby at the hospital suggested her “illegal” status would soon be discovered. Haresh and Varsha Pujara have been naturalized U.S. citizens since 1995 and 2008, respectively.)

“There are more good people than bad people,” Varsha Pujara said of overall life in America. “People here in Wheeling are so nice. That’s what’s made me stay here.”

She noted Pujara and her younger son, a 2020 Wheeling Park graduate, were born with American citizenship. She keeps that in mind when she encounters a bump in the immigrant road — or a literally homegrown petition to address such things.

“This is their homeland. This is their motherland,” she said of her children.

Varsha Pujara also pointed out that something interesting has come about in recent years, particularly during the long, odd days of COVID-19.

“I’m so thankful for ancestry.com,” she said of a nationwide interest in genealogy and, particularly, countries of origin. “Everyone came from somewhere. This is an immigrant country.”

• A long-time journalist, Nora Edinger also blogs at noraedinger.com and Facebook and writes books. Her Christian chick lit and faith-related non-fiction are available on Amazon. She lives in Wheeling, where she is part of a three-generation, two-species household.