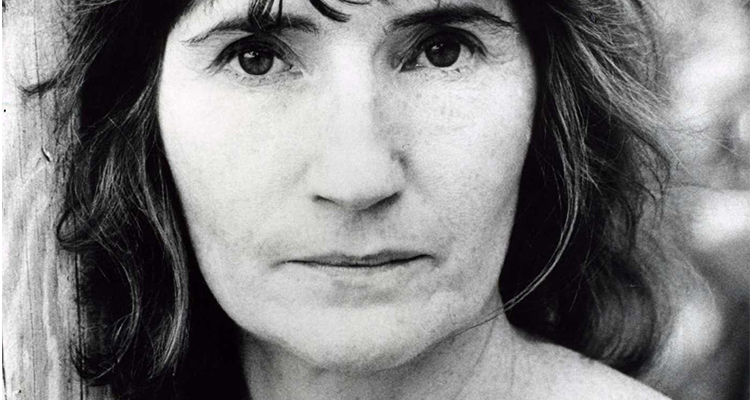

First up at noon Tuesday, Aug. 27, Lunch With Books will pay tribute to the late Hazel Dickens, who Smithsonian Folkways Magazine called, “One of the most important bluegrass singers of the last 50 years.”

WHY HAZEL DICKENS?

WHY HAZEL DICKENS?

Born in coal country in Montcalm, West Virginia, in 1935, Hazel Dickens was the daughter of a preacher and a musician. Her eldest brother, Thurman, along with two brothers-in-law, coal miners all, died of black lung disease during the era when coal companies still denied the existence of the disease.

At age 16, Hazel, along with some of her 11 siblings, left West Virginia to join the post-war Appalachian migration to eastern cities for work in the factories of Baltimore. There Hazel met musicians like Mike Seeger, Bobby Baker and Alice Gerrard, who teamed up with Hazel to become the first women to front a bluegrass band. In the 1960s, Hazel began writing and singing about labor issues with songs like “Black Lung” (a tribute to her brother) and “The Mannington Mine Disaster,” in honor of the 78 miners trapped and killed in the Nov. 20, 1968, explosion in a coal mine north of Farmington and Mannington, West Virginia.

Hazel’s powerful voice was featured in the film Harlan County U.S.A. She also appeared and sang in the films Matewan and Songcatcher. She was inducted into the West Virginia Music Hall of Fame in 2007. Despite living in Washington, D.C., most of her life, Hazel’s heart was always in West Virginia, as reflected in her anthem, “West Virginia My Home.” Hazel Dickens died in 2011.

THE TRIBUTE

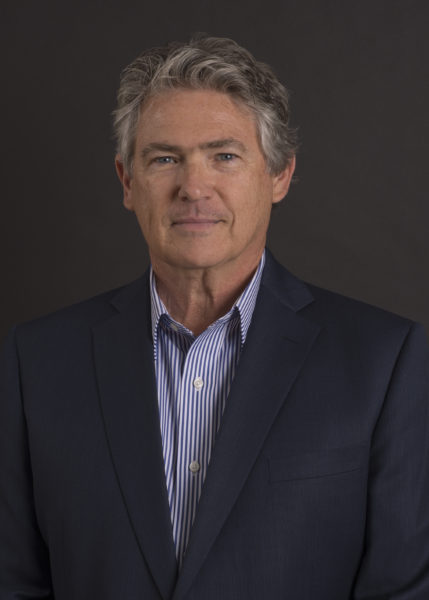

Radford Virginia University history professor Dr. Richard Straw, a scholar of American roots music who interviewed Hazel Dickens at the home of Mike Seeger in 1994, will discuss her life and career.

At regular intervals during Straw’s talk, country singer Karen Collins, backed on mandolin by her husband, Fred Feinstein, will perform several of Hazel’s classic songs, including “Black Lung,” “They’ll Never Keep Us Down,” “The Mannington Mine Disaster,” “Working Girl Blues” and “West Virginia My Home.” According to her website: “Karen writes exceptional songs that she delivers in a traditional style — Hazel Dickens meets Loretta Lynn.”

A genuine “coal miner’s daughter” herself, Collins lives today in the Washington, D.C., area, where she performs with the honky-tonk band “The Backroads Band,” the Cajun band “Squeeze Bayou,” and the acoustic country quartet “The Blue Moon Cowgirls.” She also teaches at the Augusta Heritage Workshops in Elkins, West Virginia.

KAREN & HAZEL

Like many country and bluegrass singers, Karen adores Hazel Dickens, who once told Karen, “You look like I did when I was young.”

In fact, there are many connections between Karen and Hazel, starting with Abbs Valley, Virginia, where Karen grew up.

“Recently when I was talking to Arnold Dickens, Hazel’s nephew,” Karen said, “he told me that at some point Hazel and her family had lived in Abbs Valley up School House Holler, which was not far down the road from our house. Hazel must have been young when they lived there, and our times of being there wouldn’t have overlapped. But I still thought it was pretty cool to find out that Hazel had lived Abbs Valley, too.”

Karen later had a few memorable personal encounters with Hazel. “Several years back, John Lilly, a friend from Charleston, West Virginia, played a house concert at our house, and I opened for him. Hazel came to the concert, and I was feeling kind of intimidated to be singing in front of one of my heroes, but she was so sweet and encouraging. She stayed around after the concert hanging out and talking. That’s when she told me that I looked like her when she was younger. I thought that was a great compliment.”

“The last time I saw Hazel was in December before she died. I was part of a tribute show to Hazel that she attended, and I was also her driver that night. I was glad to get to spend some time with her by myself. Driving back to her house in Georgetown, we talked about the show, about West Virginia and about singers that we liked. We planned to go out to lunch when the weather got warmer (she didn’t like to be out in the cold weather), but unfortunately, I didn’t get to see her again.”

Karen’s love of music began early. “I’ve always l wanted to be a singer/musician. I loved singing in our local Baptist Church. When I was growing up, my family wasn’t particularly musical, but we listened to music on the radio a lot. I got a late start as a songwriter, around 2005 … I was taking singing lessons because I wanted to learn how to yodel, and my voice teacher gave me an assignment to write a song … So I took the challenge and wrote my first song, ‘Tail Light Blues.’ I liked it (the song became the title cut for my first CD with my honky-tonk band, Karen Collins & The Backroads Band), and I have continued to write songs since then.”

In addition to Hazel, Karen counts Merle Haggard, Harland Howard, Loretta Lynn and Hank Williams among her favorite performers. “My two favorite Hazel songs are ‘Lost Patterns’ and ‘Mama’s Hand,’” she said.

Karen was born in a small community called Skygusty in McDowell County, West Virginia, and grew up nearby.

“Then we moved to the other side of the mountain to another small mining community, Abbs Valley, Virginia. My daddy continued to work in the mines in McDowell County for 30 years, so he drove over that mountain and back every workday. Many of Daddy’s relatives lived in Skygusty, and we spent a lot of time there. I love those West Virginia mountains, and it breaks my heart to see what mountain top removal has done to them. The mountain that Daddy drove across to get to work is totally gone, blasted away. I wrote a song about it. It also breaks my heart to see that much of the area in and around where I grew up is a struggling, depressed area with a lot of poverty and health problems.”

Recently, Karen performed in the rotunda of the Hart Senate building in D.C. “There were over 120 retired coal miners with Black Lung, widows of miners and their families,” she said. “Many of them were in wheelchairs, and many carried oxygen with them. They had come up from West Virginia, Virginia and Kentucky to advocate for their miner benefits. I sang Hazel’s ‘Black Lung,’ and it was the most moving musical experience I’ve ever had.”

Karen has never been to Wheeling. “We never ventured that far north when I was growing up,” she explained. She is looking forward to her visit.

ELAINE PURKEY — MUSIC AND SOLIDARITY

The Dickens tribute will be followed a few days later — at 7 p.m. Friday, Aug. 30, at the First State Capitol, 1413 Eoff St. in Wheeling — with a live performance by singer and activist Elaine Purkey. The show is presented by the WALS Foundation, through its Reuther-Wheeling Library & Labor History Archive, in partnership with the Ohio County Public Library.

A songwriter and union activist from Harts Creek, West Virginia, in Lincoln County, Purkey wrote songs for the Pittston Coal Strike and Ravenswood Lockout. Since then, she has performed nationwide at various festivals, concerts and rallies.

“One Day More,” a song she wrote for the Ravenswood Lockout, is featured on the Smithsonian Folkways Recordings compilation “Classic Labor Songs.” Purkey is portrayed in the 2014 film “Moving Mountains,” based on a book by Penny Loeb. She currently teaches children’s singing classes at the Big Ugly Community Center.

Elaine’s husband, Bethel, will be accompanying her to Wheeling. He was one of the leaders in Logan during the Pittston Strike of the 1980s, and he was asked to help the locked-out Ravenswood Aluminum workers. He was instrumental in helping to pull off the Moss 3 Prep Plant takeover during the Pittston Strike, which became the turning point.

“I know some of the people will enjoy talking to him,” said Elaine, “especially some of the men who might have been around during those days. He is a third-generation coal miner and is the reason I became involved in the labor movement.

“I can never, ever remember a time when I didn’t love music,” said Purkey. “I started singing in public for large family gatherings when I was just 5 years old. The Pittston Coal Miners in Logan County needed someone to represent them in song, and I was known in the area because I had been performing on ‘The Friendly Neighbor Show’ radio program, and they asked me. I agreed, but the songs I researched did not fit anything that we were going through at the time, so, I started writing my own.”

Elaine became interested in writing and singing about union causes because of a man named Rick Wilson. “He is not a big name in music, but he is the one person who pushed me to write and pushed me to sing the songs I’d written. Rick taught me ‘Union,’ and that made the biggest change in my way of thinking. The biggest influence in music overall is God first, and my dad and mom next. Daddy was a musician, and Mommy was a singer. There was always singing at our house growing up. Ours was the local Saturday Night Jamboree House all the years I was growing up.

MEMORIES OF HAZEL DICKENS — LET ‘ER FLY!

Asked to describe Hazel Dickens’ music, Elaine proclaims, “Prolific! Perfect! She knew how to put words and music together to get a point across. She told me once that I had that same quality. I told her not like her, and there is no comparison in my book. She said, ‘But the difference in my songs and yours is that yours give people hope that it will be better in the future and mine all have one foot in the grave.’

“We would talk for hours every time one of us would call the other. We mostly talked union, singing, performing, writing and laughing at ourselves over the things that had happened to us because of our backwood, honest attitude about things when we first got started. Of course, she became a legend, but I got married and had a family, which kept me from going where I could have furthered my music. We talked about family and cooking, and she gave me her scratch recipe for baked beans one time.

“We were together several times and talked a lot on the phone. We sang in jams together, and it was funny because both of us have to sing lead all the time, and we both absolutely love harmony, and we would kind of exchange quips back and forth about who would sing lead and who would sing the harmony. Do you wanna guess who won that argument? Lol. She would just say, ‘I’m older. I’ve been at this longer than you, and you’ll have time after I’m gone, so I’m singing the harmony this time.’ We’d both laugh, and I would say, ‘But if you’re gone — I won’t have anybody to sing after.’ ‘Oh, you’ll find somebody,’ she’d say. But you know — I haven’t yet! We never thought we sounded alike, though. I said it was the style that made people hear that. She said we both sing in that let ‘er fly style. We just stand up, rare back and let ‘er fly!”

Elaine thinks music has always been important to the labor movement. “It says something that sends a message to people — to all people, and many people will listen to a message in a song when they won’t listen to it in a speech. People can sing their message as they march or while standing in a group. But, I guess most of all, it brings people together. Music is universal. When my CD was released, it went to a place called Astonia. The DJ that did a review of it after he played it on his radio program said what he thought of it and said that people were really liking it a lot — he said they didn’t understand the words but they understood the message by the way I sang the words. He said the most requested song from the CD was ‘America! Our Union.’ He said that people could understand the message and talked about it when they requested it and told him how it moved them just to hear it being sung. I think that’s powerful. Don’t you?

“Now, given the way Hazel wrote and sang and the emphasis she displayed throughout her songs, don’t you think they understood her message also? All the older labor/struggle song singers had that ability to purposefully accent with emotion like that in their music, whether it was on stage, on a recording or on a picket line to draw people in. Sometimes, when I’m on stage, and I want audience participation, I let them know that, and if I don’t get much response from them, I stop right in the middle of a line and say, ‘Now, come on, my little pre-schoolers can do better than that, and they don’t know half the words. Now let’s try that again.’ The whole attitude of the crowd changes after that. People will stop and listen to a message being sung when they won’t to words being said in a speech. That’s power!”

Asked about West Virginia, Elaine said, “I love the people and sense of community of my state. It breaks my heart to see it torn apart by extractive industry and politics.”

She has been to Wheeling once before, during the Ravenswood Lock Out. “I traveled up there with the Local 5668 Steelworkers’ Band and sang at a rally … I think [your] language and lifestyle is more Pennsylvanian than West Virginia. However, we have the same thing going on in the Eastern Panhandle also. It changes when you get to Charleston, and it starts to really change a great deal when you get to Morgantown. There’s a reason why we have the nickname of Little Switzerland — not just because of the weather.”

She has a request for her Wheeling audience.

“Please, keep an open mind when you listen to me talk because I might say something that sounds like one thing, and it means entirely something else. We have our own way of talking down here in the belly of this state, and it’s different than up North. And I live three miles up a holler (hollow) where I was born and raised, and we have our own way of expression. I love everybody in this state and if we differ on some issues and levels of understanding, then talk to me about it. I guarantee you, I mean nothing evil or mean about what I say. Except maybe if I’m talking about ‘the filthy rich’! Lol.”

• Seán Duffy is adult programming director at the Ohio County Public Library and the executive director of the Wheeling Academy of Law and Science (WALS) Foundation, both in Wheeling. He has a law degree from the American University and has written books and articles about Wheeling’s history, particularly focusing on immigration. He is editor of the Upper Ohio Valley Historical Review.