(Editor’s Note: This introduction is the third entry of a series of stories that will focus on the history of the game of baseball in the Wheeling area.)

“Belle Isle was Yankee Stadium”

There were three steps down into the dugout. A real dugout.

Just like the big leagues. Just like we saw on television or when our fathers took us to Forbes Field or another venue that possessed that real feel.

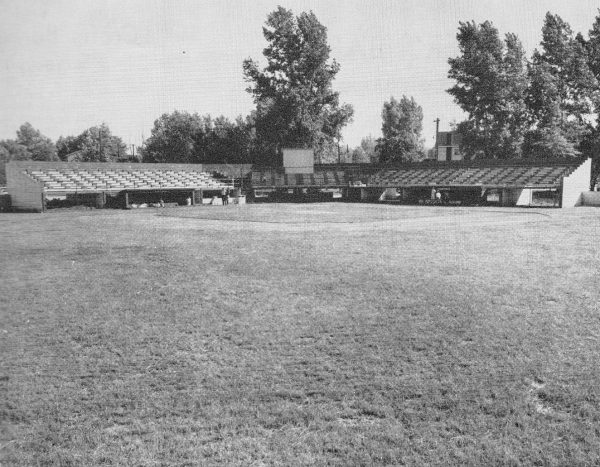

Belle Isle Ballpark, on the most northern tip of Wheeling Island, once was a monument to the game for little boys in the Upper Ohio Valley from the early 1950s until the early 1990s.

That’s when it was pulverized to the ground, and the concrete stands were replaced by aluminum bleachers, the dugouts filled in for a plank of a bench, and the wow-factor vanished for parents and players alike.

“City Hall does this, and they do that, and whatever, but I think the worst decision those people have ever made was taking down that ballpark,” said Dan Taylor, a lifelong resident of Wheeling Island who coached Little League teams for more than 40 years. “I cried while I watched them tear that stadium down, and I didn’t stay the whole time because I couldn’t. Just seeing it going away pissed me off so much I had to walk away, and I don’t even look at it now.”

There were two ramped entrances, a concession stand in the middle, a press box where radio broadcasters and statisticians were employed, and enough room for a couple of hundred spectators. For several decades, Belle Isle Ballpark was a showcase where every team wanted to play and was packed throughout the spring and summer months.

“It was a stadium. It wasn’t just a ballfield somewhere. It was a stadium,” said Buck Porter, a member of North Wheeling teams until the organization folded when he was a pre-teen. “It wasn’t a big place, but it was still a stadium for us kids. It literally made you feel like one of those old-time baseball players we always heard about. It made us feel like we were a professional player. It allowed us to dream of making it while a lot of the other fields were, just dusty sandlots.

“But Belle Isle? I remember always being in awe of that stadium. We didn’t like playing the Island teams because they were always so good, but playing at Belle Isle was something you couldn’t help but look forward to,” he continued. “Belle Isle was not a sandlot. It was a true ballpark, and the dugouts were just like the major leagues with the steps going down. Belle Isle was Yankee Stadium. Even for this North Wheeling kid, Belle Isle Ballpark is something I’ll never forget.”

185-225-190

The home team’s dugout was on the left side of Belle Isle Ballpark, and the visitors were assigned the dugout on the right side.

“That was so the sun would shine right into their eyes,” said Taylor, a coach for Wheeling Island for more than 40 years. “We made those teams sit in the sun while our teams got to be in the shade because that’s what you did back then to gain any kind of edge you could. It’s part of home-field advantage.

“Of course, that was also the time when most kids were out in the sun all day, so who knows what kind of impact that even had?” he continued. “What I do remember from coaching there was that the dugouts weren’t tall enough for me when I would jump up because of something that happened on the field. Too often I would catch that little button on the top of my ballcap, and that hurt like hell when that happened.”

Taylor’s coaching career began at Belle Isle Ballpark at a time when the facility hosted the Wheeling Midget League. His father was the head coach of Junior team and after “cut day,” he decided to start a farm league with four teams, the Pirates, Braves, Cubs, and Cardinals.

“And we played each team seven times so we could have a 21-game schedule,” he said. “All the coaches were in high school, and our teams got good. We played against my dad’s team the second year and we beat them. That was a tough night at home; I know that.

“But I can tell you we didn’t realize what we had back in those days, but the older I got, the more I appreciated that place. That’s when I realized the experience those kids were getting from playing at Belle Isle, and that’s why it made me so damn mad to see it come down. I can remember very well that Donnie Dusick stood up there when they started it, and we had tears in our eyes,” Taylor said. “I did grab a couple of the concrete blocks because I wanted something from it after coaching so many games there over the years.”

There was Doug Wojcik, Taylor remembers, who would throw out baserunners at first base from centerfield, and John Poling, a slow but strong kid who threw flames from the mound and hit 400-foot rockets at the age of 14. Taylor also recalled Ricky Wetzel, who could play any position, and Albert Yeager, a hurler who racked up strikeouts every game he pitched.

And Taylor also coached his three sons, Brian, David, and Gary; two of whom went on to play for American Legion Post 1, and David was a member of the Elm Grove Palomino squad. While each one possessed different talents on the field, the one constant was the rough and tough coach.

“I was tough on all of those boys, not just my three sons, and that was because we were from the Island, and everyone always put the Island down for whatever reason. We had to make those kids tough,” Taylor said. “That’s just the way it was then, and it worked. Our kids were tough, and they were good ballplayers.

“We were the ‘Island Rats.’ You could call us rats, and we wouldn’t care. We were proud of it, and we still are no matter where people may live now,” he said. “If you’re from the Island, you’re a rat and you’re proud of it.”

Porter, now in his mid-40s, played against the Island Tigers and the Island A’s when a Little Leaguer, so that meant he had the chance to visit Belle Isle at last five or six times each summer. When the catcher/outfielder was named an All-Star, it meant playing and practicing there even more.

“Those Island teams I played against had guys like Billy Welker and Gary Taylor on them, and those guys were always great. And the Island teams always had so many more very good players,” Porter recalled. “But we learned the game from people like our fathers and also from ‘Duck’ Dusick and Danny Taylor. They were guys who would show up, drag the field on their own, and offer whatever coaching they could while they were there.

“Guys like that wanted to make sure the kids had great places to play the game because of how much they loved the game,” he said. “Those two, and I’m sure a lot of other people, made Belle Isle Ballpark the place to play for me and everyone else my age, and that’s why I can still remember giving up a home run to Ricky Vargo one time there. That may have been the longest home run I’d ever seen a 12-year-old kid hit,” Porter said. “Ricky is another one of those Island guys who I won’t forget and I was very sad to hear about his passing a few months ago.”

Going … Going … Gone.

As a child growing up in North Wheeling, Porter did not have an elementary school in his neighborhood, and that meant he was assigned to Madison School on Wheeling Island.

“And all of those kids from the Island teams went there, too, so that made baseball season pretty interesting every year,” he said with a laugh. “There were a lot of them who were my best friends, but we were big rivals when it came to baseball. They were my classmates, but there was that edge when spring came, and we all knew we were about to play against each other.

“Looking back at it, it was fun, and during the baseball season the kids from North Wheeling would still ride our bikes across the Fort Henry Bridge so we could play those guys before the games when our parents were there,” Porter recollected. “We would just go over to see if there were the players to play, and we didn’t know because we didn’t have the multimedia we have now, but it usually worked out.”

Once the boys were graduated from Bronco ball, the Island players moved up to Pony League, and that meant playing their games at Bridge Park, a larger complex situated near the public pool and the bridge to Bridgeport, Ohio. The field had a backstop, and the fans could sit in terraced areas along both foul lines, but it was far from the same.

“When my kids had games at the new Belle Isle, I would tell them about how that place used to be, and they didn’t believe me. They didn’t believe there could be a ballpark like that around here,” Porter said. “My kids do know some of the history about the game of baseball here in Wheeling, but they refused to believe that a place like Belle Isle Ballpark ever existed.

“I have heard a lot folks talk fondly about Belle Isle Ballpark since it was torn down,” he continued. “And that’s because taking it down took away that big-time atmosphere that it had. It was a big deal to play there. You felt like you were in ‘The Show” when you played there.”

During the brief debate concerning the facility’s demolition in the early 1990s, Taylor said a few folks expressed concern over security in that area of the north end of Wheeling Island because law enforcement often had to break up nighttime gatherings of teenagers during the summer months and because 40-ounze beer bottles were discovered inside from time to time.

“I was told at one time one of the reasons why it was demolished was because the police couldn’t see inside of it,” he reported. “And yeah, the stadium wasn’t in the greatest shape when it came down. It needed some work, but I know there were plenty of us that were willing to do what we could do if the city was willing to renovate it. But that’s not wait happened.

“And yes, it did get flooded from time to time. If the Island got flooded, that field took on water, too. Sometimes it was worse than other times,” Taylor said. “I mean, the place is on the northern tip of the Island, but really, it was just mud that we and the city had to clean up. Hey, we’re on the Island and whenever that river hit 45 feet, everything over here gets flooded. That’s a fact of life on Wheeling Island and we live with it every day.”

According to city records, Belle Isle Ballpark came down around 1992, according to Tom “Bear” Bechtel, the director of the city’s Recreation Department. Although the exact dates of demolition have blurred in Bechtel’s memory, it is easy for him to recall the internal push to re-invent the facility into yet another aluminum-stands sandlot.

“And it’s the biggest regret I have in my recreation career,” admitted Bechtel, a 43-year veteran of municipal government who has supervised the continued development of the I-470 J.B. Chambers Complex in Elm Grove. “I fought it, but today I wish I would have fought it harder. I hated to see that ballpark come down, and I don’t know if we’ll ever see anything like it again in this city.

“Although I spoke against that demolition every time the subject come up, the powers in place at that time wanted it down. To this day, I can’t tell you exactly why that was, but they wanted it down,” he said. “And you know what? Almost as much money was spent on that demolition as it would have taken to renovate it. That’s the truth, and it makes my stomach turn just thinking about it.”

But she didn’t fall easily, Taylor said.

“The guys who were working on tearing it down said it was more difficult than anyone expected. It didn’t just fall over, and that didn’t surprise anyone on the Island,” he said with an everlasting grudge. “I only watched a couple hours on the first day, and then I had to walk away. It still makes me mad because the place wasn’t falling down. There was nothing falling away from it or hanging from it. It could have been, and should have been fixed.

“The kids were playing ball there before it came down, so it wasn’t like it was a hazard or anything like that. It wasn’t a dangerous place by any stretch, and I don’t care what anyone says,” he insisted. “But that was the decision that was made, and all I told them was that they were making a big mistake, but no one seemed to care what I thought so what happened was this city lost a big piece of our history.”