Seventy-one years ago, on April 14, 1948, the last streetcar of Wheeling made its final trip—its last day overshadowed by historic flooding on the Ohio River.1 Even though Wheeling’s streetcars may have ended quietly, their impact on the development and history of Wheeling is nothing less than exceptional.

All Aboard!

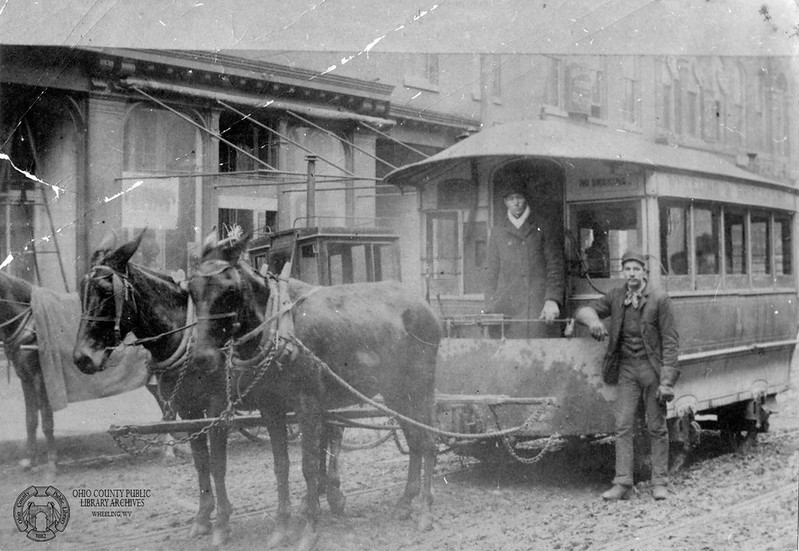

When most people hear “streetcar,” they think of small electric powered passenger trains on tracks running through the city streets, sometimes referred to as “trolleys.” However, the early predecessor to electric streetcars was actually horse-drawn. Chartered in 1863, when Wheeling was still part of Virginia, the Citizens’ Railway Company operated the horse-drawn cars.2 They still ran on tracks to create less resistance for the horse, but it was harder for them to go up and down the steep hills and they were limited by the horse’s energy.3

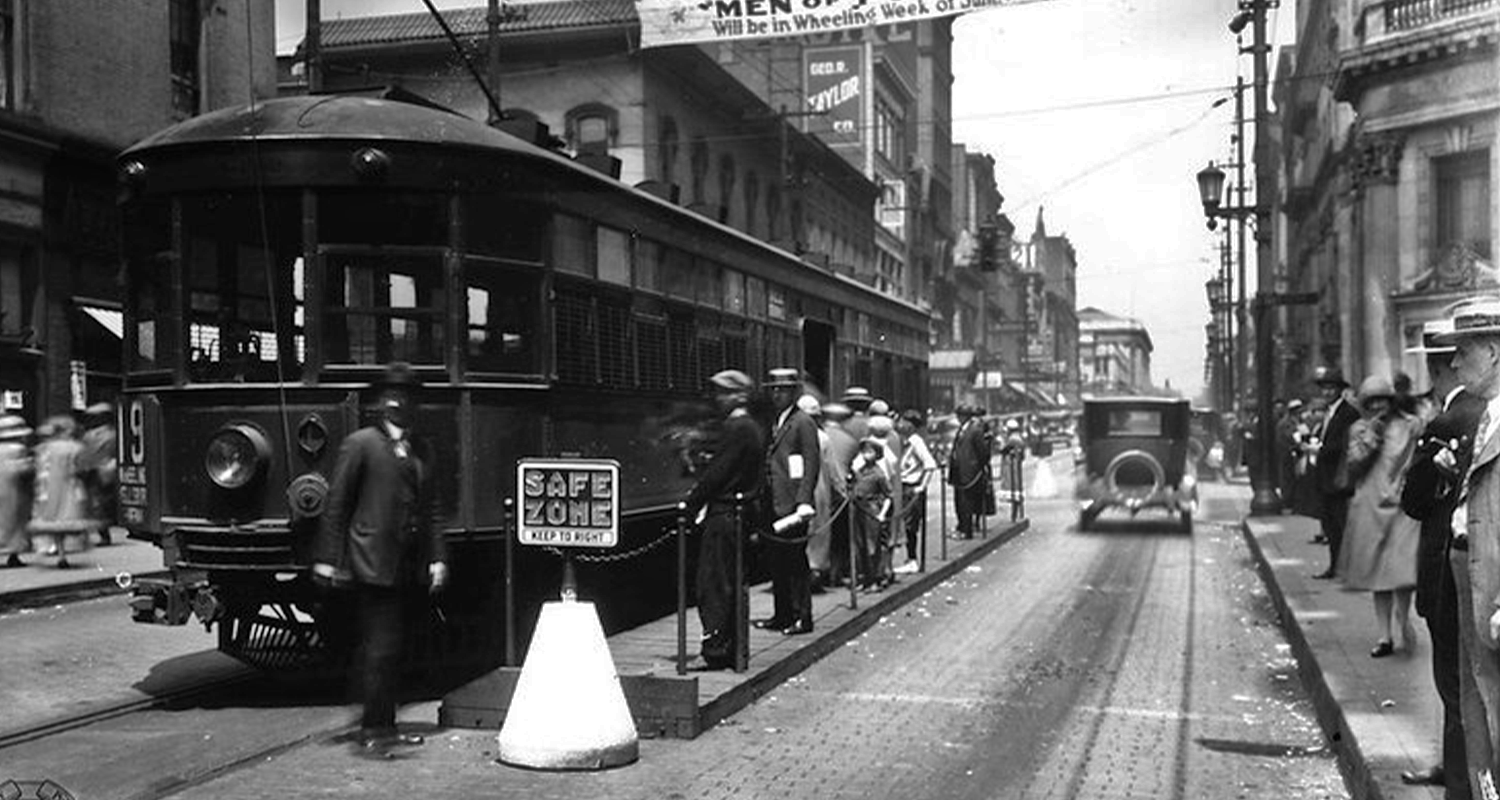

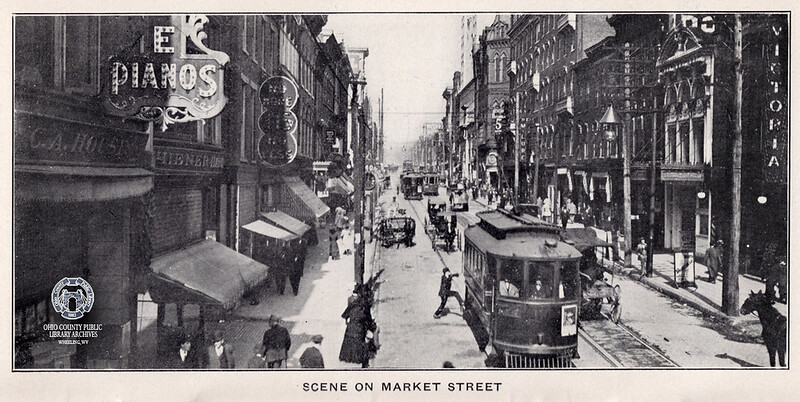

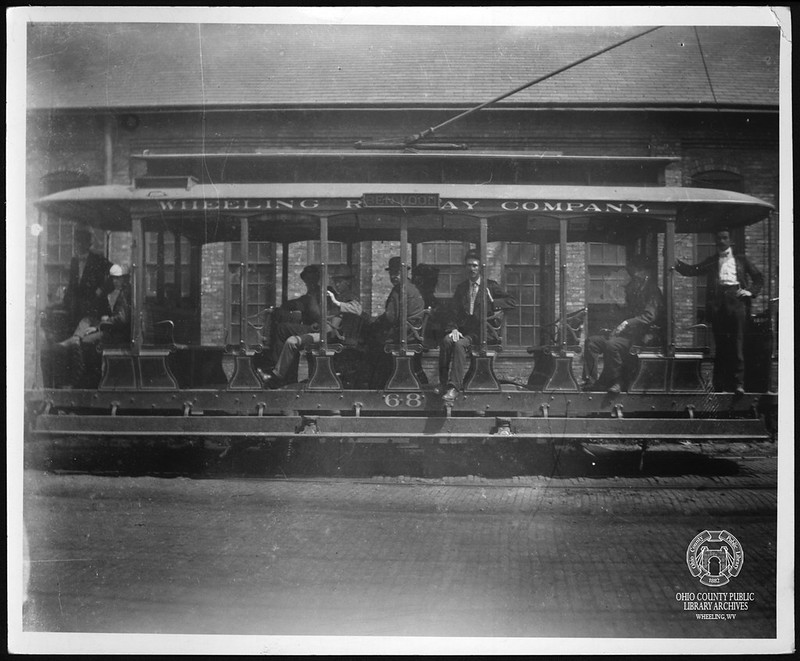

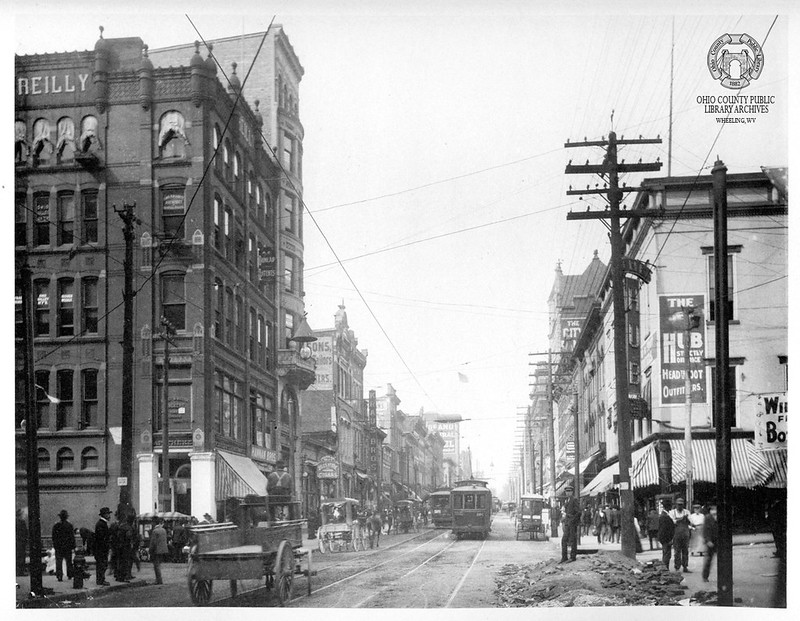

On March 15, 1888, the electric streetcars were introduced in Wheeling—the first day created quite a spectacle. Hundreds of people gathered to witness the trolley’s maiden voyage from the corner of Main and 27th Streets. According to the Wheeling Intelligencer, “everything worked remarkably smooth and satisfactorily for a first trip.”4

For the next six decades, the streetcar systems in Wheeling and surrounding areas were reorganized and run by numerous different companies. As the system expanded, different lines were connected and provided access to more of the area. Like other forms of public transportation, the streetcars provided a public good and transported all types of people all over Wheeling—from the youngest baby to the oldest resident. A 1921 pamphlet published by the Wheeling Public Service Co. and the City Railway Co., entitled Traction News, extolled the benefits of the streetcars, claiming that “the community must have the street car and the street car must have the community.”5

Streetcar Suburbs

Before the streetcar, most local people got around by foot or horse and wagon. As streetcars made it easier and quicker for people to get around, Wheeling residents could live further away from where they worked and shopped downtown. As was the case in many other cities with streetcar systems, this facilitated the formation of “streetcar suburbs.”6

In Wheeling, these neighborhoods became affectionately known as “Out-the-Pike.” While Wheeling Island was known as the fashionable turn-of-the-century location for wealthy residents to build their homes, the Out-the-Pike neighborhoods quickly started to contend. Driving down National Road, you can still see the evidence of stately homes with amenities such as carriage houses, which now contain modern cars or lawnmowers.

In general, the suburbs were cleaner; families didn’t have to worry as much about the smog and transmittable diseases. A 1907 description of the Edgwood neighborhood touts that “the town possesses many of the advantages of city life, with but few of its dangers; there are no saloons and no factories; pure air and pure water are abundant.”7

Significant events or occasions in Wheeling warranted special streetcar services, like increased frequency or after-hour operation. For example, when the visit of the famous evangelist Billy Sunday drew tens of thousands of people to Wheeling, the City Railway Company and the Wheeling Traction Company added special street car services to account for all the extra people.8 When the elegant Stratford Springs Hotel in Woodsdale held dances that lasted into the late evening, a special trolley was arranged to carry the tired dancers home.9

It wasn’t only the Wheeling area that benefited from the streetcars. By the 1890s, most of the surrounding towns up and down the Ohio River were connected via the streetcar system.10 Through a series of various systems that changed hands over the years, as far north as Wellsburg was connected to as far south as Moundsville—a distance of approximately 27 miles.11 The streetcars also crossed the Ohio River with routes onto Wheeling Island and into Ohio.

Tragic Accidents

Any form of transportation, whether it be cars, trains, buses, airplanes, or streetcars, there is always a low level of risk. Unfortunately, while rare, accidents do happen.

On October 28, 1926—after the streetcars had been in service in Wheeling for almost four decades—there was a fatal accident on the steep Mozart Hill. The brakes malfunctioned and the out-of-control trolley jumped the tracks and ended up crashing through the front room of the store of Leo Pack at around 6:25 in the morning. Twelve passengers in the streetcar were injured, while the only person killed was the motorman, Frank E. Eberlein. While the cause of the accident was never confirmed, the speculation at the time was that dead leaves on the tracks prevented the brakes from working correctly.12

Other accidents involving streetcars resulted in much fewer human fatalities or injuries. For example, in February 1918, the Island Car Barn—that housed some of the streetcars when they weren’t in service—burned, destroying 29 streetcars.13 Despite occasional accidents on busy streets, streetcars were generally considered just as safe as any other form of public transportation at the time.

The Decline of the Streetcar

While streetcars were very popular in many cities at the turn of the century and after WWI, the advent of new technology led to their demise. As personal automobiles became more accessible to the average American and buses proved less expensive to operate and build, the streetcar became overshadowed.14

In addition, between the 1930s and the 1950s, the National City Lines bought up a significant number of streetcar systems across the country. However, National City Lines was controlled by General Motors—one of the largest car manufacturers in the US—in addition to other corporations with interests in automotive services. Despite the perceived “Great American Streetcar Scandal,” historians and researchers have since pointed out that streetcars were on the decline before General Motors got involved.15

In 1933, in the middle of the Great Depression, Wheeling Traction Company employees banded together to buy the company, renaming it the Co-operative Transit Company.16 While still running streetcars, the Co-operative Transit Co. started prioritizing their investment in buses, eventually switching over entirely.17 While Wheeling’s streetcars lasted longer than most other cities (and were not bought by National City Lines), they were phased out a few years after WWII in 1947-1948.18

Public Transportation and Streetcars Today

While streetcars no longer run on the streets of Wheeling, they are making a comeback in other cities. Studies conducted in Seattle, Washington and Portland, Oregon showed a correlation between increased development and business along streetcar routes.19 Other cities, like San Francisco and New Orleans, capitalize on the nostalgic quality of vintage streetcars and use them to promote tourism.

Recently, as construction crews tore up the corner of Main and 16th Streets to replace water lines, they ran into the old trolley lines that had been paved over.20 Even though most of the streetcars themselves have disappeared (although one currently resides in a museum in Kennebunkport, Maine), the sociological and community change that they brought to Wheeling is still felt every day. You don’t have to dig long to uncover traces and remnants of Wheeling’s recent past.

Whether it be streetcars in the early 1900s or buses in the 2021, public transportation is crucial to a city’s health and the prosperity of its residents. For many people—from huge cities like New York City to small cities like Wheeling—public transportation is how they navigate their world—buying groceries, traveling to work, getting to the doctors’ office, and more. While the jury is still out on a streetcar renaissance, public transportation is always a relevant topic.

To learn more about streetcars in Wheeling, visit the Ohio County Public Library’s exhibit “Wheeling Through Time: The William J.B. Gwinn Transportation Collection, 1884-1960.” Most of the photos in this article come from the William J.B. Gwinn Transportation Collection in the OCPL Archives, for more information, click here.

• Emma Wiley, originally from Falls Church, Virginia, was a former AmeriCorps member with Wheeling Heritage. Emma has a B.A. in history from Vassar College and is passionate about connecting communities, history, and social justice.

References

1 William J. B. Gwinn, “Wheeling Traction Company,” Goldenseal Magazine, date unknown.

2 “Wheeling Traction Company,” in The History of West Virginia, Old and New, (The American Historical Society, Inc., 1923), accessed March 31, 2021, https://www.wvgenweb.org/ohio/whg-traction.htm.

3 “Wheeling Traction Company,” in The History of West Virginia, Old and New.; Gwinn, “Wheeling Traction Company.”

4 “The Electrical Railway,” Wheeling Intelligencer, March 16, 1888, p. 4.

5 Wheeling Public Service Co., City Railway Company, “Success of Car Lines Benefits All Persons,” Traction News, Vol. V, July 23, 1921, Ohio County Public Library Flickr, accessed April 1, 2021, https://www.flickr.com/photos/ohiocountypubliclibrary/5568457365/.

6 “The Trolley and Daily Life,” National Museum of American History, accessed April 1, 2021, https://americanhistory.si.edu/america-on-the-move/streetcar-city.

7 “History of Edgewood Graded School,” in The History of Education in West Virginia, (Charleston, WV: Tribune Printing, 1907): 181-182, Ohio County Public Library, accessed April 1, 2021, https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/history/history-of-edgewood-graded-school/4060.

8 “Sunday Will Arrive Today,” Wheeling Intelligencer, February 17, 1912, p.6.

9 Daniel L. Cusick, “Many Recall Plush “Stratford Springs,”” Wheeling News-Register, Ohio County Public Library, accessed April 1, 2021, https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/history/recollections-of-stratford-springs/3391.

10 Gwinn, “Wheeling Traction Company.”

11 “Wheeling Traction Company,” in The History of West Virginia, Old and New.

12 “House Stops Runaway Trolley,” The Wheeling Register, October 29, 1926, Ohio County Public Library, accessed March 31, 2021, https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/history/5211.

13 Gwinn, “Wheeling Traction Company.”

14 Mark Henricks, “The GM Trolley Conspiracy: What Really Happened,” CBS News, September 2, 2010, accessed April 8, 2021, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/the-gm-trolley-conspiracy-what-really-happened/.

15 Eric Jaffe, “Be Careful How You Refer to the So-Called ‘Great American Streetcar Scandal,’” Bloomberg CityLab, June 3, 2013, accessed April 8, 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-06-03/be-careful-how-you-refer-to-the-so-called-great-american-streetcar-scandal.

16 Borgon Tanner, “Streetcar Lines,” e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia, May 29, 2020, April 1, 2021, https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/612.

17 “An Important Announcement to the General Public,” The Wheeling Intelligencer, September 11, 1947, p. 19.

18 James D. Schantz and Frederick J. Maloney, “Car #639: Wheeling’s Last Trolley,” People’s University, Ohio County Public Library, January 7, 2021, accessed April 1, 2021, https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/programs/people-university-livestream-wheelings-last-street-car/7391.

19 Jeffrey Brown and Joel Mendez, “The Streetcar Comeback and Its Development Effects,” Mineta Transportation Institute at San Jose State University, November 19, 2018, accessed April 7, 2021, https://transweb.sjsu.edu/press/Streetcar-Comeback-and-Its-Development-Effects.

20 Scott McCloskey, “Unearthing Remnants of Wheeling’s History,” The Intelligencer Wheeling News-Register, March 25, 2021, accessed April 7, 2021, https://www.theintelligencer.net/news/top-headlines/2021/03/unearthing-remnants-of-wheelings-history/.