Steve Bliss Can Relate to the Recent Hostage Crisis in Iran

He was captured, bound, and blindfolded, and he drank nothing and ate very little during the days he was held hostage by the Iranian military.

Two or three days, well, Steve Bliss isn’t sure exactly.

What he does know is that it was the end of third month in the Middle East, he was an active specialist with the United States Army National Guard, and he was taken. Riding on one of two speed boats, very similar to what we see on the Ohio River during the area’s warmer months, Bliss found himself and three other battle buddies surrounded by boats and ships of the Iranian Navy.

Those three and Bliss were captured. Iran claimed the two speed boats that were seized were full of spies because they floated into its territorial waters. Bliss cannot tell you that it’s not true, either. Fact is, he and comrades were serving as escorts to private contractors, and they found themselves surrounded by military crafts equipped with 50-caliber kill machines.

And they were taken. Held hostage.

So, when the news broke this past week about 10 American sailors being captured for allegedly floating into Iranian waters, it floored Bliss. The reports triggered a funk, but then it provoked his patriotism. He commented on the situation with status updates on his Facebook Timeline.

“Hey everyone, just received news that ten sailors have been captured by Iran. Please, please please please, find another believer or more and pray for these 10 sailors for their release!!!”

And then, “Let’s make a deal, send me back to Iran in exchange for 10 sailors!!!”

“It brought it back,” the 36-year-old Bliss said. “I’m not going to lie. That news took me back to that room because people here just don’t understand. In that situation, you have no idea what’s going to happen. No idea whatsoever.”

Doing His Duty

Bliss was raised by his grandparents initially in Shadyside, Ohio, and then he lived with them in West Liberty. After graduating from Wheeling Park High School in 1998, he attended West Liberty University, but he then decided to move in with an aunt in Gainesville, Fla.. At first, he wanted to attend the University of Florida, but when he was unable to gain any scholarship dollars, he opted to join the National Guard on June 26, 2001.

Bliss then requested and was granted a transfer to the Moundsville Guard unit following the tragedies that unfolded on Sept. 11, 2001. In March 2003, he was deployed to Fort Bragg, N.C., and then was dispatched to Kuwait as a member of 12 Bravo Combat Engineers. Bliss quickly learned that his duties involved providing security for a private contractor, KBR Inc., a global technology, engineering, procurement and construction company serving the hydrocarbons and government services industries.

On May 30, 2003, he and three battle buddies found themselves surrounded.

“Every day we provided security for KBR people, and we took them out of Kuwait and into Iraq, and one day we had a water mission between Iraq and Iran,” Bliss explained. “We had to take the people from KBR to pick some Iraqi workers, and we were in civilian speedboats and not military vessels. First we went to an oil platform, and then in between Iraq and Iran we got ambushed, blindfolded, and interrogated.

“I don’t know where we were at the time. I don’t know whose waters we were in,” he admitted. “I didn’t see the GPS, and I don’t think it was accurate anyway, but it seemed like we were going the right way. Everything was fine until that happened.”

The Iranian military had deployed several boats and ships to apprehend the Americans, and it was obvious the soldiers were angry and very serious.

“I could literally feel the sweat running down the crack of my ass. I thought that was it. Twice my life flashed in front of me. At the time when we were captured, I literally saw my body floating in the water,” he said. “The second time happened after they had taken us inland as we were blindfolded. I really thought we were going to be lined up and have our heads cut off.

“I was 22 years old and an E-4 in the Guard, and I was thinking that I had a good life,” Bliss said. “We had heard a lot of stories about what could happen to us if we ever were captured, and we had been told about the name-rank-serial-number thing, and that’s what I was prepared to do. But I believed I would die because of it.”

All four Americans were accused of being spies, and a few of Bliss’ belongings did not help his pleas of innocence.

“No one spoke English to us until the third day, or maybe it was the second day. It’s still very unclear to me, but it was definitely longer than a day and some,” Bliss explained. “I do know that when they were taking us one-by-one to interrogate us there was a guy behind me with a pistol, and another guy got real close to me. Like right between my legs. And he asked, ‘Why you Americans in Iranian waters?’

“They were saying that we were spies, and it kind of got a little rough because they wanted more than our name, rank, and serial number. They wanted more information than what I was offering, but all I told them was that I was a hometown boy form the Ohio Valley.” He recalled. “I told them that we were the security and picking up those Iraqis, but because I had a camera with me and a recording device that I could use to email voice messages to my girlfriend (Amy) at the time, they determined that I was a spy.”

Most of the time he lay on a dirt floor pretending to be asleep, but on occasion the U.S. soldiers were taken to a room, alone, and the Iranian interrogators demanded answers to very curious questions.

“I could hear their weapons, and I could hear them sharpening of knives,” Bliss said. “One of the KBR guys started telling them that they could not hold him because he was an American civilian. They took him out of the room, and I don’t know what happened to that guy.

“They kept asking why we were in those waters and if I was a spy, and then they asked why Iraq,” he continued. “One of the guys kept asking me, ‘Why Bush? Why Bush?’ And another one of them asked me, ‘You know Madonna?’ I told him that no, I didn’t know Madonna.

“There came a point to where I could lift my blindfold while I pretended to sleep because when they had us inland and inside this room with a dirt floor, our hands weren’t bound,” he added. “They tied our hands when they took us there, but then they let my hands free when they got us into that room.”

The Iranians then demanded an admission from the soldiers.

“What they wanted us to do was sign on the dotted line. They wanted us to admit we were spies,” Bliss said. “I wouldn’t sign it. I was just a kid from the Ohio Valley. I wasn’t a spy. If I signed that piece of paper, I thought I would be signing, literally, my life away.

“But I ended up signing it because they told me my friend had signed, so there came the point where I chose to give it to God. I signed,” he said. “That’s when they tried to feed me, but I wouldn’t eat anything because I thought they would urinate or defecate in the food. I wouldn’t eat at all.

“And then on the second or third day, I’m not sure, they interviewed us without our blindfolds. They had a camera set up, and I had to say that I was fine and that I was being taken care of. And they had watermelon. And yeah, I had three pieces of that because I was starving at that point. I don’t remember having anything to drink the whole time, but I did eat those pieces of watermelon.”

But then he was tossed back into the room with his comrades. He was still a prisoner despite following the abductors’ orders.

“At one point I saw myself, 20 years later, saying, ‘I’m your dad’ to my son,’” Bliss said. “It was so crazy. I was reacting to every little sound. There were hours and hours and hours and hours. I think it made me nuts a little bit, and my mind was traveling in every direction.

“On the third day one guy took me downstairs, and he took my blindfold off. He looked like he was 14 years old, but he told me that I could use the restroom. Before leaving, I asked if I could wash my face, and there was a window with bars over it. When I looked out that window I saw our two speedboats, so that’s when I was thinking about killing that guy and taking off.

“But that’s when I thought about the other three guys, and there was no way I was leaving them. I wanted us to get out together if we were going to get out of that situation.”

Freedom

He doesn’t know what time it was. The sun was out, though, and without notice Bliss and the other three American combat engineers were moved on June 1, 2003.

“They moved us to one of their boats, and then onto our boats, and then they told us to sail away. Then we got to the USS Chinook, and we boarded that ship,” he recalled. “They gave us the satellite phone to use so we could call our families. It was an emotional time, but our families didn’t really know what was going on.

“Word got out because some of the other guys we were serving with told their wives and girlfriends, and they told them that we were missing,” Bliss said. “The only time I saw anything on TV was after I got back to the naval base in Kuwait. And then our people started asking a lot of questions about the whole ordeal.”

Bliss and the others were debriefed, and they spent close to a week with their unit before the Defense Department ordered them to American soil. Following counseling sessions in Washington, D.C., he was permitted to return to West Virginia, where he was honored by then-Gov. Bob Wise in Charleston.

“During that press conference there was a guy from CNN,” Bliss recalled. “That reporter asked me, ‘How do you feel?’ I looked right at him and said, ‘I don’t even know you, and I’m glad to see you.’

“Then I got to come home and my son, Spencer, was born on the day Saddam Hussein was captured (Dec. 13, 2003),” he said. “And then my daughter was born on the anniversary of when I was captured. I took that as a sign.”

Bliss also was given the opportunity to meet President George W. Bush before a rally staged at Wesbanco Arena on Aug. 29, 2004.

“I remember trying to be all professional when meeting him, but when he gave me a hug his earlobe went into my mouth. Literally,” Bliss said. “That was after being in Washington, D.C., for counseling because all four of us were having some problems.

“All I know is that I wanted to get home to be with my family,” he said. “That was my only goal once we got out of there. I just wanted to be back with my family.”

Anything concerning Iran provokes his recollections, and the sounds of a soccer game do, too, because while he was held hostage, the abductors were watching the sport on a nearby television. Bliss also has been diagnosed with post traumatic stress disorder.

“That experience does bother me because when we had the sailors captured this week, I got very emotional for them,” Bliss admitted. “When I heard about it, it took me right back into that situation. I remembered losing hope. I gained it, and I lost it. I gained it, and I lost it. I remembered how much of a roller coaster it was.

“I don’t think about it every day, but I have done speeches about it on Veteran’s Day and other days. During my counseling, I was encouraged to talk about it, so when I do those speeches it really helps me with it,” he continued. “I’ve talked to churches and the Boy Scouts, and I enjoy it because I’m telling a true story. It did happen to me.”

Bliss was notified on Thursday he was being promoted to an E-6 staff sergeant, and he is assigned to the same unit. He is also a member of the state’s National Guard Honor Guard and often travels throughout West Virginia to honor veterans who have passed away.

“I love doing what I get to do for the funerals of our veterans. It’s very patriotic,” Bliss said. “I am the regional coordinator of the West Virginia Army National Guard Honor Guard and I’ve traveled as far as Martinsburg. It’s something I get to do a few days of every week, usually.

“We no longer do many for World War II veterans, but Korea and Viet Nam we honor most of the time,” he continued. “And I will do it for as long as I can because our veterans deserve it, and I love being a part of it.”

Bliss also feels blessed because of his relationship with Jim Forbes, former news anchor for WTRF TV 7 here in Wheeling who now serves as the communications director for U.S. Representative Mike Bost.

“I saw him one day at T.J.’s, and I told him I thought he was great on the news. And then we got to talking about a lot of different things. We got into a deep conversation,” Bliss said. “I eventually told him that I never really had a dad in my life, and that’s when he said. ‘I’ll be your dad.’ I took that very seriously, and I thought we could see where it goes.

“He’s a man with integrity and looks me in the eye, and he cares. He wants to see me grow, and he doesn’t walk away when I fail,” he continued. “Lisa, his wife, is a wonderful person, too, and we have remained very close and will forever.”

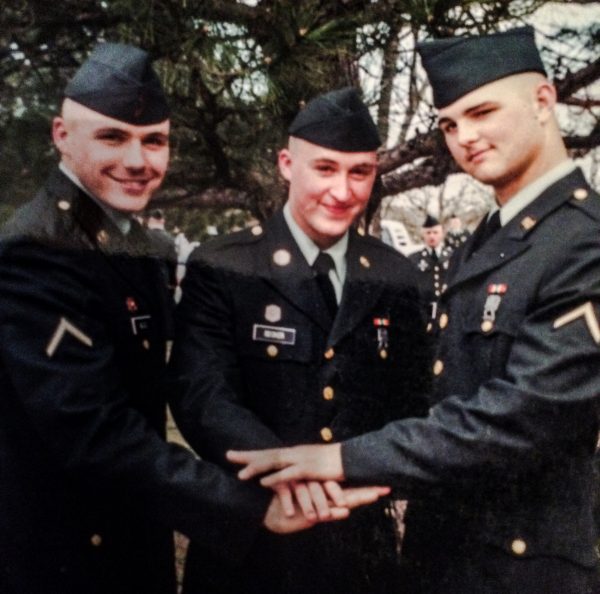

(Photos provided by Steve Bliss)