The local Wheeling branch of the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) is well-known around the city for its services and impact on people’s lives. However, for over three decades between 1921 and 1956, Wheeling’s YWCA was segregated. The Blue Triangle Branch was the African American YWCA and served as an important center of the Black Wheeling community.

Origins of the YWCA

The Young Women’s Christian Association was started back in 1855 in England and looked very different from what it is today. It was originally focused on creating a support system with educational, housing, and religious assistance for young women moving into cities.1 Over the past 166 years, it has morphed into a worldwide organization that works in local communities in over a hundred countries with millions of different people. Wheeling’s YWCA was started in April 1906 and moved around a few locations before settling into a newly constructed building at 1100 Chapline Street, where it currently resides.2

Today, the YWCA has grown far past its original intentions and is the “oldest and largest multicultural women’s organization in the world.”3 The current mission of the YWCA USA is “to eliminate racism, empower women and promote peace, justice, freedom and dignity for all.”4

History of the Blue Triangle

The YWCA, as a national organization, was never formally segregated and has long had racial equality as an integral part of its mission and work. However, there were local chapters that decided to segregate, often by communities of Black women who decided to form their own branches, like the Blue Triangle Branch of Wheeling.

During the 20th century, Wheeling was a racially segregated city with its own set of Jim Crow rules—to read more about the history of segregation in Wheeling, click here. To more fully support the Black community—specifically Black women and girls—members of the Wheeling YWCA and other active community members created the Blue Triangle Branch in 1921.

While Wheeling had one of the most prominent African American branches of the YWCA, it was not the first. In 1889, the first African American YWCA branch was started in Dayton, Ohio.5 However, the Blue Triangle’s activities were often reported in both local and national newspapers—including the Baltimore Afro-American and the Pittsburgh Courier, two of the largest Black newspapers in the country during the 20th century.6

The work that the Blue Triangle undertook during its 35 years could fill an entire book, but it was all related to the goals of empowering women and improving the community. The Blue Triangle and its work was led by a variety of Black women—young, old, married, unmarried, employed, unemployed, mothers, daughters, aunts, and grandmothers.

The Blue Triangle hosted numerous classes for women to learn life skills like typing, shorthand, sewing, and dressmaking, but also more fun activities like art, dancing, and bridge. There were summer camps for children, leadership training for adults, job placements for the unemployed, and partnerships with local organizations to run public health programs like infant health clinics. The Blue Triangle worked closely to foster relationships with churches in the area and the Lincoln School, the Black public school at the time.7

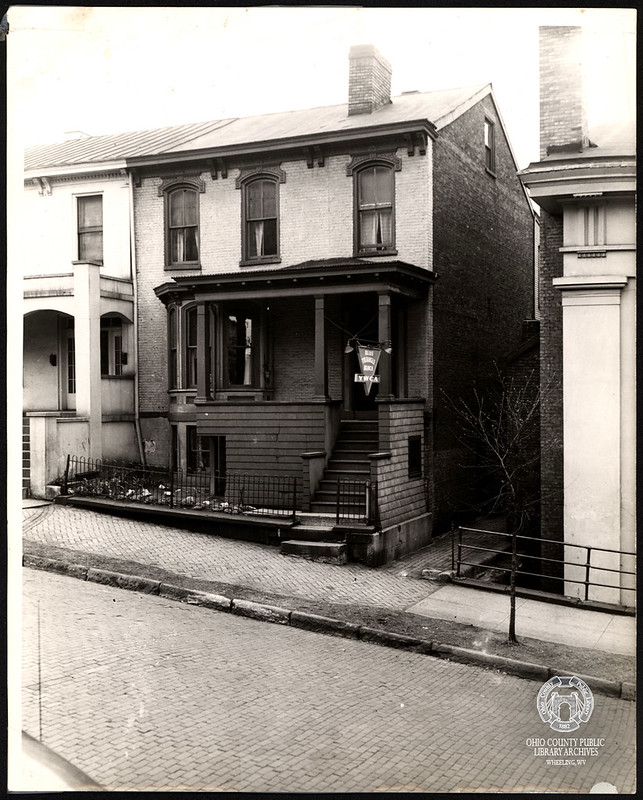

While Wheeling’s central YWCA had its building at 1100 Chapline Street, the Blue Triangle moved up and down the street from 1041 to 1035 Chapline, before finding its final, most recognizable home at 108 12th Street in 1943.8 Although it no longer belongs to the YWCA and has undergone structural modifications, the house still exists. In addition to official Blue Triangle business, the building itself was used as a meeting place for numerous other community organizations and clubs.

An important aspect of the Blue Triangle and the YWCA, in general, was its residential program for women to stay if they didn’t have other safe places to go. The Blue Triangle hosted both permanent and temporary visitors and was listed in The Green Book for Black travelers.9 One of the Blue Triangle’s most prolific committees was its Inter-racial Committee that worked to encourage interracial cooperation in Wheeling and advocated for racial equality and civil rights across the country. One of their recurring programs was “Race Relations Sunday,” which was a partnership with local churches to encourage conversations about racial equality.

Even though all of its programming was an essential part of the organization, the Blue Triangle’s mere existence as a place of community, aid, and safety was crucial to a segregated Wheeling.

Reintegration

While YWCA chapters, especially in the South, were segregated, the YWCA recognized racial equality as an early goal, integrating their national meetings, conferences, and activities much sooner than many other organizations. In the 1930s, YWCA members and chapters were encouraged to raise awareness about mob violence and lynching. YWCA conferences were interracial, which occasionally required explicit notice to attendees that they would be welcome at the hosting establishment, no matter their skin color. The YWCA’s Interracial Charter was adopted in 1946, declaring that “wherever there is injustice on the basis of race, whether in the community, the nation, or the world, our protest must be clear and our labor for its removal, vigorous and steady.”10

The 1954 US Supreme Court decision, Brown v. Board of Education, ruled that racial segregation of public schools was unconstitutional.11 While it took a long time for school desegregation to be implemented in a lot of places, several Black Wheeling students began to filter into the previously all-white schools. In 1956, Lincoln School, the Black public school, closed.12

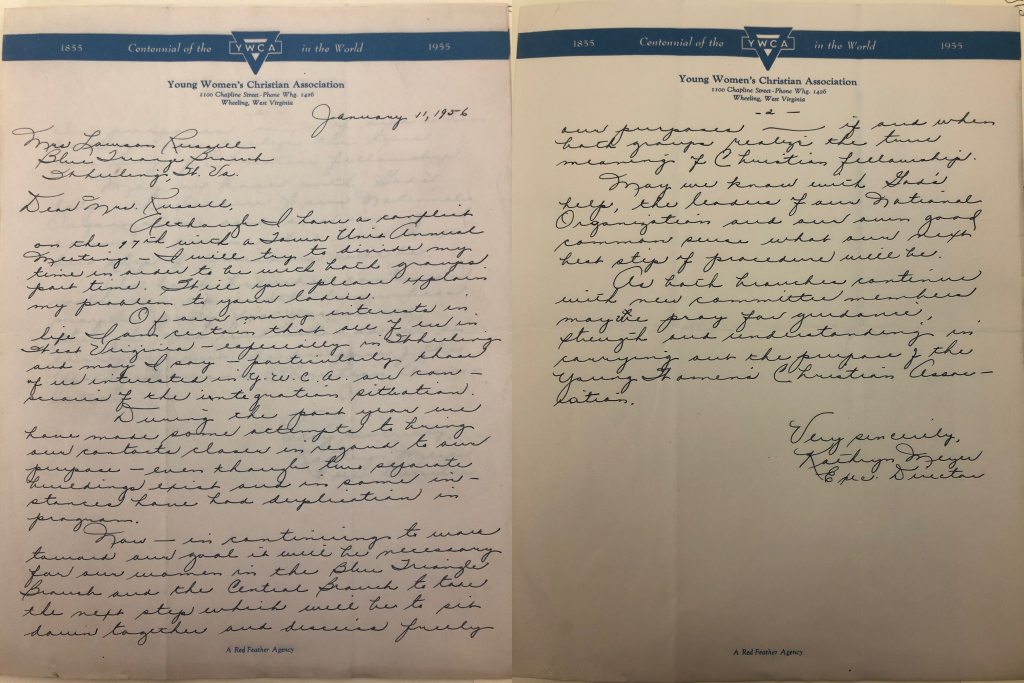

It was in this atmosphere of school desegregation and the start of the Civil Rights Movement that conversations started about desegregating the Wheeling YWCA. In addition, many of the segregated YWCA branches across the country were starting to reintegrate.13 The leaders in Wheeling decided that they would be more effective at helping the community working as one unit, so the Blue Triangle reintegrated with Wheeling’s central YWCA in June 1956.

To this day, the impact of the Blue Triangle Branch lives on in the fond memories of the empowering programs it ran, the community it created, and the continued work of the YWCA.

To learn more and access primary sources about the YWCA Blue Triangle Branch, please contact the Ohio County Public Library Archives here or check out their online finding aids, here.

• Emma Wiley, originally from Falls Church, Virginia, was a former AmeriCorps member with Wheeling Heritage. Emma has a B.A. in history from Vassar College and is passionate about connecting communities, history, and social justice.