Wandering around some of Wheeling’s graveyards, you might see some gravestones with dates older than the cemetery itself.

How can that be?

Answer: For many residents of Wheeling’s existing cemeteries, this was not their first resting place.

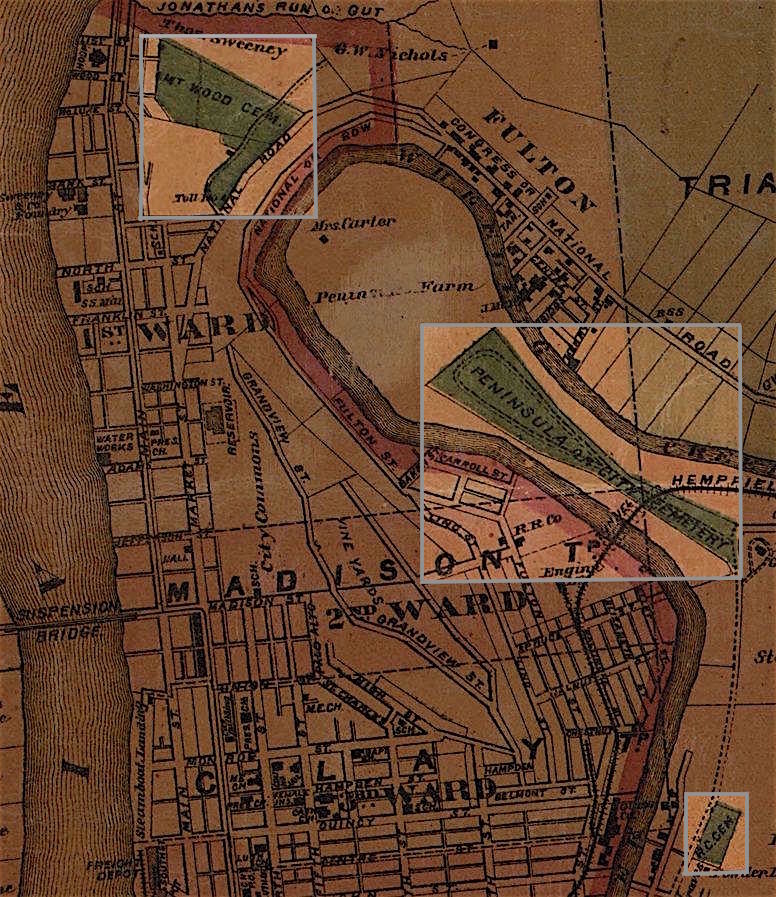

When asked to identify a Wheeling cemetery, most residents would probably point to Greenwood or Mt. Calvary. Some might bring up Mt. Wood or Peninsula as historic, older examples. But most would be surprised to know just how many cemeteries and burying grounds Wheeling has had over its time and how many have been lost. Most of Wheeling’s earliest cemeteries were located closer to the center of town. As the city grew, the cemeteries that were built on what were the outskirts, were now taking up valuable real estate. As these early burying grounds were dismantled, the remains had to be relocated. There is a long and complicated history of moving bodies between cemeteries in Wheeling.

A City Expanding

In Wheeling, the most common reason for relocating bodies was the deconstruction of a cemetery. The burying ground known as the “First Cemetery” was located around 9th Street on the west side of Main Street, but only existed until around 1818. As the city grew larger and more space was needed, the cemetery was replaced by the Northwestern Bank. The majority of the remains were probably moved to Hempfield Cemetery, which was located on 16th Street, where the Ohio County Public Library is today. Decades later, after the bank moved to a new location, George Wheat was building his new house on the site when he discovered “a large number of bones, relics of the graveyard, which he boxed up and buried in Greenwood.”1

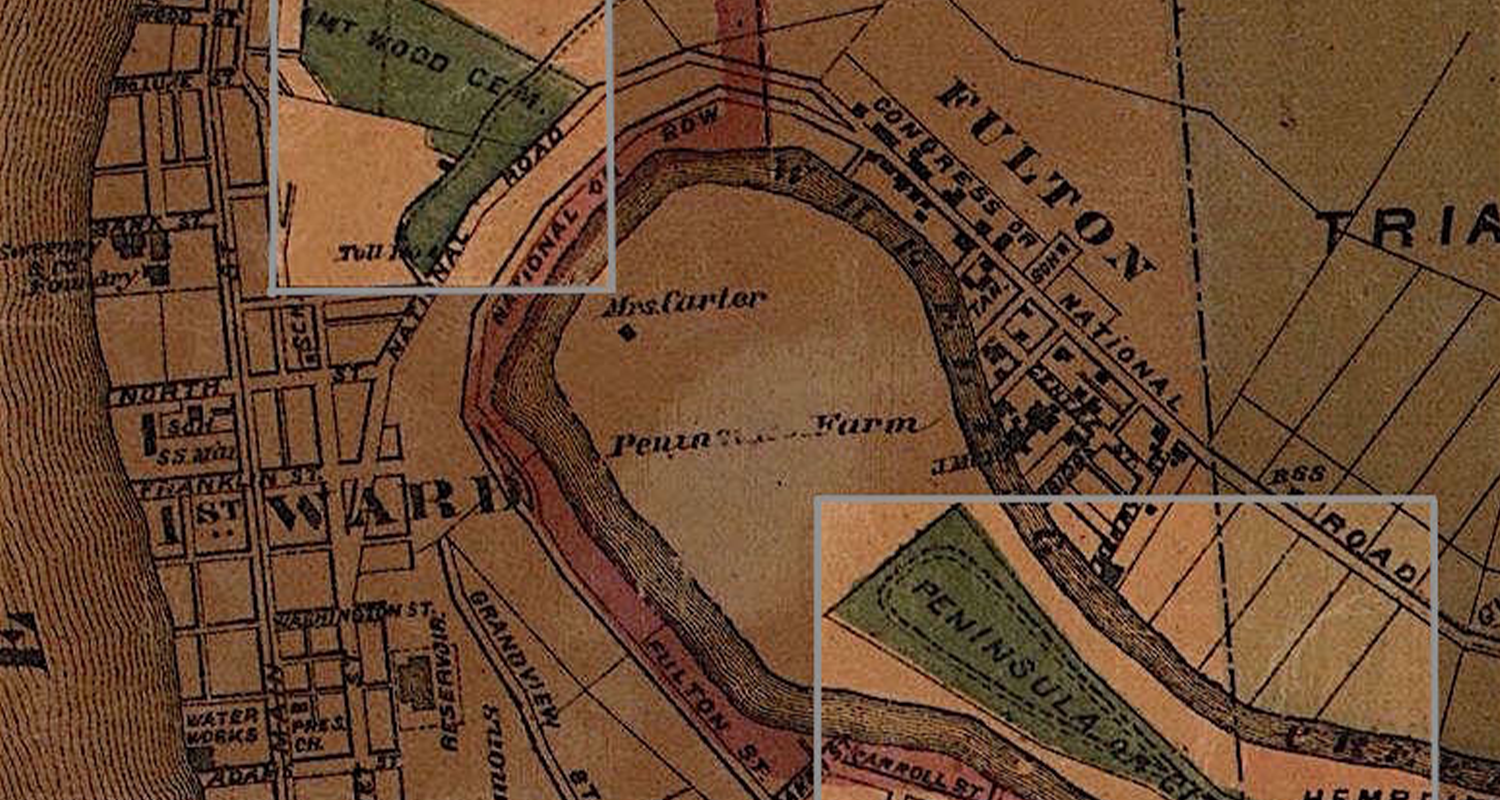

Even though Hempfield Cemetery started out on the outskirts of town, Wheeling quickly expanded, surrounding the graveyard with buildings. As the railroad expanded west, the Hempfield Railroad Company began looking for a site for a depot yard and eventually settled on the cemetery in the early 1850s. Since Hempfield was a primary burying ground for many of Wheeling’s residents, its impending closure encouraged the creation of the Mt. Wood, Catholic, and Peninsula cemeteries. Most of the remains from Hempfield were reburied in these cemeteries, in addition to the East Wheeling Cemetery, located further east at the convergence of 16th and McColloch Streets. A Wheeling newspaper article from the 1930s claims that as many as 4,500 bodies were moved.2

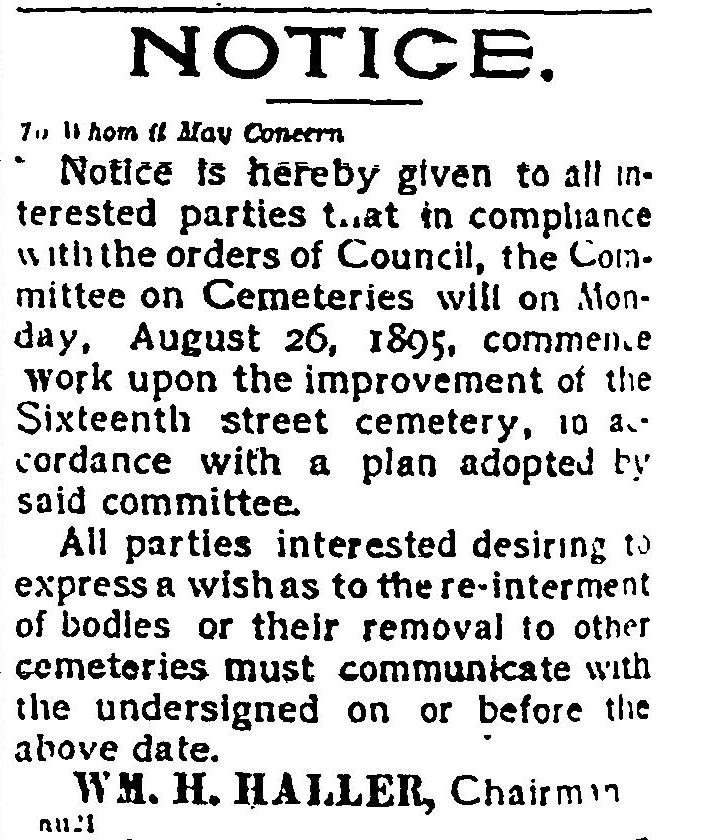

Decades later, the East Wheeling Cemetery was also at risk for destruction. The ground had not been maintained and numerous complaints of children and livestock being allowed to run rampant had made it an undesirable place to be laid to rest. As early as 1889, the Council Committee requested that Wheeling residents make arrangements to remove their dead from the cemetery.3 Later that year, the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer reported that “bodies are being removed from the old East Wheeling cemetery at the corner of Sixteenth and McColloch streets, to other cemeteries, at the rate of from ten to twenty a week” and that “nearly all the bodies taken up are in a dry, mummified condition.”4 However, over six years later, in 1895, there were still notices in the newspapers asking for bodies to be removed. In late August 1895, work was planned for the next week, giving Wheeling residents one final chance to remove their loved ones by August 26th or “forever after hold their peace.”5

Other Reasons for Remains Relocation

Even once the city stopped removing cemeteries for expansion reasons, a new threat emerged. The construction of the highway systems through and around Wheeling knocked out or altered several graveyards. Peninsula Cemetery’s land had already been tunneled beneath with the Hempfield Railroad Tunnel, but the construction of I-70 in the mid-1960s drove directly through the middle of the graveyard. Thousands of remains were moved to other burying grounds and the cemetery was irreconcilably split in two.6 To this day, people still get confused when they happen across the southern end of the Peninsula Cemetery at the top of Rock Point Road, now labeled “Manchester Cemetery.” Even though it used to be the main entrance to Peninsula, the few graves that remain are now decrepit and largely forgotten.

While most of the bodies moved in Wheeling were due to city expansion or construction, there were more personal instances. For example, before the 1850s, there was no specified Catholic burying ground in Wheeling, so Catholics dispersed their dead among the other cemeteries. When Hempfield closed, the Catholic community, led by Bishop Whelan, decided to look for a site for an exclusively Catholic cemetery. They bought land off the Reilly estate in the Manchester neighborhood, north of Reymann’s Brewery on Rock Point Road, and proceeded to move the Catholic dead not only from Hempfield, but from all the other graveyards where Catholics had been buried.7 When this Catholic cemetery in Manchester quickly became full, Mt. Calvary opened on National Road and bodies were transferred yet again.8

Interestingly, it is not only adherence to faith that motivates personal reasons for relocating bodies from existing cemeteries. Many of Wheeling’s cemeteries have documented cases of people disinterring their loved ones in order to rebury them in a more desirable location—even though the original cemetery continues to exist to this day—or to be with the rest of the family. A prime example is the prominent Captain John List, whose family moved his remains from Mt. Wood to Greenwood Cemetery after Mt. Wood had become less fashionable.

Disturbing Disturbances

While many of Wheeling’s former residents were relocated with love and care by friends or descendants, unfortunately, there is evidence of not all the dead being treated as such. Bones were separated and some carried off, bodies of different people were jumbled together, and gravestones disassociated with their owners.

One of the most disturbing accounts was at the Eoff/Chapline Cemetery that used to exist in Center Wheeling, on 23rd Street east of Eoff Street. While the cemetery had housed generations of Wheelingites, by the 1890s, the ground had not been maintained and was starting to degrade. There were numerous reports of bones washing into the street during particularly heavy rains or locals absconding with tombstones to use as construction material.9 A Wheeling Register article from 1892 described the fate of part of the cemetery as a road was being built:

“A Register reporter was on the scene yesterday afternoon and watched the progress of the work of excavation for some time. On the side of the bank at a depth of about six feet below the surface, projected a half dozen coffins. The ends were chopped off and the bones pulled out and thrown into the carts. They were then hauled to the creek bank, near the Whittaker mill.”10

Subscribe to Weelunk

At one point, when it was first created, the ground was made up of two separate burying grounds. According to the newspaper in 1880, the space in between the two was where Black people in Wheeling were buried. However, that section was the first to be disinterred when the city created a road and the bodies were reinterred elsewhere.11 Little is known, documented, or even remembered about these people whose supposed final resting place is paved over.

Larger History of Body Relocation

While Wheeling might have a particularly complicated and extensive history of moving dead bodies, it is unfortunately, not unique. Many towns and cities have their own examples of relocating bodies for a variety of reasons—some are well documented, and others have been disorganized and the remains misidentified, mistreated, or lost.

As a whole, the removal of dead bodies in the United States has a far more sinister history of practice. In the mid-19th century, as medical schools were in need of cadavers to practice their skills, grave robbing and body trafficking became a lucrative business.12 As an even longer practice, archaeologists, scientists, doctors, and others disinterred hundreds of thousands of indigenous peoples’ remains and funerary goods to send to the premiere museums, private collections, and other institutions. Despite the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in 1990, indigenous peoples are still fighting for the return of their ancestors and cultural items.13

Conclusion

With some cemeteries being dismantled, new ones opening, and bodies being moved for a variety of reasons all over the place, it is safe to say that there has been a fair amount of confusion regarding Wheeling’s cemeteries. Due to the numerous cemeteries that were dismantled in Wheeling, some remains were disinterred at least twice, possibly three times. No rest for the dead.

While the past often feels like a foreign place, it is not so far behind us as we’d like to imagine. As recently as late 2013, construction workers discovered and disinterred a partial human skeleton and a large grave marker while excavating at the site of the former East Wheeling Cemetery. The Intelligencer article about the discovery notes that the human remains were to be reburied at Peninsula and the grave marker transferred to Mt. Wood.14

Cemeteries seem like such permanent fixtures on a city’s landscape, but Wheeling’s history proves differently. Many current residents walk, play basketball, or read books on the sites of many of Wheeling’s former cemeteries—never realizing what once lay under their feet. Much of the remaining evidence of these relocations lay in old maps or as dates inscribed on crumbling tombstones, older than the cemetery itself.

Special thanks to Bekah Karelis for her extensive previous research and conversation about cemeteries.

• Emma Wiley, originally from Falls Church, Virginia, was a former AmeriCorps member with Wheeling Heritage. Emma has a B.A. in history from Vassar College and is passionate about connecting communities, history, and social justice.

References

1 “Our Silent Cities: A History of the Cemeteries in and Around Wheeling, Which will be of Interest to Many of Our Readers.” The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, December 8, 1880.

2 “Railroad Yards Supplant One of City’s Early Burial Plots,” Wheeling Sunday News, March 22, 1931.

3 “The Deserted Cemetery,” Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, July 6, 1889.

4 “Digging Up Old Citizens,” Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, September 26, 1889.

5 “Care of Cemeteries,” Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, August 20, 1895.

6 “All’s Quiet on Home Front,” Wheeling News Register, March 17, 1991.

7 F.W. Beers & Co., and J.M. Lathrop, Map of the “Panhandle” embracing counties of Hancock, Brooke, Ohio and Marshall, West Virginia, [S.1,: Geo. Nichols, I. D. Hall, D. L. Miller, W. R. Dumond, I. F. Manchester and C. J. Corbin, 1871] Map, https://www.loc.gov/item/2007633928/.

8 “Our Silent Cities: A History of the Cemeteries in and Around Wheeling, Which will be of Interest to Many of Our Readers,” The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, December 8, 1880.

9 “Skull and Crossbones: Displacement of Skeletons from the Fifth Ward Cemetery,” Wheeling Register, June 22, 1880.

10 “Graves Desecrated: Workmen Excavating for a Street in the Old City Cemetery: Coffins and Their Contents Turned Out by Pick and Shovel, and Carted Away to be Dumped in the Creek,” Wheeling News-Register, August 9, 1892.

11 “A Melancholy Sight: The Graveyard in Centre Wheeling as it Now Appears,” Wheeling Register, July 2, 1880.

12 Antero Pietila, “In Need of Cadavers, 19th-Century Medical Students Raided Baltimore’s Graves,” Smithsonian.com. October 25, 2018. Accessed November 17, 2020. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/in-need-cadavers-19th-century-medical-students-raided-baltimores-graves-180970629/.

13 American Indian Liason Office. “Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA): A Quick Guide for Preserving Native American Cultural Resources,” National Park Service, 2012, accessed November 17, 2020, https://www.nps.gov/history/tribes/documents/nagpra.pdf.

14 Ian Hicks, “Bones, Graves Found,” The Intelligencer Wheeling News-Register, November 3, 2013, https://www.theintelligencer.net/news/top-headlines/2013/11/bones-grave-found/.