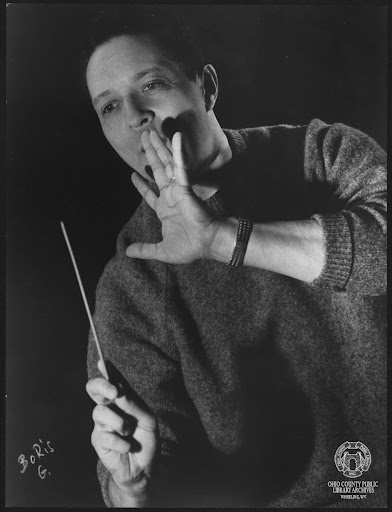

It’s 1945. You are sitting down, in your best formalwear, clutching a playbill that reads “On The Town.” The show has been running for 9 months, gaining exciting buzz. People couldn’t stop talking about the composer, Leonard Bernstein. The story of three sailors on shore leave in New York City has struck a chord with audiences and has people humming the popular song “New York, New York.” As the lights dim and the conductor takes up his baton, you are about to experience history. Everett Lee, the man holding the baton, is the first Black man to conduct a show on Broadway. And he was from right here, in Wheeling.

August 31, 1916, Everett Astor Lee was born to Everett Danver Lee, a barber, and Mamie May Blue Lee, a homemaker, on Eoff Street in East Wheeling. Everett’s talent shone at an early age. By eight, he had taken up the violin. He received lessons from Walter Rodgers of South York Street on Wheeling Island. It was here that he began practicing the skills that would make him famous. His family took note of his rising musical promise and made a tough decision to leave their home in Wheeling. They moved to Cleveland, where they hoped to further expose Everett to the arts. After a chance meeting in an elevator with Artur Rodzinski, the conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra, Rodzinski began acting as a mentor to young Everett. In 1948, Everett spoke of the importance of this early relationship; “My early conducting aspirations were nurtured by him…Rodzinski helped me in many ways; he would go over scores with me and give me pointers.”

After graduating high school, Lee enrolled in the Cleveland Institute of Music, where he honed his skills further. He enlisted in the army after graduation, but an injury ended his career and sent him back to Cleveland. He soon got a call from legendary Broadway producer, Billy Rose, to come and join the orchestra for a production of “Carmen Jones”, a retelling of the 1875 opera “Carmen”, featuring an all-Black cast. The story goes that the show’s conductor was snowed in for an evening performance, prompting Lee to move from the concertmaster’s chair to the conductor’s podium. From there, Lee would take spells conducting Goerge Gershwin’s “Porgy and Bess” before the fateful call from Leonard Bernstein came.

Conducting for “On The Town” did open doors for Everett Lee, but he found himself trapped by prejudice. He added to his resume further by playing violin in the New York City Symphony and conducting Boston Pops. He dreamed of playing with the New York Philharmonic, where his mentor Rodzinski was conducting at the time. Rodzinski, though, refused to let him audition, trying to spare him the ‘inevitable’ result he would face as a Black man trying out for a non-integrated orchestra. Not one to stop playing for anything, Lee created the Cosmopolitan Little Symphony in 1947, an integrated ensemble in which Lee made a point to program Black composers. Lee wrote to Bernstein of his ensemble; “My own group is coming along fairly well, it may be the beginning of breaking down a lot of foolish barriers.”

While Lee had trouble breaking down barriers in America, he found a welcoming home in Europe, which he moved to in 1957. He founded an orchestra in Munich’s Amerika Haus. He led traveling opera companies and conducted the Berlin Philharmonic before settling down in Sweden, where he was the conductor of the Norrkoping Symphony Orchestra from 1963-1975. He conducted at Philharmonics in Buenos Aires, Lithuania, Madrid, Paris, and Stockholm, as well as operas in Bordeaux, Berlin, and Hamburg.

In an interview with the composer Wallace Cheatham, Lee spoke of being denied auditions with major American orchestras. “I then made up my mind that if I can’t join you, then I will lead you. I did make good on that promise to myself. Those two orchestras that denied me even an audition, I have conducted.”

Lee, at 60 years old, also fulfilled his dream of conducting the New York City Philharmonic. On January 15, 1976, Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday, Lee took to the conductor stand. The concert included Sibelius’s Violin Concerto, Rachmanioff’s Third Symphony. Most notably the concert included Kosbro, short for “Keep on Steppin’, Brothers”, by African American composer David Baker. Lee’s debut received a positive review in the New York Times for his conducting of “a fine concert”.

In honor of his years of dedication to sharing his musical talent, the City of Wheeling proclaimed August 31, 2017 “Everett Lee Day.” This coincided with Lee’s 101st birthday. In 2019 he was inducted to the Wheeling Hall of Fame. He passed in 2022, in a hospital near his home in Malmo, Sweden. He was 105. While Wheeling was just a short chapter in Lee’s incredible life journey, it comes as no surprise that his love for music and the arts was first nurtured in none other than The Friendly City.

References

Allen, David. “Everett Lee, Who Broke Color Barriers on the Conductor’s Podium, Dies at 105.” New York Times, 25 Jan. 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/20/arts/music/everett-lee-dead.html.

Cheatham, Wallace. Dialogues on Opera and the African-American Experience. Scarecrow Press, 1997, p. 27.

Grove, Rashad. “Everett Lee, the First Black Conductor on Broadway, Passes Away at 105.” EBONY, https://www.facebook.com/ebonymag/, 22 Jan. 2022, https://www.ebony.com/everett-lee-obituary/.

Oja, Carol J. “Everett Lee and the Racial Politics of Orchestral Conducting.” Home | Brooklyn College, 2013, http://www.brooklyn.cuny.edu/web/academics/centers/hitchcock/publications/amr/v43-1/oja.php.

“Wheeling Hall of Fame: Everett Lee > History | Ohio County Public Library | Ohio County Public Library | Wheeling West Virginia | Ohio County WV | Wheeling WV History |.” Ohio County Public Library | Ohio County Public Library | Wheeling West Virginia | Ohio County WV | Wheeling WV History |, https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/history/wheeling-hall-of-fame-everett-lee/7420#:~:text=Born%20in%20Wheeling%20on%20August,grand%20opera%20in%20this%20country. Accessed 15 Feb. 2024.