The sudden closure of Ohio Valley Medical Center in 2019 came as a shock to the community. Employees scrambled to find new jobs, patients sought new doctors, and the Ohio County Library and OVMC Alumni association joined forces to preserve what they could of 127 years of Wheeling’s medical history.1

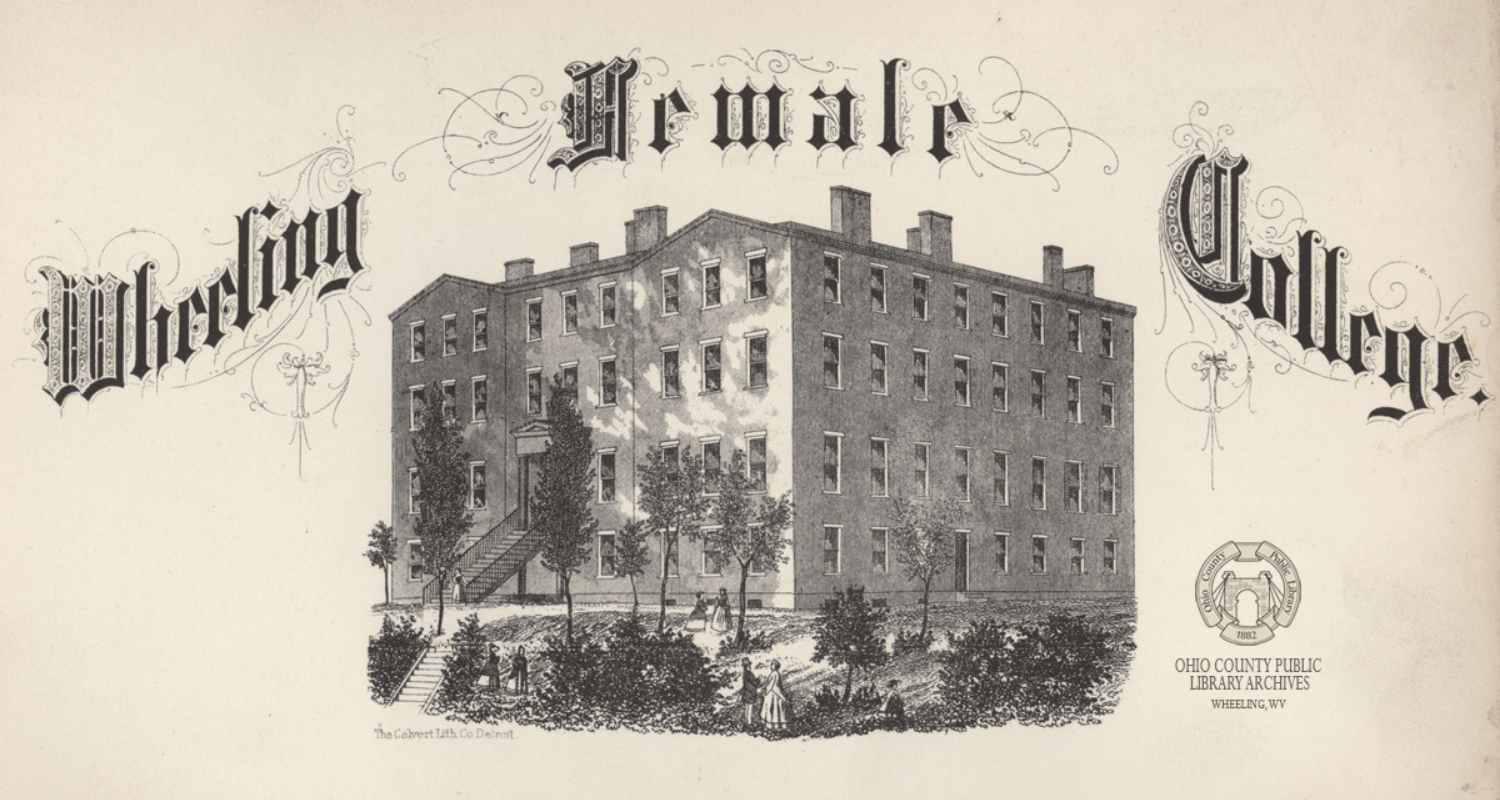

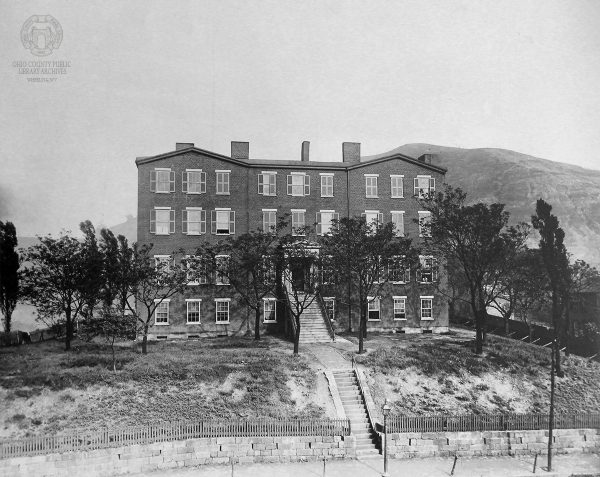

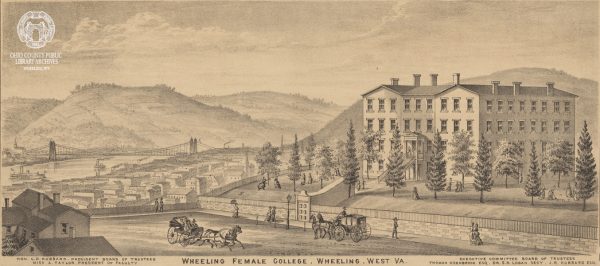

128 years earlier, Wheeling Female College faced a similar predicament. Situated on the site that would become the OVMC, it had been struggling financially for years when the president of the college, Rev. H.R. Blaisdell, abruptly announced his resignation on account of insufficient pay and Wheeling’s “severe winters.”2

The combination of factors proved fatal, as the Wheeling Daily Register reported in January 1891: “The school is closed in the middle of the school year, the faculty is disbanded, and the scholars have gone to their several homes.”3 The idea of turning the college into a hospital quickly gained traction, and within a year it reopened as Wheeling’s City Hospital.

Although few would dispute the hospital was an effective way to repurpose the building, it’s worth pondering what Wheeling lost when its female college closed its doors. The late nineteenth century was period of rapid change for women’s education nationwide. Colleges such as Bryn Mawr were revamping their curriculum and architecture to reflect the idea that women could benefit from the same robust education and independent college life as men.4

What might Wheeling have looked like if, at the height of the industrial era, it had reaffirmed its commitment to women’s education? As it was, the Intelligencer lamented, the closure left “Wheeling without a young ladies’ seminary such as a city of this size should have.”5 A survey of surviving documents from Wheeling Female College, including decades of school catalogues, suggests that before its closure the school reflected broader trends of expanded educational access and opportunity for white, Protestant women.

The institution first opened its doors as the Wheeling Female Seminary in 1848. We associate the word “seminary” today with theological training for ministers, but in the nineteenth century it carried a broader vocational emphasis.6 Female seminaries were religiously-affiliated, private boarding schools that educated women in modern subjects while also cultivating values of feminine comportment, piety, and discipline. Often focused on teacher training, seminaries began proliferating in the early 1800s in the United States as part of a larger revival of religious enthusiasm and educational reform efforts.7

Wheeling Female Seminary’s 1858 Catalogue reveals the inner workings of the institution. Steered by an all-male Board of Trustees and President, Samuel Ott, the non-sectarian school enlisted an almost exclusively female teaching staff, including Principal Mrs. Sarah R. Hanna.8 This administrative structure was typical of female seminaries at the time, reflecting the assumption that male oversight was a necessary component of the female educational experience.

The school included preparatory, junior, and senior departments offering a wide range of subjects to preteen and teenage girls: Arithmetic, U.S. History, Science of Government, Geology, Chemistry and Literature. For an additional fee, parents could secure for their daughters lessons in piano, guitar, needlework, watercolors, elocution, and Latin, and other suitable pursuits.9

In Wheeling, as elsewhere, monitoring student behavior and socialization was a foremost concern. Female seminaries did not seek to emulate the peer camaraderie and freewheeling debate of male colleges; rather, they saw it as their duty to protect the feminine virtue of their young charges. Principal Hanna assured parents and patrons that “all necessary safeguards” were being adopted for the “protection of health, morals, and social intercourse” of students. One such safeguard was to house only two women to a room, thus teaching pupils “to form habits of order and delicacy, and enjoy better opportunities of uninterrupted study.”10

Funded by private donations, Wheeling Female Seminary faced financial difficulties from the start. In 1859 Principal Hanna warned the Trustees that they “would not be able to continue the school” unless actions were taken to reduce expenses.11 Under these dire circumstances, Wheeling Female Seminary eventually closed and reopened under new leadership as Wheeling Female College in 1865.

The institution’s transition to a full-fledged college brought notable changes to the curriculum. During its first full academic year, the college offered senior-level courses in “Legal Rights of Women” and “Health of Women,” suggesting a politically progressive bent for the new institution.12 Such conclusions should not be taken too far, however – that same year, college leaders emphasized they had no intention of offering the same intellectual training as male colleges: “The true basis of a young lady’s education…[is] to pursue such studies as her position in society and her womanly nature demand, and to undertake no more than she can master.”13 “Legal Rights of Women” also disappeared from the school’s course of study after 1866, suggesting it may have faced some backlash from stakeholders.

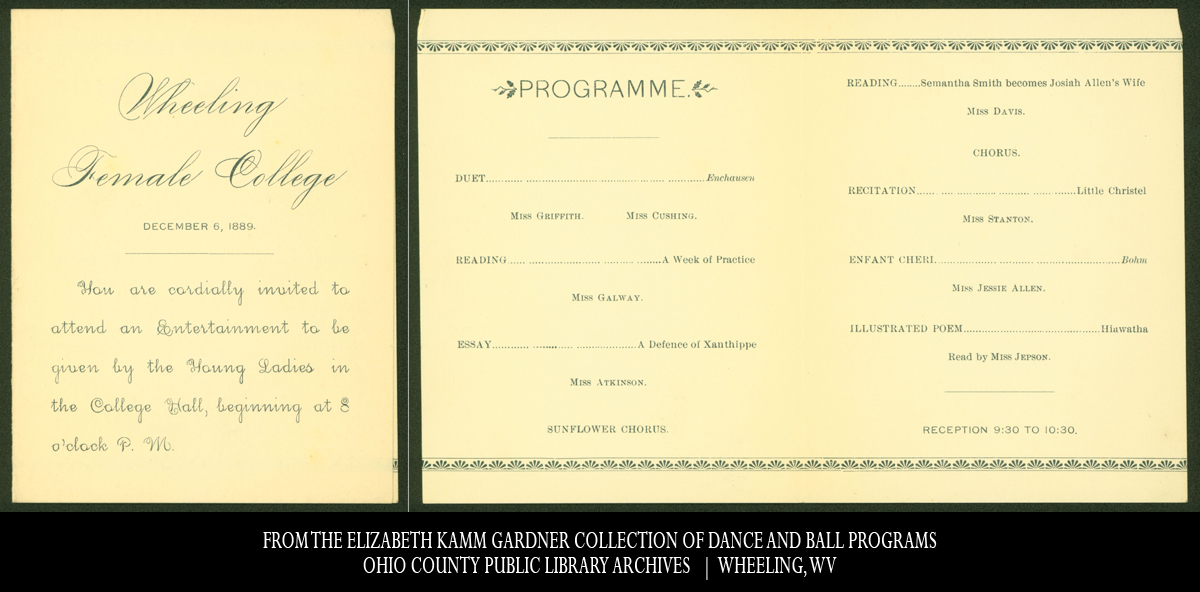

Wheeling Female College nonetheless gradually began to reflect the hallmarks of a modern education for women. By 1870, the school had added a post-graduate course of study to its collegiate and teacher’s training curriculum.14 Two literary societies, Minerva and Sigourney, provided opportunities for extracurricular socialization and an alumni association cemented lifelong bonds among students.15 The college also began offering physical education instruction, a change consistent with the idea that women’s health would benefit from more freedom of movement.16 By 1890, one year before the college shuttered permanently, the institution had graduated 278 “cultured and intelligent women.”17 One notable graduate was Dr. Harriet B. Jones, the first woman licensed to practice medicine in West Virginia.18 Another was Methodist missionary Isabella Thoburn, founder of Lucknow Female College in Lucknow, India, which survives today as Isabella Thoburn College.19

While access to higher education was revolutionary at the time, it was only available to a finite group of women. The Wheeling Female College extended educational opportunity to a small, elite group of white, Protestant young women. As Wheeling Female Seminary, the school coexisted with slavery and it is possible the families who patronized the school owned some of the 100 enslaved persons resident in Ohio County in 1860. After the Civil War, as Jim Crow segregation laws spread across the nation, West Virginia’s 1872 Constitution decreed, “White and colored persons shall not be taught in the same school.”20

The college also opened, in part, as a counterpart to Catholic offerings in the area. An 1870 Pittsburgh Advocate article quoted by college expressed its approval that the college offered an alternative to the “baneful influences” of the nearby DeChantal Seminary, a Catholic institution the Advocate further disparaged as a “half educational, half convent” school.<21

Closing as it did in 1891, Wheeling Female College left behind an unfinished legacy. It had not yet fully embraced the independent, career-minded “New Woman” ideal, but it showed signs that it was headed in that direction. President Blaisdell, on the eve of his resignation, showed frustration that despite its material success, Wheeling had not done more to support women’s education. “Our people have the money to educate their girls,” he lamented, but instead, “Scores of young ladies in Greater Wheeling are wasting the abilities their Creator has given them in the inanities that satisfy not.”22 His final bid for an endowment for the college unheeded, Blaisdell left for sunnier climes.

Although Wheeling Female College did not survive into the twentieth century, the educational legacy of the site did not disappear entirely. The School of Nursing that opened as part of Wheeling City Hospital in 1892 was the first of its kind in West Virginia, opening up career paths for generations of Ohio Valley women.23

If you’d like to learn more, the Ohio County Public Library has published a survey of surviving documents from Wheeling Female College, including decades of school catalogues on their website. Click here to check it out.

References

1 Kelly Strautman, “Held together by Stories: A Special Lunch with Books Remembers OVMC,” Weelunk.com, January 11, 2020. https://weelunk.com/54875-2/

2 “President Blaisdell Resigns,” Wheeling Daily Register, January 3, 1891, 4.

3 Wheeling Daily Register, January 5, 1891, 2.

4 Dr. Helen Horowitz, “The Dangerous Experiment: The Building of the Seven Sisters Colleges,” National Women’s History Museum, August 9, 2018, https://www.womenshistory.org/articles/dangerous-experiment

5 “A Seminary for Wheeling,” Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, January 5, 1891, 4.

6 Horowitz, “The Dangerous Experiment.”

7 Keith Medler, “Mask of Oppression: The Female Seminary Movement in the United States” in History of Women in the United States, Vol. 12: Education, ed. Nancy Cott (Munich: K.G. Saur, 1993), 28.

8 1858 Catalogue of the Officers and Students of the Wheeling Female Seminary, Ohio County Public Library Special Collections, 2.

9 1858 Catalogue, 9-10.

10 1858 Catalogue, 12-13.

11 Minutes of Board Meetings, Wheeling Female Seminary, June 1859, Ohio County Public Library Special Collections.

12 Catalogue of Wheeling Female College, 1865-1866, Ohio County Public Library Special Collections, 12.

13 Catalogue, 1865-1866, 14.

14 Catalogue of Wheeling Female College, 1869-1870, Ohio County Public Library Special Collections.

15 Catalogue of Wheeling Female College, 1889-1890, Ohio County Public Library Special Collections, 17.

16Catalogue, 1889-1890, 24.

17Catalogue, 1889-1890, 13.

18 Emma Wiley, “Wheeling’s Historic Female Doctors,” Weelunk.com, April 1, 2021. https://weelunk.com/wheelings-historic-female-doctors/

19 Paul Jeffrey, “Living the Legacy in India,” Response, March/April 2020. https://www.unitedmethodistwomen.org/news/living-the-legacy-in-india

20 Seán Duffy, “Wheeling’s Twentieth Man: 250 Years of Race Relations in the Northernmost City of the Southernmost Northern State,” Weelunk.com, July 6, 2020. https://weelunk.com/wheelings-twentieth-man-250-years-of-race-relations-in-the-northernmost-southern-city-of-the-southernmost-northern-state/

21 Circular of the Wheeling Female College, 1870, Ohio County Public Library Special Collections, 5.

22 Catalogue, 1889-1890, 30.

23 Strautman, “Held Together by Stories.”