Connections to place are powerful. The former residents of Power, West Virginia know this all too well. What do you do when your childhood village no longer exists?

While abandoned or “ghost” towns are not unheard of in West Virginia, especially in the central to southern parts of the state where coal mining was prevalent, Power does not show up on any ghost town lists. Even though Power was closed almost five decades ago, it has recently been a topic of local conversation, including coverage from numerous news outlets and an article by Archiving Wheeling. However, while the history of Power is compelling, the people of Power are still here and their stories are fascinating.

The Windsor Power Plant

The Windsor Power Plant broke ground in 1915 and started operating in 1917. The Village of Power was created as a community and place to live for the employees and their families. The company bought houses from army barracks and began setting up the town.

The Windsor Power Plant was not only special because of the community it created in the Ohio River Valley, but it was also historic and groundbreaking for its time. It was jointly owned by the Ohio Power Co. and the West Penn Power Co., a highly unusual practice that would later become widely popular. Before Windsor, most power plants were smaller and built locally in the communities they were intended to serve. Being ideally located close to both sources of coal and water, a “mine-mouth” design, the Windsor Power Plant “revolutionized the industry” by being able to transmit energy much further distances.1

Nicknamed the “Granddaddy of Power,” one of the most notable impacts of this technology was the first 138,000-volt transmission line in the US, which carried power to Canton, Ohio, 55 miles away.2 That power enabled the industries in Canton to generate the supplies needed for the US military to fight in WWI. While the Plant, its contributions to the industry, and its reverberations throughout the Ohio River Valley are documented in various historical records—it is the people of Power who truly make sure the nation never forgets their home.

1American Electric Power. Boundless Energy: Past, Present, Future. United States: Pacioli Press, 2018. Accessed October 16, 2020. https://www.aep.com/Assets/docs/about/AEPHistoryBook-BoundlessEnergy.pdf.

2“Windsor Power Plant to Close,” The Weirton Daily Times, June 27, 1972, 9.; American Electric Power. Boundless Energy: Past, Present, Future.

The People of Power

At its peak, there were 100 “company” houses in Power, all owned by the Windsor Power Plant. To live in a company house, someone in the family had to work at the Plant. Residents paid a monthly rent, but everything else, including utilities and maintenance, was taken care of by the company.

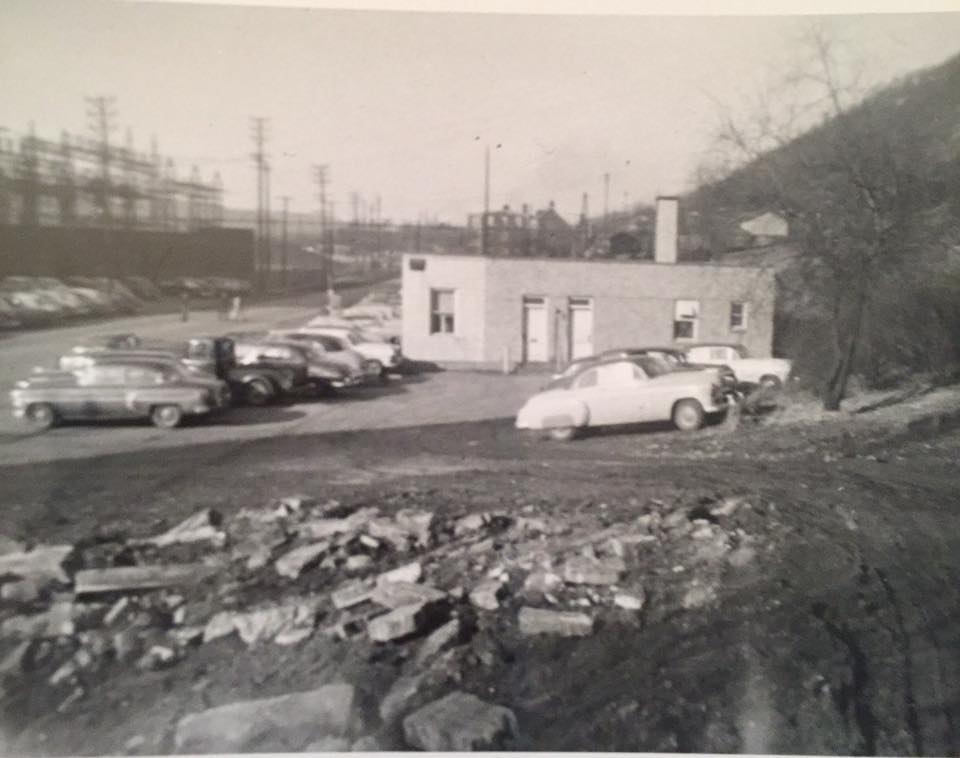

Eventually the Village became self-sufficient. Men would walk to work at the nearby Plant and residents could get almost anything they needed in town. There was a restaurant and a general store, where you could buy on credit and settle every month. There was a post office where every family had a P.O. box, a playground for the children, a barber, a doctor, a community hall that hosted dances, parties, and meetings, and even a two-lane bowling alley.3 If someone desired anything they could not get in Power, Wheeling was a short bus ride from a stop along Route 2.

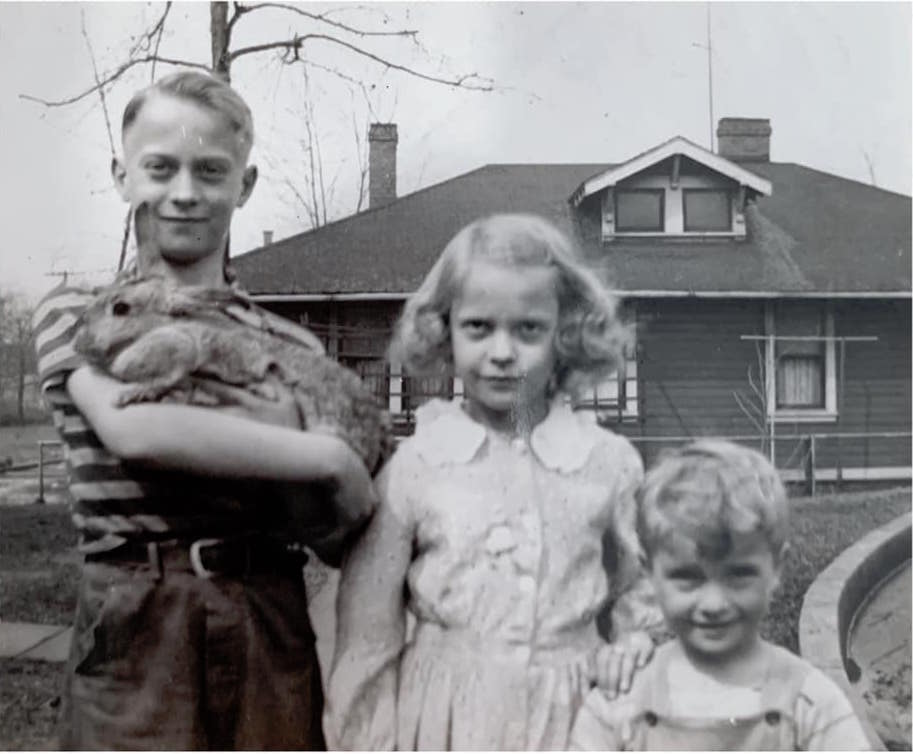

Former residents of Power describe an incredibly close-knit community—one where “everyone knew everyone,” a recurring sentiment from numerous people. Most who are still alive spent their childhood and adolescence in Power, but not their adult lives. By the time many of them came of age, they had either moved away or the town had closed. Although all former Power residents are retirement age or older, their stories and memories still retain a childhood fondness and nostalgia. What ties them together are their similar memories of playing or watching ball games on Plummer Field, sledding during the winters, bowling or playing euchre at the bowling alley, fishing or swimming in the creek, and more.

All of the interviewed former residents emphasized again and again how wonderful it was growing up in Power. Jack Ernest describes it as a “Currier and Ives painting.” As a child, it was safe to run around in the Village and everyone knew you had to be home when the streetlights came on. Susan Cunningham loves thinking about how “the friendships that were established remain today.” Since it was such a small village—and before the age of computers, video games, and cell phones—the children of Power would spend their time outside all playing together. Children were constantly running, playing dodgeball, trying to catapult a friend off the seesaw, and more. To this day, Ginny Ernest-Taylor still carries scars on her chin from a sledding accident. Her brother, Jack Ernest, recalls occasionally secretly washing neighbors’ cars parked on the street. And, whoever’s house you were closest to at lunchtime was where you would get invited in for a break and a meal.

Having the freedom and the outdoors to explore as a child also created mischief. Jack describes how he and the other Power boys would often go to the water tank that served the Village. They would climb up the ladder on the outside, open the lid, shimmy down the inside ladder, and go swimming. “People would turn on their taps and wouldn’t know that we were swimming in the drinking water!” Jack remembers gleefully and concludes, “growing up, we just had a blast.”

Of course, the tight community had its drawbacks too. Although currently in his 80s, Neil Patterson still recalls with a chuckle that “if we got in trouble and someone found out…that someone usually worked with my dad at the Plant and then I would get in trouble come dinnertime.”

While childhood in Power was described by many as idyllic, many former residents made sure to specify how there was an expectation of hard work and contribution in many of the families. Neil Patterson and other Power boys used to earn about $2 a night in the 1940s setting up pins at the bowling alley. Jack Ernest remembers going hunting, even as a young boy, and bringing back game to put on the table or picking up odd jobs to earn a bit to put towards his school clothes. Jack, who served in the Marine Corps during the Vietnam War and later returned to the country as a Christian missionary, credits his Power childhood with many of the values and the work ethic that he brought to his humanitarian aid projects.

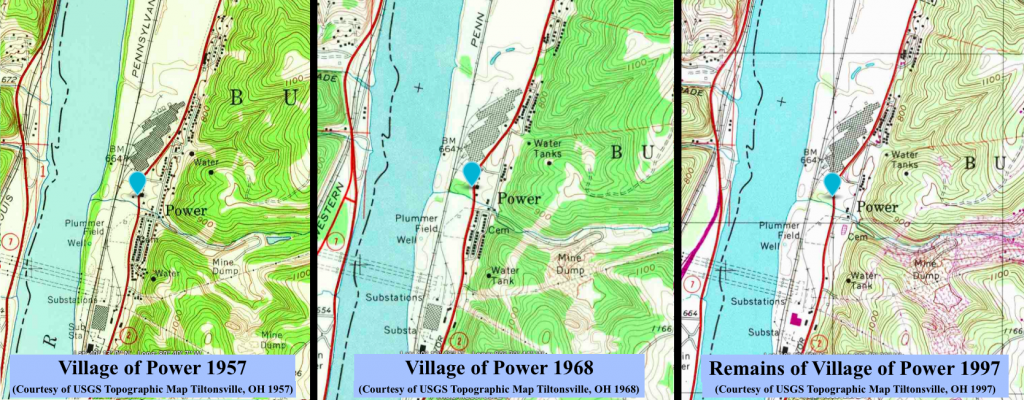

Despite once being a leading pioneer in electric production, the Windsor Power Plant eventually became too expensive to update, especially to adhere to new pollution restrictions and standards. In 1973, after a strike by workers, the company decided to close the Plant permanently. All of the company houses and buildings in the Village of Power were demolished or dismantled and removed and the main streets were filled in.3 Residents were given notice and many employees were either offered a transfer to a different plant or retired. Some families stayed in the area and moved to neighboring towns, but some relocated further away; the community was irreparably impacted.

Although he no longer lived in Power, Jack Ernest remembers it being “heartbreaking when the Plant shut down and all the houses were demolished; there went my treasured childhood.” Other former residents, like Neil Patterson, express nostalgia but say that “it’s just the way the world turns. There’s nothing you can do about it. It’s progress. Pull up your britches and go with it.”

3“Power,” Brooke County Genealogy, accessed October 5, 2020, https://brookecountywvgenealogy.org/power.html

Phantoms of Power Today

The memory of Power is kept alive by an active group of former residents and descendants. On a private Facebook page started in 2012, members share photos or remembrances every few days. They raised money and support to create the Power Memorial Park, which was dedicated in August 2020. It is located along Route 2, just south of Beech Bottom, and is complete with a state historical marker, benches, flagpole, and a memorial dedicated to the Power veterans who served in the military. The Memorial Park is the former site of Wickham’s Store, which included a general store, post office, and restaurant; it served as a central gathering location for the community to shop, get their mail, and hear the daily news or gossip. Jack Ernest gave an address at the dedication and recalls thinking about how he was a mere 50 yards from the spot where he was born—where there is now nothing.

Today if you were to pass by the former site of Power, a place that hundreds of people once called home, you would barely notice anything. If you walk/run/bike/skip on the Brooke Pioneer Rail Trail, you will pass a historical marker with picnic tables honoring Power. On the river side of the trail is where Neil Patterson recalls victory gardens growing during WWII. If you squint, you can almost see the old men tending their gardens before kicking back and cracking open a beer as Neil remembers. If you pulled to the side of Route 2, you might glimpse the steps leading up to the Clendenen Family Cemetery, which is virtually all that is left of the main Village. The former streets are overgrown with wildflowers and the former Plant is unrecognizable. If you take a closer look, you might notice the ghosts of what are the original sidewalks, leading off into the underbrush…

To learn more about the history of Power and the impact of the Windsor Power Plant in the Ohio River Valley, click here to visit Archiving Wheeling. Special thanks to Susan Cunningham, Jack Ernest, Ginny Ernest-Taylor, Neil Patterson, and Juli Simmons.

• Emma Wiley, originally from Falls Church, Virginia, was a former AmeriCorps member with Wheeling Heritage. Emma has a B.A. in history from Vassar College and is passionate about connecting communities, history, and social justice.