Editor’s Note: This article was originally published on Nov. 6, 2020. In commemoration of Black History Month, Weelunk continues to share stories that explore African American history, stories, and narratives in Wheeling and West Virginia. We felt this story on The Green Book was especially timely to share, as the Ohio County Public Library is set to host a special program featuring Alvin Hall, author of Driving the Green Book on Tuesday, February 20 at noon. You can learn more about this program here. We will continue to share new articles by and about Black history and African American contributions throughout February and beyond. If you have suggestions for content you’d like to see on our platform, we encourage you to submit them at weelunk.com/submit-idea/.

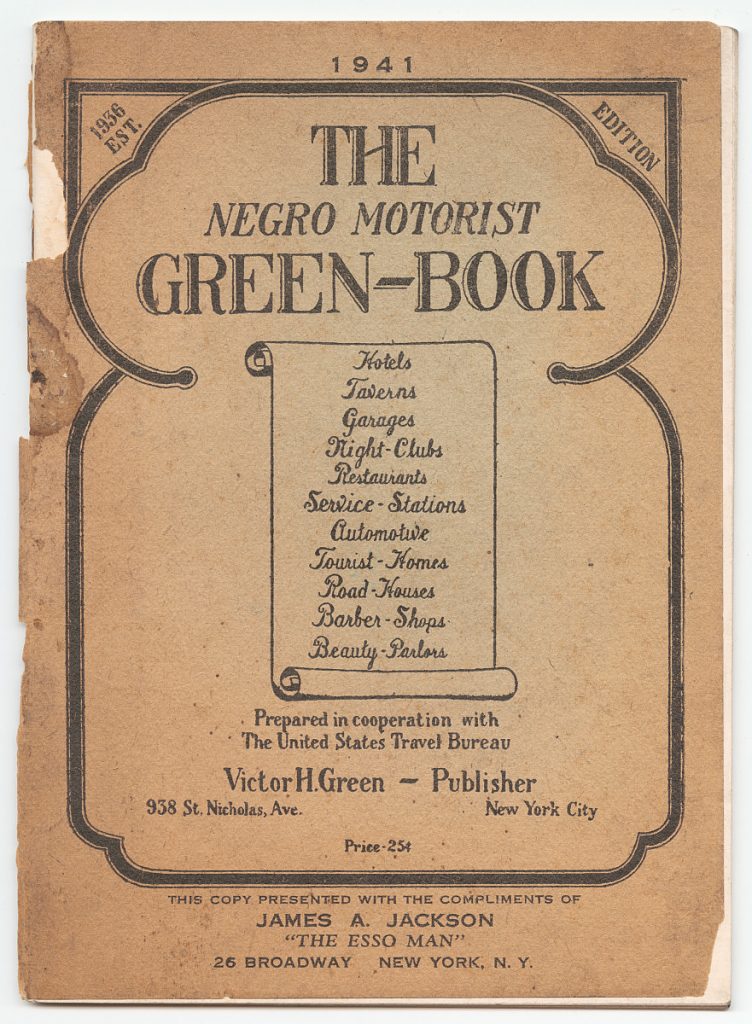

“Write for Reservations—Moderate Rates.”1 This 1956 listing for lodging at the Wheeling Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) Blue Triangle Branch did not just reach a local audience; in fact, it was part of a book that was distributed and used across the entire nation. The Negro Motorist Green Book, or simply, “The Green Book,” was a travel guide, published from 1936 to 1966, that catered to Black travelers in the U.S. The creator and publisher, Victor Hugo Green, a Black mailman in Harlem, saw the need for a publication that African Americans could reference when on the road, looking for a hotel, restaurant, gas station, and more. The Green Book has garnered attention over the past few years with its portrayal in popular culture, including most notably, the 2018 award-winning film, Green Book.

In the time of racial segregation during the first half of the twentieth century, traveling in unfamiliar places created dangerous situations for Black travelers and tourists. While “Jim Crow” laws mandated legalized segregation—including in Wheeling—many locales also instituted forms of “de jure” segregation, which historian John David Smith describes as “segregation by custom, habit, or practice.”2 If unaccustomed to the practices and “rules” of a particular place, African Americans could experience anything from the discomfort and humiliation of being refused service to threats and physical harm. Even though Wheeling was the location of the Wheeling Convention, where the northwestern counties of Virginia refused to secede before the Civil War, the city still became segregated. On the blog, Archiving Wheeling, which is run by the Ohio County Public Library, historian Seán Duffy writes that “whether by code or custom, for African American people in Wheeling, Jim Crow meant separate everything—from restaurants and movie theaters to beauty parlors and hotels.”3

As a Black mail carrier, Green used his own knowledge and the experiences of other postal workers to compile a list of Black-friendly establishments in New York City for the first Green Book edition in 1936. The guide quickly expanded to include other towns and cities across the country; Wheeling first appeared in 1939. While many people mailed in recommendations to fill out The Green Book, one of the largest groups of contributors continued to be local Black mail carriers, whose routes allowed them to experience and gather intel on which businesses were hospitable to African Americans.

Throughout the twenty-one years that Wheeling existed in The Green Book (1939-60), there were six lodging options, three beauty parlors, two restaurants, two night clubs, and one drug store. There were changes to the establishments—over the years, one or two would be added, a few would disappear. Only one place was included in every edition Wheeling is in: Mrs. W. Turner’s Tourist Home at 114 12th Street. “Mrs. W. Turner’s” was most likely run by Elizabeth “Lizzie” Turner, wife of William “Bill” Turner, the first Black policeman in Wheeling. Even before The Green Book’s creation, census records show evidence of “roomers” living at the Turner residence.4 Since Elizabeth died in 1957 but the tourist home is still listed until 1960, the business was probably continued by her daughter, Minnie Turner Shannon, or grandson, Oliver Shannon, both of whom had lived with Elizabeth.5

Even though many, if not all, of these places no longer exist in Wheeling, connections still surface in the records of local and oral history, if you know what you are looking for. For example, the only Wheeling pharmacy that is ever listed in The Green Book (1950-55), Northside Pharmacy on Chapline St., was run by James S. “Doc” White. “Doc” White can be found in the Wheeling Hall of Fame, an honor bestowed by the City Council, and his pharmacy is remembered as “a safe gathering place for generations of African American young people.”6

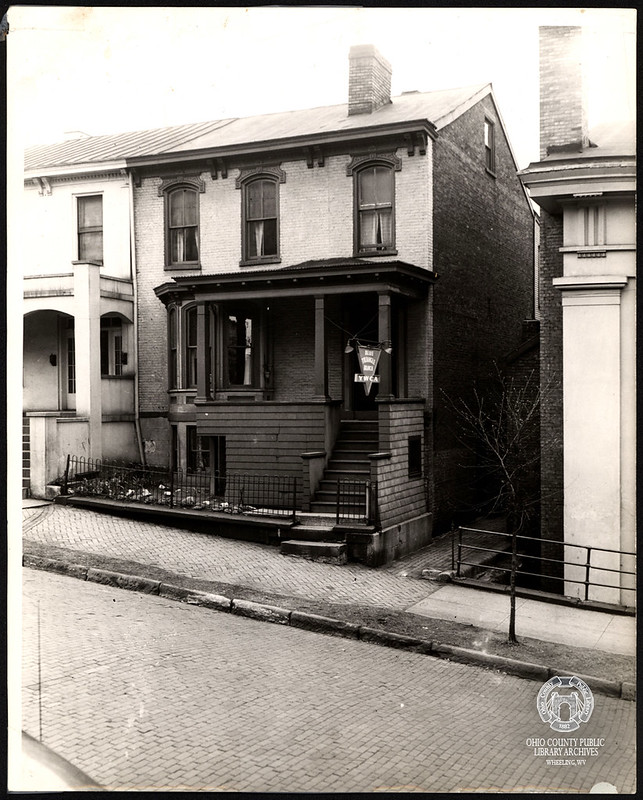

Even though The Green Book was supposed to alleviate harmful effects of racial discrimination, it can also reveal more about the segregated state of Wheeling at the time. From 1949 to 1956, the Blue Triangle Branch of the YWCA was listed in The Green Book as a place to find lodging. Even though a chapter of the YWCA was founded in Wheeling in 1906, from 1921 to 1956, the YWCA was segregated into two chapters.7 As displayed by The Green Book, African Americans were only welcome at the Blue Triangle Branch, whose history is relatively well-documented in the Ohio County Public Library Archive. Ron Scott Jr., who is currently the Program Director of Cultural Diversity & Community Outreach at the YWCA, explains that when it “decided to segregate it was more of an act of service than obeying the law of the land. They didn’t have to establish the Blue Triangle. They saw a need and took a stance. I feel honored to continue the fight to eliminate racism and empower women.” Today, the current Wheeling YWCA’s listed mission is to “eliminate racism, empower women and promote peace, justice, freedom and dignity for all.”8

Not only did The Green Book provide security, guidance, and peace-of-mind for Black travelers, it also increased the visibility and advertisement of Black-owned and operated businesses. According to the Smithsonian African Diaspora curator, Joanne Hyppolite, The Green Book sheds more light on the “entrepreneurship of black women.”9 In Wheeling, most of the listed businesses were presumably run by Black women. These include several tourist homes in addition to Mrs. W. Turner’s, such as Mrs. C. Early at 132 12th St., Mrs. R. Williams at 1007 Chapline St., and Mrs. J. T. Hughes at 1021 Eoff St. Beauty parlors such as Miss Hall’s and Miss Taylor’s, both on Chapline Street, were also promoted using female, specifically unmarried, names.

While a little over a dozen Black-friendly establishments were officially published in The Green Book, there were presumably other additional unlisted places that African Americans passing through Wheeling could find accommodation. Ron Scott Jr. remembers his grandmother, Ethel Stradwick, hosting the famous singer/songwriter, James Brown, when he was performing nearby. It was not a formal arrangement—Ethel did not run a boarding house or hotel—Brown was just not allowed to stay at the hotels in town and he had a fondness for her caramel cake.

In the mid-1950s, the listings for Wheeling in The Green Book started to diminish until it vanished from the Book altogether by 1961. Many, if not all, of these establishments no longer exist in Wheeling—their owners have passed on and several of their buildings no longer stand. For many of these businesses that were so crucial to a Black traveler’s sense of security and autonomy, The Green Book is one of the only accessible records that documents their existence.

In the 1948 edition, about halfway through The Green Book’s period of existence, Victor Green predicted that “there will be a day in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States.”10 The Green Book ceased its publication in 1967, three years after the seminal Civil Rights Act of 1964 made it illegal for businesses to discriminate and refuse service on the basis of race, color, sex, religion, or nationality.11 Today, The Green Book is thankfully no longer needed to direct Black travelers to safe locations in Wheeling, but it does acknowledge the struggles and documents the businesses and establishments that paved the way.

Special thanks to Ron Scott Jr. for his help and conversation. If you have any stories, information, or history about any of Wheeling’s Green Book locations, please contact Emma Wiley by email at ewiley9@gmail.com.

• Emma Wiley, originally from Falls Church, Virginia, was a former AmeriCorps member with Wheeling Heritage. Emma has a B.A. in history from Vassar College and is passionate about connecting communities, history, and social justice.

References

1 Victor Hugo Green, The Negro Motorist Green Book: 1956, (New York: Victor H. Green & Co. Publishers), Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library Digital Collections, accessed September 4, 2020, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/9c454830-83b9-0132-d56a-58d385a7b928.

2 John David Smith, When Did Southern Segregation Begin?, (Boston, New York: Bedford, St. Martin’s, 2002), 7.

3 Seán Duffy, “Wheeling’s 20th Man: 250 Years of Race Relations in the Northernmost Southern City of the Southernmost Northern State.” Archiving Wheeling, June 23, 2020, accessed September 9, 2020, http://www.archivingwheeling.org/blog/wheelings-20th-man-250-years-of-race-relations-in-the-northernmost-southern-city-of-the-southernmost-northern-state.

4 U.S. Census Bureau. Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930. FamilySearch, accessed September 15, 2020, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9RZN-SVB?i=2&cc=1810731&personaUrl=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AXMHR-3X6.

5 U.S. Census Bureau. Sixteenth Census of the United States: 1940. FamilySearch, accessed September 14, 2020. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-89M1-YQFF?i=27&personaUrl=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AK7ZF-BW4.

6 Seán Duffy, “Wheeling’s 20th Man: 250 Years of Race Relations in the Northernmost Southern City of the Southernmost Northern State.”

7 “YWCA In Wheeling,” Ohio County Public Library, accessed September 14, 2020, https://www.ohiocountylibrary.org/history/4051.

8 “About the YWCA Wheeling,” YWCA Wheeling, August 13, 2019, accessed September 8, 2020, http://ywcawheeling.org/about/.

9 Jacinda Townsend, “How the Green Book Helped African American Tourists Navigate a Segregated Nation,” Smithsonian Magazine, April 2016, accessed September 4, 2020, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/history-green-book-african-american-travelers-180958506/.

10 Victor Hugo Green, The Negro Motorist Green Book: 1948, (New York: Victor H. Green & Co. Publishers), 1, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library Digital Collections, accessed September 4, 2020, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/6fa574f0-893f-0132-1035-58d385a7bbd0#/?uuid=6fc25440-893f-0132-9aa2-58d385a7bbd0.

11 Civil Rights Act of 1964, 88th Congress, Public Law 88-352, U.S. Statutes at Large 78 (1964): 241, accessed September 14, 2020, https://www.eeoc.gov/statutes/title-vii-civil-rights-act-1964.