Did you know you can pitch story ideas to us? One reader recently sent us a note about a topic that their family had been pondering:

“My family was having a discussion about where the term ‘Charley horse’ came from. A quick google search turned up this HuffPost article. According to the article, one theory is that the phrase originated with Jack Glasscock and there’s a section [in the article] quoting the Wheeling Intelligencer.”

-Curtis W.

Thanks, Curtis! Yes, it looks like this phrase may have a Wheeling connection after all. It’s believed that the name “Charley Horse” was applied to the condition of cramping legs sometime in the late 1800s. Since then, its specific origins have eluded journalists, linguists and everyday folks alike.

After taking a look at the article submitted by the reader, as well as a few other sources, it’s clear that no single person can take credit for coining this colorful phrase.[1,2] Instead, I’ve grouped the various rumors and heresy into a few groups. At the end, you can decide for yourself which theory you think is most credible.

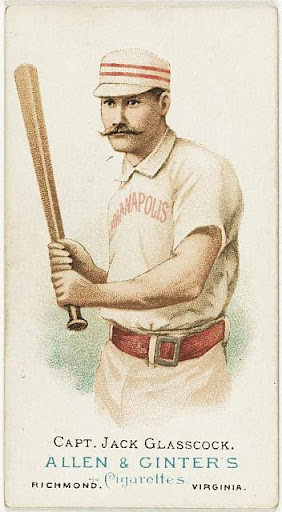

Hometown Hero: The Glasscock Theory

“Pebbly Jack” Glasscock—so-called this because of his habit of picking up and tossing pebbles while in the outfield, is Wheeling’s connection to this dialectic oddity. [3] Born in Wheeling in 1859, Glasscock began his professional baseball career in 1879 and is regarded as one of the best shortstops in history.

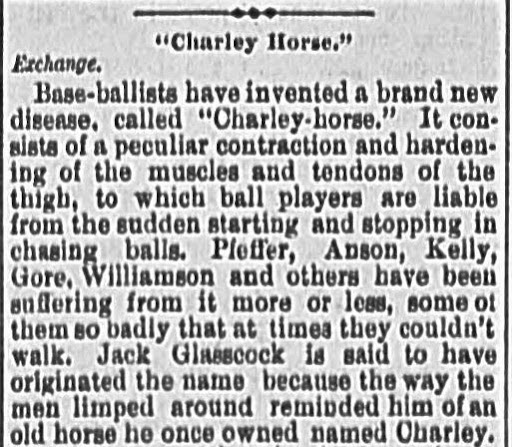

An 1886 blurb in the Wheeling Intelligencer credits him with coining the phrase, because “the way the men limped around reminded him of an old horse one once had named Charley.” [4]

Another Jack-adjacent origin theory is that his father, Thomas Glasscock, compared his son’s limping to their old horse named Charley. But as we’ll see later, the “Old Horse” theory has enough lore to be considered its own category.

A Day at the Races: Other Baseball Players and Horse Racing

Reports about who coined the phrase “Charley Horse” circulated about other baseball players of the time. Joe Quest, Hugh Nicol, Charles “the Hoss” Radbourn, even the baseball-evangelist Billy Sunday have been linked to a horsey tale or two. Most of the stories are similar to Jack Glassock’s – man has leg cramps during practice, man walks funny, someone comments on it.

READ MORE: The Giant Wheeling Tabernacle Built in Only Four Days

Instead of teasing each tale out, I’ve grouped them together here because of my Wheeling bias (Team Pebbly Jack all the way – only HE could come up with such a weird phrase). I’ve also put them in their own group because a few of the stories also deal with another popular pastime of the 1880s: horse racing.

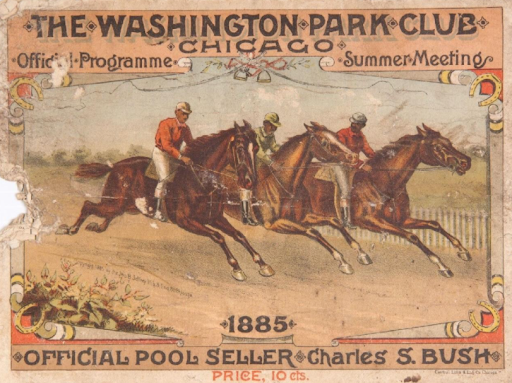

One account places baseball players at the Washington Park Race Track in Chicago, Illinois, on their off day during the 1886 season. A player’s hot tip on a horse named Charley inspired some last-ditch betting by the players. Unfortunately, their horse did not perform as expected. The next day in practice one of the players was limping around with the tell-tale affliction and his teammates hollered after with some variation of “you’re looking like that ol’ Charley Horse!” [5] So much for team spirit, huh?

My thought was to see if there was even a racehorse named Charley. Luckily, David Shulman, author of the article “Whence ‘Charley Horse’?” Already looked into this when he conducted his research on the phrase in 1949. Shulman determined that horses named Champagne Charlie and Charley Hogan did run races in 1886, so that may be the grain of truth needed to bolster the credibility of this theory. [6]

Charley, The Horse

Lastly, what if there was just an old horse named Charley? As mentioned before, Jack Glasscock’s father is said to have compared his limping son to their old workhorse, Charley. Joe Quest’s father is also rumored to have said a similar thing to his son referring to a horse at their machine shop. [7]

Alternatively, it was said that Charley was just an old horse that hauled equipment at the Chicago White Stocking’s ballpark.[8] In other stories, he pulled a dust brush to even out the terrain on the baseball diamond. Either way, this older draft had a distinctive gait that the ballplayers would evoke when teasing one another.

Now that I’ve laid out some of the possibilities to you, what do you think about the origin of the phrase “Charley Horse”? Does the great Jack Glassock deserve all of the credit? Should we honor the hardworking Charley the horse? Or maybe there’s another theory that I’ve overlooked. Perhaps we’ll never know… but as an exercise in curiosity, I’d like to hear what origin story you favor, dear reader. Whatever you choose, let this be a reminder to stretch and stay hydrated before engaging in physical activity, lest you become intimately acquainted with the Charley Horse.

• Kate Wietor is currently studying Architectural History and Historic Preservation at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia. She spent one glorious year in Wheeling serving as the 2021-22 AmeriCorps member at Wheeling Heritage. Since moving back to Virginia, she’s still looking for an antique store that rivals Sibs.

References

[1] Caroline Bologna, “Why Is It Called A ‘Charley Horse’? | HuffPost Life.” August 9, 2019. Accessed December 6, 2021. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/charley-horse-origin-name_l_5d4b3e44e4b01e44e4749142.

[2] Emily Petsko, “Why Do We Call a Leg Cramp a Charley Horse? | Mental Floss.” October 19, 2018. Accessed December 6, 2021. https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/559913/why-do-we-call-leg-cramp-charley-horse.

[3] WVPB. “May 1, 1879: Jack Glasscock Makes Major League Debut,” May 1, 2019. https://www.wvpublic.org/radio/2019-05-01/may-1-1879-jack-glasscock-makes-major-league-debut.istory Classroom,” The History Teacher 11, no. 1 (1977): 29-30.

[4] The Wheeling Intelligencer, July 23, 1886

[5] Bologna, 2019

[6] Shulman, David. “Whence ‘Charley Horse’?” American Speech 24, no. 2 (1949): 100–104. https://doi.org/10.2307/486616.

[7] Bologna, 2019

[8] Shulman