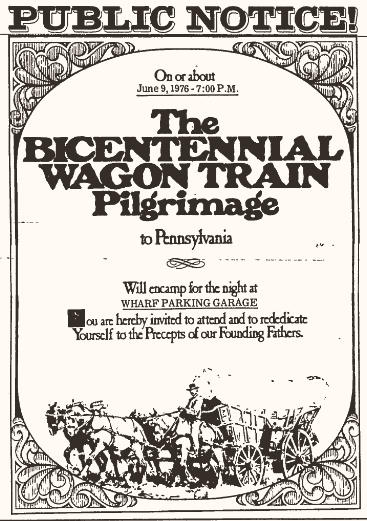

Almost 50 years ago, in 1976, an unlikely sight appeared on the Ohio River at Wheeling—a barge carrying an old-fashioned wagon train! Hundreds of people traveling by Conestoga wagon and dressed in pioneer garb spent the night of June 9, 1976 docked next to the Wheeling Wharf Parking Garage – what we now know as Heritage Port.

But why? It certainly was not the first time Wheeling had seen a wagon—the city’s location on the Ohio River and along National Road made it a prime destination or pass through for travelers heading west. The onset of the 20th century and growth of other transportation options, however, made wagons very unusual over the past century. This wagon train was passing through Wheeling on its way to a birthday party…for the United States of America.

The Bicentennial Wagon Train

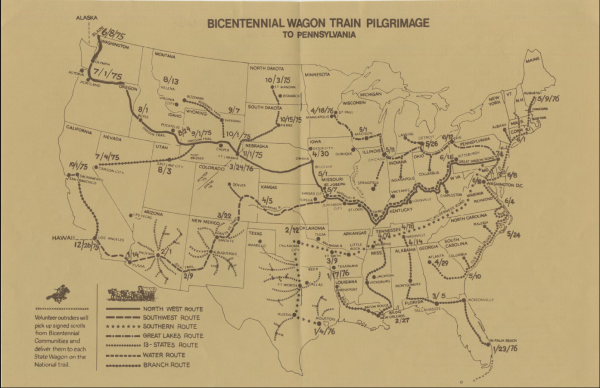

The Bicentennial Wagon Train Pilgrimage was a reenactment of white American settlers’ journeys west—mostly during the 19th century. The journey, however, was done in reverse—the wagons started on the west coast during the summer of 1975 and traveled east for about a year. Including an official wagon for every state, up to seven wagon trains traversed across the various historic routes—eventually meeting up in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania for Bicentennial celebrations on July 4, 1976. Supported by the federal American Revolution Bicentennial Administration, it was an official project of the Bicentennial Commission of Pennsylvania.1

Like many Bicentennial-related projects in the 1970s, the wagon train meant different things to the vast variety of people that make up America. Inspired by the popular narratives of westward expansion, the initiative was supposed to inspire patriotism and a national refocus on American history in anticipation of the 200th anniversary of the United States’ founding. For many, the reenactment provided entertainment, connection to a national project, and historical excitement. For others, such as Native American tribes, the Bicentennial and its related activities were not celebrations but rather indicative of the displacement of their people and loss of traditional lands. While many Americans flocked to see the wagon train roll through their town, some—like members of the Stillaguamish Tribe from Washington—protested and blockaded the path.2

The pilgrimage attempted to follow the trails, turnpikes, and roads that pioneers traversed originally. According to the Washington Post, the train made 249 official encampments—complete with festivities and performances by an entourage from Pennsylvania State University—in addition to many other informal stops.3 As the journey progressed through the country, independent wagons and riders joined along—the group swelled from a couple hundred participants to over a thousand.

Along the way, the wagon masters collected “Rededication Scrolls”—signatures from Americans recommitting their dedication to America’s principles of freedom. By the time the wagon train reached Valley Forge, it had collected signatures from approximately 22 million people (about 10 percent of the nation’s population). One of the final people to sign a scroll was President Gerald R. Ford—right before he signed a bill making Valley Forge a national historical park.

An Overnight in Wheeling

During the 19th century, Wheeling was an important link west. It was a crucial port city on the Ohio River and, for a few years, it was the terminus of National Road (the first major highway built by the federal government). Wheeling provided an opportunity for pioneers to get resources, supplies, and respite before a long journey west—either by wagon or barge/river boat along the Ohio River. During the same year as the wagon train (1976), the American Society of Civil Engineers designated the National Road as a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark.4 The Bicentennial Wagon Train’s official souvenir program (sold along its journey) specifically mentions Wheeling several times in its history of wagon roads and westward expansion.

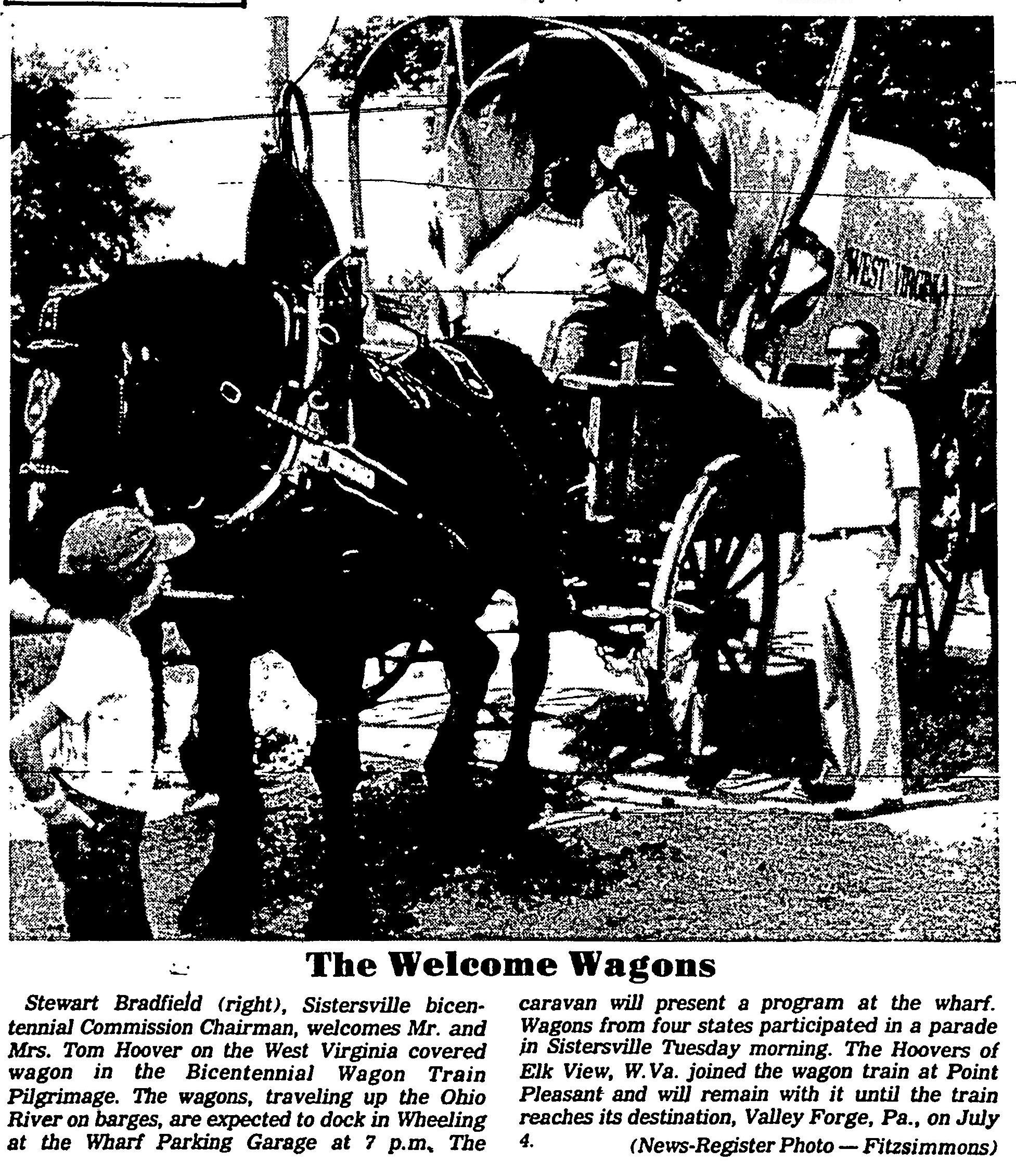

Even though there was no official encampment planned for Wheeling, the Bicentennial Wagon Train docked overnight next to the Wharf Parking Garage. A barge had pulled the wagon train north on the Ohio River from an official event in Sistersville, WV. Wheeling’s newspapers, The Intelligencer and The Wheeling News-Register, wrote about the unusual sight and even interviewed participants on the wagon train about how their journey was going. While it was in town, the vice-mayor of Wheeling, William Muegge, presented the wagon master with scrolls signed by the people of Wheeling.5

When’s America’s Next Birthday?

As we look back on the commemoration, events, and moments of America’s Bicentennial, it is already time to look to the upcoming Semiquincentennial—the United States’ 250th birthday in 2026! It might seem early, but many states have already enacted commissions—including the West Virginia Semiquincentennial Commission—across the country to plan for the anniversary’s various commemorations, programming, and events.

Part of the purpose of the Bicentennial Wagon Train was to reflect on how different life had become in the two hundred years since 1776—from clothing to food to the size and diversity of the United States—and what it means to be an American. As we consider the next big anniversary, communities are going to have to consider how to continue to create an America that lives up to its founding ideals. Printed in a Wheeling newspaper in 1976, one participant described the wagon train as “an American dream”—but was it reflective of all Americans’ dreams?

How do you think the country, state, and community should commemorate the 250th anniversary of America’s founding?

• Emma Wiley, originally from Falls Church, Virginia, was a former AmeriCorps member with Wheeling Heritage. Emma has a B.A. in history from Vassar College and is passionate about connecting communities, history, and social justice.

References

1 Bicentennial Wagon Train Pilgrimage to Pennsylvania, 1975-1976, Harrisburg, PA: The Bicentennial Commission of Pennsylvania (1976), Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library & Museum, accessed September 3, 2023, https://www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov/library/exhibits/bicentennial/038900000-004.pdf.

2 M.J. Rymsza-Pawlowska, Public History and Popular Culture in the 1970s, (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2017): 134.

3 Monica Hesse, “Bicentennial Wagon Train signatures are lost pieces of American past,” The Washington Post, July 3, 2011, accessed Sept. 3, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/bicentennial-wagon-train-signatures-are-lost-pieces-of-american-past/2011/06/30/AGo7zxwH_story.html.

4 “National Road,” American Society of Civil Engineers, accessed Sept. 3, 2023, https://www.asce.org/about-civil-engineering/history-and-heritage/historic-landmarks/national-road.

5 “Scrolls Presented,” The Intelligencer, June 10, 1976, p. 21, accessed Sept. 3, 2023, http://ohiocountywv.advantage-preservation.com/viewer/?k=%22wagon%20train%22&i=f&by=1976&bdd=1970&bm=6&bd=10&d=06101976-06101976&m=between&ord=k1&fn=the_intelligencer_usa_west_virginia_wheeling_19760610_english_21&df=1&dt=3.

6 Mike Myer, “Wagon Train Is American Dream to Participant,” The Intelligencer, June 9, 1976, p. 15, accessed Sept. 3, 2023, http://ohiocountywv.advantage-preservation.com/viewer/?k=%22wagon%20train%22&i=f&by=1976&bdd=1970&bm=6&bd=9&d=06091976-06091976&m=between&ord=k1&fn=the_intelligencer_usa_west_virginia_wheeling_19760609_english_15&df=1&dt=5.