Editor’s Note: This fall, an Honors College writing course at West Liberty University, taught by Dr. Steve Criniti, adopted the City of Wheeling as the course focus. The course, entitled “Writing Wheeling,” included a series of projects designed to explore Wheeling’s past, present, and future. This article was originally created as an assignment for the course.

On September 2, 1908, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B & O) opened a new passenger station in Wheeling. The Wheeling Intelligencer hailed it as the “B. & O’s Magnificent Present to Wheeling.” Fifty years later, the last passenger train left the station. The year after, the station was sold to investors, and Wheeling’s magnificent present sank into obscurity. In 1975, the one-time passenger station was chosen to house the West Virginia Northern Community College, and that is what it still is today. The B & O passenger station, with its auspicious beginning and downward slide, encapsulates Wheeling’s changes and its decline.

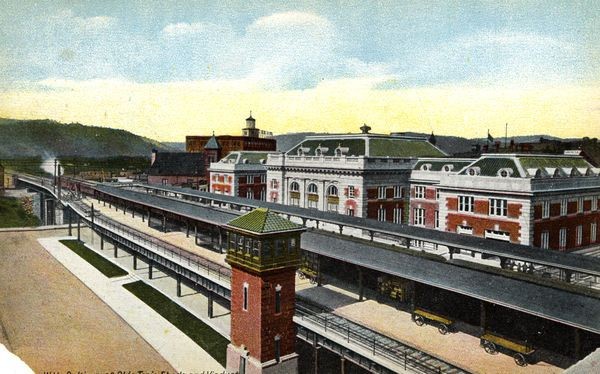

It is vital to understand what a momentous thing the passenger station really was. Its neo-Roman architectural style—imported from France and officially called Ecole des Beaux-Arts—was, in its era, the popular style for monumental buildings. The company spent two years building it, and more than 300,000 dollars (roughly equivalent to seven and a half million dollars in today’s money). At its opening in 1908, The Wheeling Intelligencer praised the new station as “a marvel of beauty” and called it “the most modern and the most expensive station ever constructed” by the B & O in its eighty-year existence. The newspaper carefully noted, “The company, of course has larger stations in some of the larger cities, but none so elaborate and expensive as it now presents to Wheeling.” The B & O passenger station was far more than utilitarian. It was, indeed, a monumental building, but a monument to what?

The 1908 passenger station was built for two reasons, history and prosperity, and it was emblematic of both. Wheeling had been central to the B & O Railroad at its beginning. The B & O was America’s first railroad, founded for the express purpose of reviving Baltimore’s economy by connecting the city to the Ohio River. Wheeling was made the railroad’s western terminus, beating out Pittsburgh, and the railroad finally reached the city on Christmas Eve 1852. Shortly afterward, The Wheeling Intelligencer called the completed railroad “one of the greatest works of the age,” and this was not as grandiose as it now sounds. It is no longer apparent to us, 160 years later, but the railroad from Baltimore to Wheeling was an historic accomplishment. “An unbroken link” between the Chesapeake and the Ohio River was revolutionary in 1850, and building a railroad across the Alleghenies pushed the boundaries of the possible in engineering.

As compelling as this history is, the prosperity that followed was an even greater reason for the building of the new passenger station. Wheeling’s industries and its position as a transportation hub put its railroads to good and profitable use. Freight trains shipped the city’s manufactured goods to market, and at the time B & O began to build its new passenger station, one hundred passenger cars ran in and out of the city every day. The 1908 passenger station was built from Wheeling’s present prosperity and the successes of the previous fifty-five years.

It would be hard to find any one building that so perfectly represented Wheeling’s achievements and aspirations as the B & O passenger station in 1908. As Wheeling had first won the railroad away from Pittsburgh, so it could favorably compare its new station to the stations of larger cities. The old ambition for a place among America’s great cities was alive and finding expression in the station. The means of pursuing that ambition could be found there, too. Wheeling’s rise to prominence had been inextricably linked to its position as an access point to the west and to the river, and the railroads had become heir to the traffic that once passed through the National Road and the Ohio River. The products of the city’s industries—the source of its wealth—were freighted on the railroads, and every day people streamed through the passenger station into Wheeling. Industry, importance, money, bustling activity, pride: All were contained in the magnificent B & O passenger station.

The station was also a statement of hope, a hefty investment in the future. The company expected it to be worth their money, and for some decades that expectation was fulfilled. But in time the railroad industry—like other industries Wheeling had made so much of, and depended so much on—went into slow and irreversible decline. Finally B & O cut off passenger service to Wheeling, and in 1961 the last passenger train left the B & O station. Less than a year later, the station was sold and then largely forgotten.

The building received a revival of sorts in 1975, when it was purchased for the West Virginia Northern Community College and its exterior was restored according to its original design. The interior, however, was remodeled out of its original purpose and, no doubt, out of much of its original elegance. The large waiting room, two stories high, was converted into two floors, and lowered ceilings and new partition walls further cut down the building. The walls were covered with vinyl-clad drywall, and the floors with new carpet and tile. Once The Wheeling Intelligencer found the interior of the B & O passenger station “exceptionally prepossessing.” It seems unlikely that anyone will ever say the same for the interior of the West Virginia Northern Community College.

The conversion of a railroad station into a community college reflects Wheeling’s shift away from industry and transport to a ‘soft’ economy. Just as importantly, it is an early example of adaptive reuse in Wheeling. In recent years, adaptive reuse—the adaption of an old building from its original function to a new one—has become important in Wheeling. It is touted as both a method of preserving the city’s history and culture and as a method of boosting the city’s economy. Certainly it helped preserve the B & O passenger station from deterioration and even razing, and no doubt the community college brought people and jobs into Wheeling. So if the B & O station was a proud symbol of the old Wheeling, perhaps the community college is a hopeful sign for the new Wheeling.

Some might even argue that a college, as a place of learning, is better than a railroad station, a place of travel and business. But that puts the question too abstractly. What matters is not whether, in theory, a railroad station is better than a college, but whether, in practical reality, the B & O passenger station was better than the West Virginia Northern Community College. The B & O station played an integral role in sustaining the traffic, both of goods and of people, that was Wheeling’s lifeblood for so long. Built magnificently, and at considerable cost, the station marked a time when the city had not only a past worth commemorating but a future worth that kind of investment. Like the railroad it was built for, the station was in its day at the forefront of modernity, and now—when Wheeling seems so hopelessly left behind by the times—its loss is a poignantly symbolic thing.

By contrast, the community college neither fuels the city’s economy nor brings pride to the community in the same measure that the old passenger station once did. One of the college’s greatest distinctions is that it is a noteworthy example of adaptive reuse. Yet even that sharply illustrates the decline from the Wheeling of a hundred years ago to the Wheeling of today, and the decline from the B & O passenger station to the community college. It is, after all, an unmistakable decline when a city goes from creating great buildings to preserving them.

Photos Courtesy of Wikipedia and Historic Wheeling Wikispaces