Note: This is a fictional tale. Rich Knoblich, WV storyteller and a regular winner of the Liar Contest at the annual Vandalia Gathering hosted by the WV Dept. of Arts and Culture, likes to add some drama, mystery and fun to his fables. It’s been said that some of the best lies are ones that are weaved with a thread of truth, which is exactly how Knoblich designs his short stories. Can you spot the truth in this tale?

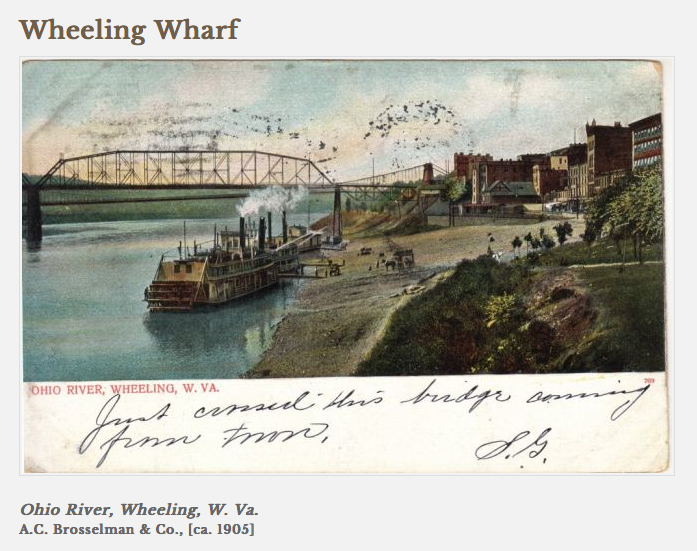

On a misty Wheeling waterfront one may perceive a vague image of a horse drawn wagon piled with kegs. The driver is hunched over, his hat settled down to his collar, while the smell of powder permeates the air. It has been over 160 years since 29 kegs of gunpowder exploded on Water Street along Wheeling’s wharf. Yet, in an evening twilight, one can sense the creak of a dray being pulled slowly by a team of horses. The driver, sweaty from loading the heavy kegs, is as worn as the draft horses. He guides his team up the sloping ground to the street. It is the apparition of Wallaston Kimberly, hired to haul kegs of rock powder to a site fourteen miles outside of Wheeling, VA. He did not complete the job.

By 1852, the completed Baltimore and Ohio Railroad line had reached Wheeling. Competing railroad lines needed a vital component to get their construction done – blasting powder [Alfred Nobel didn’t patent dynamite until 1867]. Railroad contractor Bryant and Bishop Co. had ordered 50 kegs of rock powder from a supplier in Cleveland. Brayton Walworth & Co. made a quality product and shipped the order down the Ohio River from the town of Beaver. Mr. A.C. Bryant sent a telegraph on Friday inquiring when the shipment, ordered 10 days before, would be delivered. He received the confirmation telegraph early Sunday morning. Bryant hired Mr. Wallaston Kimberly, a respected hard working drayman who owned his draft team, to haul the kegs from the wharf out to the worksite.

The Ohio River ran low in late August with a mud flat created from the seasonal rise and fall of freshets. The flat stretched from Water Street down to the steamboat landing. Wooden planks were laid on the gentle incline to walk upon or to roll kegs of merchandise for loading onto a steamboat’s lower deck.

On Monday morning Kimberly drove his dray upon the packed mud to the steamboat. After loading 29 kegs he gave a slap of the reins to the horses’ flanks and started up the wharf’s slope to Water Street. Lifting heavy powder kegs works up an appetite. Approaching 1:30 in the afternoon, Kimberly was anxious for lunch.

Drivers would normally guide their teams along Water Street turning east onto the Wheeling streets and National Road. But before Kimberly delivered the dray’s merchandise, the wagon man planned on taking a break at one of the beer halls to quench his thirst and allow the horses to rest before completing his route.

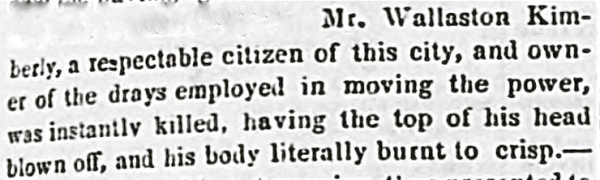

At 1:30, on the afternoon of August 29, 1853, Wallaston Kimberly maneuvered his dray onto Water Street loaded with 29 kegs of quality gunpowder owned by the railroad contractor. Then, literally, in a flash, Wallaston Kimberly was gone. Inexplicably, the entire load exploded, blowing off Mr. Kimberly’s head and injuring another drayman by the name of P. Schanley. Mr. Schanley was blinded and thrown into the Ohio River. The explosion shook buildings and blasted out the glass windows of several businesses in the downtown Wheeling area. The sternwheeler Orion, built in Wheeling, VA, in 1851 and the steamer Salem along with a wharf boat belonging to S.C. Baker & Co., were heavily damaged. Unlike many steamboats destroyed by boiler explosions, the harm to the steamboats came from undelivered kegs of powder. Fortunately, the blast went over the lower decks since the dray sat on an elevated street above the river.

Startled patrons at local brew pubs were knocked off of their barstools by the blast. Flying glass from shattered windows cut many individuals. Uninjured people rushed to the waterfront to witness the catastrophic scene and render aid. Everybody speculated as to what had happened.

Possible theories developed years later might apply to this incident. A gunpowder explosion occurred in nearby Pittsburgh on September 17, 1862. The Allegheny Arsenal on the north side of Pittsburgh saw three buildings destroyed in sequential explosions. Investigators of the Allegheny Arsenal disaster conjectured that loose powder keg lids allowed gunpowder to spill onto the roadway or spilt powder from factory floors was swept out through the doorways into the street. The cobblestones contained flint. Maybe an iron hoop around a wagon wheel or a metal horseshoe striking the cobbles created a spark. This would ignite loose powder on the ground. The explosion quickly spread to other areas. Perhaps a similar scenario of misfortune explains the Wallaston Kimberly disaster in Wheeling.

[Another unique theory has developed in recent times. Ladies wore long crinoline (hooped) skirts while working at the factory. The nature of the garment’s material may have caused a static spark igniting the powder on the ground.]

In the aftermath of the Wheeling incident a Coroners Jury strongly suggested “more stringent regulations in relation to the importation of gunpowder into the city – and of having such regulations rigidly enforced.” Newspapers at the time reported other incidents of powder kegs exploding through misuse or carelessness. The City of Wheeling took measures 28 years later to ensure the safety of people and property.

On April 22, 1881 the ‘Gunpowder and Blasting or Mining Powder’ ordinance became ordained by the Council of the City of Wheeling. Enacted just shy of the 100 year anniversary of Elizabeth Zane’s 1782 gunpowder run saving Fort Henry, the ordinance’s numerous provisions required:

SEC. 2 Gunpowder, mining or blasting powder had to be stored in copper, tin or sheet-iron containers. Merchants could keep twenty-five pounds of powder but it must be within ten feet of the entrance. Signage over the entrance must state “Licensed to Sell Gunpowder.”

SEC. 3 Only a single keg could be transported through the streets and the tight secure keg must be covered with incombustible cloth painted with the word “Powder.” The powder shall be in transit through the streets for no more than one hour. No dealer shall buy, sell or remove powder within the city after sunset or before sunrise.

SEC. 4 Vehicles used to transport powder must be kept more than 300 feet apart.

For those unfamiliar with the local tavern folklore, “To Wallaston!” goes the cheer as Wheelingites raise their glasses to honor the nearly forgotten drayman’s spirit at Heritage Port. Hoisting a cold brew to acknowledge the working man’s phantom is a symbolic gesture to ward off a reoccurrence of the event that caused Wallaston Kimberly’s hapless demise. The odd local custom is rooted in Wheeling’s past. The ritual, performed where his unexpected death happened at Wheeling’s former wharf or in bars, keeps death at bay. So raise your glass in recognition of a regular guy and join in the toast “To Wallaston” who blew up above the wharf in Wheeling, VA.