This is the underground issue of Betty’s Garden Diary. Most of the crops in Betty’s garden have been harvested, but things are still going on. In this installment of Betty’s Garden Diary, we will discuss things that grow from or produce underground parts such as bulbs, tubers, or roots.

A good way to start this underground Garden Diary installment is to dig the potatoes. By the end of August, the foliage on some of our potatoes had dried up, so those potatoes were ready to dig. They were fine in the ground, but we like to dig them before the dried plant tops completely disappear making it difficult to locate the rows. Potatoes are tubers. They grow from stalks called “stolons.” The stolons are stem sections which grow from the main stem of the plant right at ground level. They extend into the soil and expand to form the potato tubers. For this reason, the potatoes from a given plant are located very near to the plant stem, so they are easy to find to dig up as long as that main stem is still visible. We like to use a spading fork. Even though the stolons grow from the plant stem and the potatoes are nearby, we like to start the dig well away from the stem because the potatoes can be several inches away. When you dig your potatoes, try to loosen the soil without crushing or cutting the tubers. After they are dug, allow them to air dry, but do not leave them exposed to the sun for long or they will begin to turn green. If any of the potatoes have green areas on them, be sure to cut those green areas off before cooking them. Before putting the potatoes into storage, keep them in a dry and dark place for a few days to allow any cuts to dry and to cure the them prior to storage. Ideally, the potato bin where you will store your spuds should be in a cool and dark place with a temperature of about 40 degrees. Click here for a PDF document about growing potatoes provided by Michigan State University.

Our sweet potatoes have taken over!

This summer, we also grew some sweet potatoes. Sweet potatoes are actually enlarged sections of the roots of the sweet potato plants. The flesh of sweet potatoes varies in color from very pale or light yellow to deep orange. The darker sweet potatoes tend to have softer flesh and are often sweeter than the lighter fleshed varieties. Many folks insist that the sweet potatoes with the darker flesh are yams. However, true yams are not even botanically related to sweet potatoes. Sweet potatoes are actually more closely related to morning glories! Grocery stores and recipe books sometimes contribute to the confusion by mislabeling dark fleshed sweet potatoes as yams or publishing candied yam recipes that use dark fleshed sweet potatoes. Check out this link if you want to learn more about the differences between sweet potatoes and yams. We started our sweet potatoes from slips that we grew by simply sticking a sweet potato into a bowl of water and allowing it to sprout. We carefully pulled off each sprout and stuck it into wet sand to root. The sprouts rooted quickly and easily, so growing sweet potato slips is a fun activity for kids. This issue of Betty’s Garden Diary was written during the first week in September. Our sweet potato plants were still green and growing at the time that this was written, so we had not yet dug them. We are going to wait to dig the sweet potatoes until the vines die which may be after the first frost. Since sweet potatoes are enlarged sections of the roots, they are sometimes a few feet away from the plant stems. Therefore, we will start digging about three feet from the plant stems using our spading fork. No matter how far away we start digging or how careful we are, we always manage to slice some sweet potatoes whenever we use a shovel! When I till the garden later, it seems like I also manage to till up some sweet potatoes that were missed. Sometimes, those are three feet or more from the plant stems. Even though most of the sweet potatoes will be near where the stem goes into the ground, digging sweet potatoes is like a treasure hunt which is part of the fun. After the sweet potatoes are dug, we will allow them to dry and then store them in a cool and dark part of our basement. Click this link for a good article in the old Farmer’s Almanac about growing sweet potatoes.

Digging Garlic

While we are digging around in the garden, we might unearth some garlic which I neglected to dig when the plant tops died back a few weeks ago and the bulbs were still easy to find. About 35 years ago, an old timer showed Betty and me how to grow garlic. He gave us some tiny garlic bulbs that he had collected from the tops of the stalks on the garlic in his garden. We followed his instructions and planted those in the fall. By the next fall, we had a nice supply of home-grown garlic. Since that time, we have refined our garlic growing somewhat. It turns out that all garlic is not created equal. Garlic experts identify garlic varieties as “softneck” or “stiffneck.” The stiffnecked varieties have a stiff stalk that grows out of the middle of the bulb. That stem is called a “scape” and it is often curled although the variety our neighbor gave us had scapes that grew straight up. The scapes can be cut and eaten early in the summer. Some garlic growing authorities recommend cutting off the scapes to force more energy into the formation of the bulbs. However, one recent study discovered that removing the scapes made very little difference in the size of the bulbs and that one variety of garlic actually produced less when the scapes were removed. We usually leave the scapes alone. If the scapes are allowed to mature, tiny bulbs called bulbils will form at the tops of the scapes. Those bulbils are what the neighbor gave to us to plant years ago. If you are planning to braid your garlic, then you will want to grow one of the softnecked varieties because they do not produce scapes, so they are easier to braid.

Several years ago, I bought two elephant garlic bulbs from a gentleman at the Italian Festival. Instead of eating them, we used the cloves to plant our own row of elephant garlic. Some of our elephant garlic produced bulbs almost four inches in diameter, but we did not care for the flavor, so we stopped growing it. It turns out that elephant garlic is not true garlic. Instead, it is a type of leek. The cloves of elephant garlic are flat and very mild flavored.

If you have not already done so, it is time to dig your garlic. Betty and I neglected ours and the tops were completely gone when we dug it. If you wait too long like we did, then the paper like coating that encases the bulbs tends to deteriorate so that the bulbs come apart when you dig them. That does not impact the taste of the garlic, but it does make braiding the garlic impossible. Even when we dig the garlic on time, we never seem to get it all and the old garlic bed has new growth garlic coming up the next spring. When we dig the garlic, some of the tiny bulbils that grow on the garlic bulbs fall off like kernels of corn, so it replants itself!

This is also the proper time to plant garlic. If you have saved bulbils from the scapes or the bulbs, you can plant those. Otherwise, separate the cloves from a garlic bulb and plant them 2-3 inches deep. A good rule of thumb for all bulb crops including flowers is to plant the bulb at a depth that equals two to three times the height of the bulb. Plant your garlic in a well-drained location with good topsoil and plenty of sunlight and rain. The cloves will start to grow over the winter and the plants will emerge next spring. You can start using the garlic at any time during its growth cycle. If you have never grown garlic, give it a try. It is fun to grow and there is nothing like a little home-grown garlic to spice up your favorite Italian dish and make your house smell nice! This page from the University of Minnesota, provides a lot more information about growing garlic.

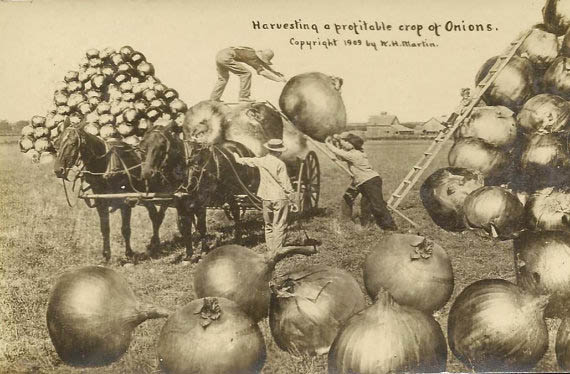

Harvesting onions postcard – circa 1909 (Our onions were slightly smaller!)

We harvested our onions last month by pulling them out of the ground and letting them lay in the garden for a week or so to allow the tops to dry. Around the end of August, we picked them up and removed the outermost skins which were covered with dirt. We braided the small and medium sized ones for storage, but most of the large ones did not have enough of the tops left to support their weight in a braid. Using the process that we described last month, we froze a batch of chopped onions. We realized that many of our onions are used in soups or sauces that also use tomatoes or tomato juice, so we went looking for a canning recipe that included tomatoes and onions. We already have a salsa recipe and we have already canned salsa this summer, but we wanted a recipe that would provide a soup base with only tomato juice, onions and a few bell peppers. We were able to find a stewed tomato recipe that called for tomatoes, onions, peppers, celery, sugar, and salt. Because of the onions, peppers, and celery, this is a low acid recipe which requires pressure canning. We omitted the celery, sugar and salt from the recipe. So our recipe consisted of tomatoes, onions, and bell peppers. Since we had a ton of tomatoes and plenty of peppers, we canned 25 quarts of this for use as a vegetable soup base. The recipe came from the old Ball Blue Book. Even though we removed some of the low acid ingredients when we omitted the celery, we still followed the recommended time for pressure canning this sauce and we will still boil it at least ten minutes after opening the jars before tasting it. We used the largest of the onions for freezing and for the soup base and saved the remainder to store for the winter. We braided some of the smaller ones, but our usual MO for storing onions is to use retired panty hose. We simply cut the legs off of the old hose and then begin filling them with onions. The hose are very strong and they have a lot of stretch. The first onion easily falls into the toe of the hose. We then tie a knot above it and add another onion. We tie a knot above that one and repeat the process until there are a good number of onions in the leg of the hose. Then, we tie a final knot at the top and use a piece of cord to hang the onions in a cool, dry, dark part of our basement to store. To use the onions, just snip off the one at the bottom and work your way up! If you don’t happen to have any retired panty hose at your house, you can also store your onions in old onion bags from the store which is what we did with the ones in the picture below.

Using recycled store onion bags to store some of our onions in the basement.

You might want to try growing some Winter Onions which will be ready to use as green onions next spring. These are also sometimes referred to as multiplier onions or Egyptian walking onions. Winter onions are perennials, so choose a spot that can remain reserved for your winter onion bed for several years. If you want to grow some winter onions, you will need to do a little searching online for the sets or obtain some from a friend. I found winter onion sets online at Burpee Seeds at this address: http://www.burpee.com/vegetables/onions/onion-egyptian-walking-onion-prod002386.html Check out this web site for more information about winter onions AKA Egyptian Walking Onions.

Horseradish

About 35 years ago, we brought a start of horseradish from the farm where I grew up in Ohio to our garden here in West Liberty. We wanted the horseradish leaves to top off the crock of mustard pickles that we were planning to make using Uncle Everett Heimberger’s recipe. We have continued to grow that horseradish for the last 35 years! Horseradish is a perennial so it comes up every year. I think it will grow just about anywhere except in a swamp. It seems to thrive on neglect and once you get it started it just keeps on going. To get it started, obtain a chunk of the root from a friend or other source, dig a hole and throw it in the ground. That is about all it takes, but the proper approach is to loosen the soil to a depth of about a foot and mix in a little compost. Then plant the root section at about a 45 degree angle so that the top will be a couple of inches below the soil surface after it is covered. Let it grow the first year without harvesting any of the roots. After that, harvest all you want.

Horseradish that we dug from the iris bed. I put my size 12 in the photo to show the size of the root.

We even dug up the whole plant that we had in the iris bed along Rt. 88 last month and it still came back from the small roots that we missed. Our primary motivation for digging the horseradish clump in the iris bed was to remove it from the bed and to take some photos for this article. Even though we tried to get it all, it still came back, so it is pretty resilient! We use the horseradish leaves for our mustard pickles and seldom harvest the roots. However, I grated some of the roots from the horseradish that we dug from the iris bed last month and tasted it to see if it tasted like grocery store grated horseradish. It was the real McCoy, but it had way more kick than any store-bought horseradish! By the way, a compound called Allyl Isothiocyanate provides the heat in horseradish. Allyl Isothiocyanate is also responsible for the heat in mustard. The heat in hot peppers is caused by a different compound called capsaicin. If you want to grow horseradish for the roots, check out this page from the Mother Earth News.

Daffodil Bulbs from the clump that we dug

Outside the vegetable garden, some underground things worth mentioning are going on in our flower beds. This is the time of the year to lift, divide, and replant flower bulbs. For us, that means daffodils. Daffodils are sometimes also called “Narcissus” or “Jonquils.” From a botanical standpoint, the terms “Narcissus” and “Daffodil” are interchangeable. However, “Jonquil” actually refers to a specific variety of daffodils. The flower bed along route 88 in front of our house consists of daffodils planted between bearded irises. Since we discussed dividing the irises last month, we won’t do so again, but we have dug some of the daffodils this year to fill in empty spaces in the beds. The daffodils were spectacular this spring, but they have long since completed their growth for this summer and the leaves and stems are completely gone now. Back when they were blooming, Betty used small stakes to mark the locations of the clumps that we wanted to divide so that we would be able to find them when the time came to dig and divide them. We used our spading fork to loosen the soil around the clump of bulbs that we wanted to divide so we don’t crush them when we lift them out of the ground. All of the bulbs in the picture came from that one clump of daffodils which had never previously been divided.

Plant plenty of bulbs We improved the heavy clay soil in this bed by adding some compost.

Daffodils like loose well drained slightly acid soil with a pH of 6.5 to 7, but they seem to be able to tolerate a variety of soil conditions. In addition to the daffodils in the flower bed in front of our house along Rt. 88, we have a bed containing a couple of hundred daffodils below our garden. Those daffodils are growing in poor soil with a high clay content. Inspired by the daffodils on the hillside near Bethany College, we also planted daffodils on a bank on our lot along Harvey Road. All of them bloomed this spring providing proof that daffodils are easy to please. If you are going to plant daffodils in a new bed, start by loosening the soil to a depth of about eight inches or so. If you are planting a lot of daffodils in the bed, the easiest option is to remove the top five to six inches of soil and mix it with a little compost. Then, arrange the bulbs and put the topsoil back covering the bulbs so that the bases of the bulbs are five to six inches deep. Plant lots of bulbs in the bed so that the daffodils will produce plenty of blossoms the next spring! When we took the picture above, we were replanting a bare spot in our daffodil bed where the ditch for a sewer line had destroyed the flowers. The backfill in the ditch was rock filled clay subsoil, so we used the spading fork to loosen it and added compost. We covered the bulbs with a topsoil-compost mix taken from a different location. Remember the rule of thumb for bulbs that the base of the bulb should be at a depth equal to three times the height of the bulb. That puts the top of the bulb at a depth below the soil surface that is equal to twice the height of the bulbs. If you are planting less daffodils, then you might opt to use a bulb planter. Bulb planters come in two styles. One style looks a little like a spade with places for you to step on it with your foot to push it into the ground thereby removing a plug of soil. Then, you drop the bulb into the hole making sure it lands right side up and simply replace the plug of dirt. The second type of bulb planter has a handle for your hand which you use to twist it into the ground to remove the plug of soil.. If you are going to plant lots of flower bulbs, you will want to save your wrists by investing in the spade type of bulb planter! We planted the daffodils on our hillsides using a bulb planter and they have done very well.

Bulb Planters

This is also the time of year to plant other flowering bulbs including tulips, crocuses, grape hyacinth, and allium. We have yellow and purple crocuses. The yellow crocuses always signal the coming of spring by blooming the earliest followed by the purple crocuses a few weeks later. No matter which fall bulbs you decide to plant, just follow the same procedure as we described for planting daffodils and remember the rule of thumb that the bottom of the bulb should be at a depth that equals three times the height of the bulb or the top of the bulb should be twice the height of the bulb below the soil surface. Check out this web site from the University of Illinois for more information about planting and caring for flowers that grow from fall bulbs.

The old clump of peonies in the historic West Liberty Cemetery

During the spring of 1985, Betty and I and our kids were working on cleaning up the old West Liberty Cemetery which was badly overgrown at the time. As I was about to mow down a clump of weeds, Betty stopped me and informed me that the clump of weeds was actually a clump of peonies. Betty’s father grew lots of peonies on the farm where she was raised, so she recognized them immediately. Betty and I continued to mow around those peonies when we took care of the cemetery until a few years ago when the town of West Liberty took over the mowing and the town maintenance workers have followed suit. Every summer, those peonies bloom. I think that peonies thrive on neglect.

Peony Root – Note the white buds near the top of the root.

This is the time of year to plant peonies. If you have an old clump of peonies that you want to move or divide, now is the time to do so. If you are planting peonies for the first time, choose the location carefully because peonies do not like to be moved. Peonies like fertile well drained soil and a full day of sunshine although they will still produce some blooms if they get at least half of a day of sun. Make sure to stay well away from trees because peonies require plenty of water which the tree roots would pull out of the soil. If you are dividing an established clump of peonies, expect to do some work to get them out of the ground because the roots are very tough and woody. Normally, peony clumps are not divided until they have been growing undisturbed for several years, so the roots can be somewhat large. Divide the roots into good sized sections. Remove any dead or damaged roots. Prepare a good sized planting hole by loosening the soil with a shovel or spading fork to a depth of eight to ten inches. While you are preparing the soil, mix in some compost and then replace some of the soil and gently tamp it down, being careful to not compact it, so that the tops of the peony roots will end up only about one to two inches below the soil surface. Place the peony roots on the tamped soil with the eyes facing upwards and then backfill the soil over the top of them pressing it down gently but firmly. If the soil is very dry, water the peonies well. They don’t like saturated soil, so you will likely only need to water them once unless the weather stays extremely dry. If so, then water them thoroughly every couple of weeks to help them to root. The best advice for growing peonies is to leave them alone! Most of the time, they do not need any extra fertilizer and you do not want to cover them with heavy mulch. When they bloom, you might want to use stakes to hold up the blooms. Peony blooms are quite large and heavy, so they usually end up on the ground especially after they get soaked with rain. Don’t expect too many blooms from them during the first couple of years because peonies take three or four years to become well established. This is a link to an Old Farmer’s Almanac web page about growing peonies and this link connects to a Clemson University web page about growing peonies.

Yellow Jackets

Since this issue of Betty’s Garden Diary is all about underground things and we are in the late summer, it would not be complete without discussing yellow jackets. Yellow jackets are members of the wasp family. They look a little like hornets or even honeybees, and they often build their nests in old ground mole burrows. Even though they often live in the ground, yellow jackets do not dig burrows. They just take over what is already there. They will also gladly build their nests in hollow spaces in the foundation of your home or in a piece of pipe laying on the ground or anywhere else that suits the purpose. A few years ago, our granddaughter was stung several times by yellow jackets which had built a nest inside the walls of her outdoor plastic sand box. At this time of year yellow jacket nests are usually quite large and very active. When they are disturbed, yellow jackets are extremely aggressive and whoever disturbed them usually receives multiple stings. Unfortunately, we don’t usually notice the in-ground yellow jacket nest until we run over it with a lawnmower or otherwise disturb it and end up getting stung. Fortunately, nests that are in the ground are fairly easy to exterminate. Over the years, we have used several different insecticides to successfully kill in-ground nests of yellow jackets. My usual MO for eliminating in-ground yellow jacket nests is to duct tape a coffee can onto a long piece of wood and then pour about a pint of insecticide solution into the hole at night. I use a lot of the solution because the nest may be several feet from the opening. That usually eliminates the living yellow jackets, but more hatch out within a few days, so I also dust the hole thoroughly with Sevin dust the next day. Most of the local garden centers sell insecticides that will kill yellow jackets. If the nest is left alone, the cold winter weather will kill off the entire colony except for the fertilized queen which overwinters and looks for a place to establish a new colony the following spring.

Betty and I hope that you are enjoying the Betty’s Garden Diary series. Since we started this series in December a year ago, our year will soon be up. There will be only two more Betty’s Garden Diary installments. The October installment will concentrate on soil testing, so we are planning to publish it around the beginning of October to provide folks with enough time to have their soil tested before the weather turns bad. As part of the November issue, we will reflect on the year and on some of the things that we will plan to change in our garden for next summer. Please add your comments and suggestions to make this a community effort. – Earl