This was life on Piedmont Lake, and 40 years later, not much has changed. The cabin is still there, and now my kids spend summer weekends at the lake. Likewise, so many Ohio Valley residents slip off to Tappan, Clendening or Seneca on weekends. The lakes offer us a recreational opportunity quieter than the Ohio River, more peaceful than the creeks.

So how did it come to pass that we should be so blessed with beautiful lakes in the middle of Ohio farm country? It’s a story that starts with violent winds.

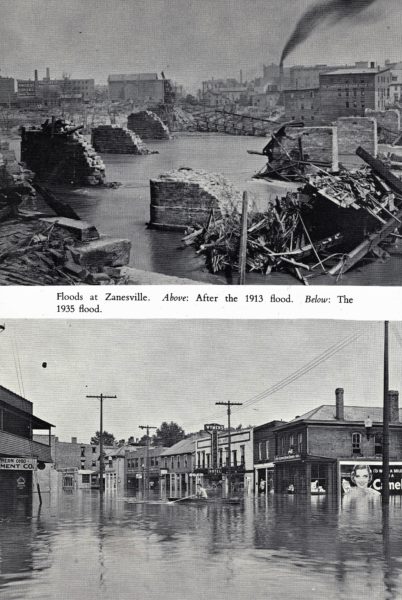

THE GREAT FLOOD OF 1913

It began with a storm front in March of 1913. Tornadoes sucked two babies out of an Omaha orphanage and killed 30 people when a movie house collapsed. They sent a naked man hurtling through a dining room window, where he landed in front of a family at their meal and asked for a pair of trousers. Bodies fell from the sky. Two hundred people died in twisters that spanned the Midwest from Nebraska to Indiana.

When the storms reached Ohio, they brought with them a torrent of rain. It rained from March 23 to March 27, and as the water rose, the Ohio River and its tributaries swallowed cities like Fort Wayne, Indianapolis, Cincinnati and Columbus, among many others. The flood swept houses from foundations with residents still inside. People drowned. People froze to death. One woman climbed a telephone pole and crossed the wires with her baby in a bag on her back as the water came up. Gas lines ignited, and fires raged as the frigid surge swept by at 60 miles per hour. It was a disaster of epic proportions. More than 1,000 people died, over 20,000 homes washed away, and the damage topped today’s equivalent of $5 billion. Not a living soul had ever seen anything like it.

No city was hit harder than Dayton. The Miami River swallowed the downtown under 20 feet of water. When the flood finally receded, dead horses and sunken Model T Fords littered the streets. And though the water withdrew, it had to go somewhere, and cities along the Mississippi continued to experience flooding for two months.

You can read the story of the Great Flood in Geoff Williams’s book, Washed Away: How the Great Flood of 1913, America’s Most Widespread Natural Disaster, Terrorized a Nation and Changed It Forever. That flood continues to influence our lives today. Any time we reel in a bass or hop in a kayak at Piedmont Lake (or Atwood or Leesville …), we owe it to the Great Flood of 1913.

NEVER AGAIN

The citizens of Dayton were determined that such a nightmare should never happen again. They pledged money for a flood control study and hired Arthur Earnest Morgan, a civil engineer who would later become the first chair of the Tennessee Valley Authority. The study looked at the flooding and what could be done about it.

Morgan and his firm ultimately recommended a watershed flood-control project. He believed a series of reservoirs could store and release floodwaters using a “dry dam method.” A dry dam is intended to let water flow freely under normal conditions. During intense rainfall, however, the spillway closes to retain floodwaters. The lake swells and the excess water releases in a slow, controlled manner over a period of time, thereby preventing communities downstream from being inundated.

No such project had ever been conceived. Indeed, it was believed impossible by other engineers. Moreover, who would oversee its operation upon completion? The federal government? The state of Ohio? What the region needed was an independent body capable of managing these reservoirs and dams across city and county boundaries, but the law didn’t allow for it. It would ultimately take some legislation to move forward. The Ohio legislature got to work and passed the Conservancy Act of Ohio, which provided for the creation of this regional agency. Thus, the Miami Conservancy District was born, ready to tackle the flooding problem.

Morgan’s Miami River project came to fruition with the construction of his recommended reservoirs. As he predicted, floods came and went without incident. The system was put to its first true test in 1937 when the region received the same amount of rainfall that had fallen in 1913. It rained for 12 days rather than five, but less than 15 percent of the storage space in the reservoirs was used. Morgan’s system worked.

BUT ZANESVILLE IS UNDERWATER, TOO

Across the state, the people who lived along the Muskingum River and its tributaries sought flood-control solutions of their own after the Great Flood, with no success. What’s more, the region had an ongoing problem with erosion due to water mismanagement. In 1928, the citizens of Zanesville followed the example of their Daytonian brethren and commissioned a flood study by Morgan.

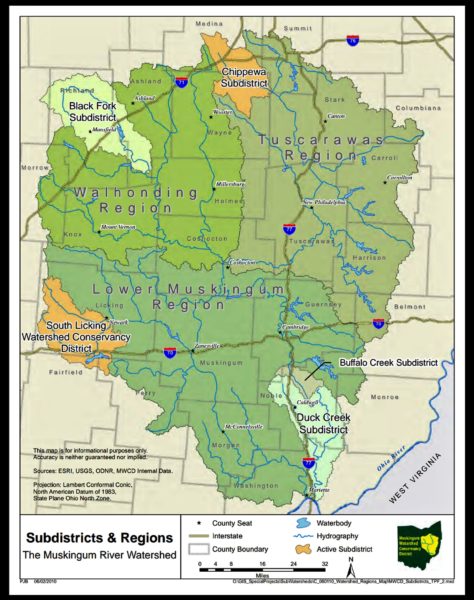

The Muskingum River is part of Ohio’s largest drainage system. The watershed touches 27 counties and over 8,000 square miles. Morgan’s study revealed problems the Miami watershed hadn’t faced: it was neither as feasible nor as cheap to work within the Muskingum watershed. The drainage area was bigger, development crept right up to the banks of the river and its tributaries, and the area was crisscrossed by railways. To further complicate things, the towns within the watershed had their own agendas for water management. Canton and Akron prioritized water conservation for industrial use; Zanesville and towns along the Muskingum River worried most about flood control; Dover and New Philadelphia sought improved river navigation. The major communities in the watershed were far apart, and local plans didn’t protect everyone in the region. Morgan told the cities of Massillon, Newcomerstown and Zanesville to expect flooding 25 percent greater than the 1913 flood in the near future.

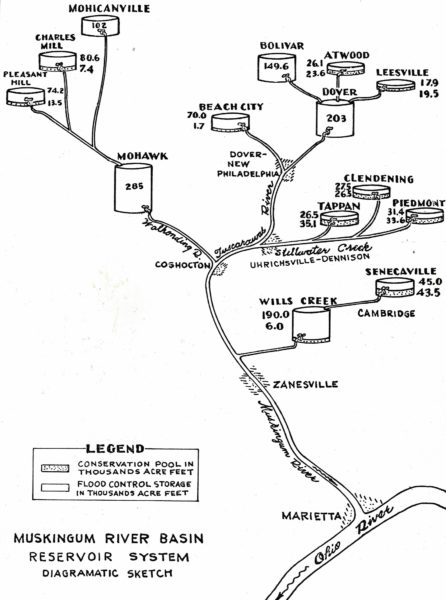

Zanesville, like Dayton, needed a conservancy district with the authority to control water management practices. Interest in a conservancy began to grow, despite the onset of the Great Depression, and on June 3, 1933, the Muskingum Watershed Conservancy District was established. Morgan and his engineers took into consideration all the obstacles the watershed faced. Ultimately, they recommended 15 dams and reservoirs, most of which would have permanent lakes or “conservation pools.” Additionally, Morgan suggested improvements such as widening channels, correcting sharp bends in the rivers and building levees to add to the flood-control efforts.

In his 1976 book, A Valley Renewed: The History of the Muskingum Watershed Conservancy District, author Hal Jenkins describes the plan for lakes on the Tuscarawas River, a tributary of the Muskingum on the east side of the watershed:

“Stillwater Creek, another tributary of the Tuscarawas, would have four reservoirs: Tappan on Little Stillwater, Clendening on Brushy Fork, Piedmont on Stillwater and Freeport on Skull Fork. The remaining large tributary of the Muskingum above Zanesville, Wills Creek, would be controlled by two reservoirs: Wills Creek, the key reservoir a few miles above its mouth, and Senecaville on Seneca Fork southeast of Cambridge.”

All 15 of the planned reservoirs except for Mohawk would have conservation pools, the smallest being Beach City (220 acres) and the largest at Senecaville (3,550 acres). At maximum flood elevation, the reservoirs would swell to roughly 76,000 acres. At this level, the floodwaters of 1913 would have taken up only 65 percent of the capacity. Total storage would be 1.6 million acre-feet, of which 1.35 million acre-feet would be reserved for flood control and 250,000 acre-feet for water conservation. (An acre-foot is the volume of a sheet of water one acre in area and one foot deep.) Fourteen dams and reservoirs were ultimately constructed, and 10 of those were also designed for water conservation and recreation. These are the lakes we know and love today: Atwood, Beach City, Charles Mill, Clendening, Leesville, Piedmont, Pleasant Hill, Seneca, Tappan and Wills Creek. The estimated cost was $33 million; $21 million would come from the federal government, and $3 million would come from the state of Ohio.

GET OFF MY LAWN, MWCD

So the lakes filled up and then everyone went out and bought a pontoon boat, right? Nope. Not even close. All those reservoirs and their projected flood capacity took up a lot of land, and all that acreage belonged to landowners. Eight thousand properties would be damaged. A team of appraisers worked full-time for several years to assess and value the land MWCD needed.

While the majority of landowners sold to the District, many fought it. In total, 7,300 people filed exceptions for properties of all types, including residential, commercial, agricultural, railroad, and public utility companies. In Freeport, the future site of Piedmont Lake, a group of land speculators got together and cornered the land market, demanding exorbitant prices. In response, the MWCD reformed the plan to exclude Piedmont and instead construct a reservoir at Bolivar and one on the River Styx near Rittman, Ohio. That changed the tune in Freeport. A general outcry arose all over Harrison County and, luckily for so many of us, plans for Piedmont Lake went forward.

In some cases, more than just farmland disappeared beneath the waters. Highways had to be moved — no easy task, but still not as troublesome as entire neighborhoods that stood in the way of progress. In A Valley Renewed, Jenkins recalls the fate of the tiny town of Tappan:

“A protest from 136 residents of the Little Stillwater Valley stated that the Tappan reservoir would destroy or seriously impair the usefulness of 6,000 acres of land and cited a long list of objections including the following:

‘(1) it will destroy the village of Tappan, which has 46 residences, 1 new school house, 3 churches, garages, work shops and other buildings; (2) it will mean the destruction of 5 school buildings located in the Stillwater Valley…; (3) it will mean the destruction of 6 local churches and will submerge the cemeteries that live near them; (4) it would lead to the destruction of 10 miles of United States highway known as Route No. 250 and Route No. 36. …’”

Ultimately, plans for the dam and lake proceeded. The residents of Tappan’s 50 homes abandoned the town, the school and the churches, which soon disappeared forever. The cemetery was moved to the north end of the lake, but it’s not known if all of the graves were moved. Similarly, the town of Laceyville, Ohio, was also destined to drown with the damming of Little Stillwater Creek.

WHO’S IN CHARGE, HERE?

Managing the lakes is a task divided up between several agencies. The MWCD oversees the reservoirs, while the Army Corps of Engineers runs the dams and spillways. (It’s interesting to note that, early on, the Corps thought the lakes were unnecessary and tried, unsuccessfully, to talk MWCD into draining them.) In turn, the Corps of Engineers knew they couldn’t manage recreation, so the District leased the hunting and fishing rights to the Ohio Division of Conservation and Natural Resources. Today, the Ohio Division of Natural Resources (ODNR) is responsible for fish and wildlife management on MWCD lakes and lands.

Although the primary goal of the MWCD was never recreation, District officials always knew it would play a vibrant role in the life of the reservoirs. The lakes are dotted with education and church camps. Marinas and boat clubs hum with summer activity, and the Ohio Huskie Muskie Club continues to accrue new members each year. (Piedmont has boasted the state muskie record since 1972 when Mr. Joe D. Lykins hauled in a 50.25-inch, 55.13-pound monster.)

THE HAPPIEST OF PLACES

Seneca and Piedmont Lake both reached conservation pool-level in March of 1942. Within a decade, my grandparents would plop my dad and uncle in a rowboat at the marina for their first Piedmont experience. A few years later, my grandfather would rent a boat with a motor, and the boys would putter to other coves. By the time I came along in the late 1970s, we’d cruise Piedmont in a red pontoon. My dad took me for winter hikes on the ice in the 1980s; my husband joined the Ohio Huskie Muskie Club in 2004 with his very big fish. I can remember boat rides with our new babies and each child’s first fishing pole. Now, we watch them paddle off on their own kayaks. Family continues at the lake.

Like so many in the Ohio Valley, the waters of the Muskingum Watershed Conservancy District have become a second home. It’s where I received my nature education, where I learned about trilliums and beech trees and water snakes. I’ve seen the lake rise and fall, seen it overflow with floodwater and crinkle our poor dock like an accordion. During the flood of 2004, the lake came well up into the woods. It was messy, but thanks to a group of forward-thinking people over a century ago, every time Piedmont rises out of its banks, someone downstream is spared.

• Laura Jackson Roberts is a freelance writer in Wheeling, W.Va. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Chatham University and writes about nature and the environment. Her work has recently appeared in Brain, Child Magazine, Vandaleer, Animal, Matador Network, Defenestration, The Higgs Weldon and the Erma Bombeck humor site. Laura is the Northern Panhandle representative for West Virginia Writers, a blog editor for Literary Mama Magazine and a member of Ohio Valley Writers. She recently finished her first book of humor. Laura lives in Wheeling with her husband and their sons. Visit her online at www.laurajacksonroberts.com.